Part II of a post discussing facial fractures. This post specifically discusses fractures of the frontal bone and orbit.

Facial Fractures: Midface and Mandible

Part I of a post discussing facial fractures. This post specifically discusses fractures of the midface and mandible.

Accidental Tracheostomy Decannulation

Written by: Chezlyn Patton, MD (NUEM ‘27) Edited by: Keara Kilbane, MD (NUEM ‘25)

Expert Commentary by: Matt McCauley, MD (NUEM ‘21)

Introduction

Tracheostomy is a common procedure in the US with over 110,000 trachs placed annually (1). Complications occur at a rate of approximately 40-50%, however most complications are minor, with only 1% being catastrophic (1). Of these devastating complications, 90% occur within the first 10 days of placement. Overall approximately 15% of tracheostomies will be decannulated accidentally, and in a critical care setting, 50% of airway related deaths were associated with accidental tracheostomy decannulation (1, 2).

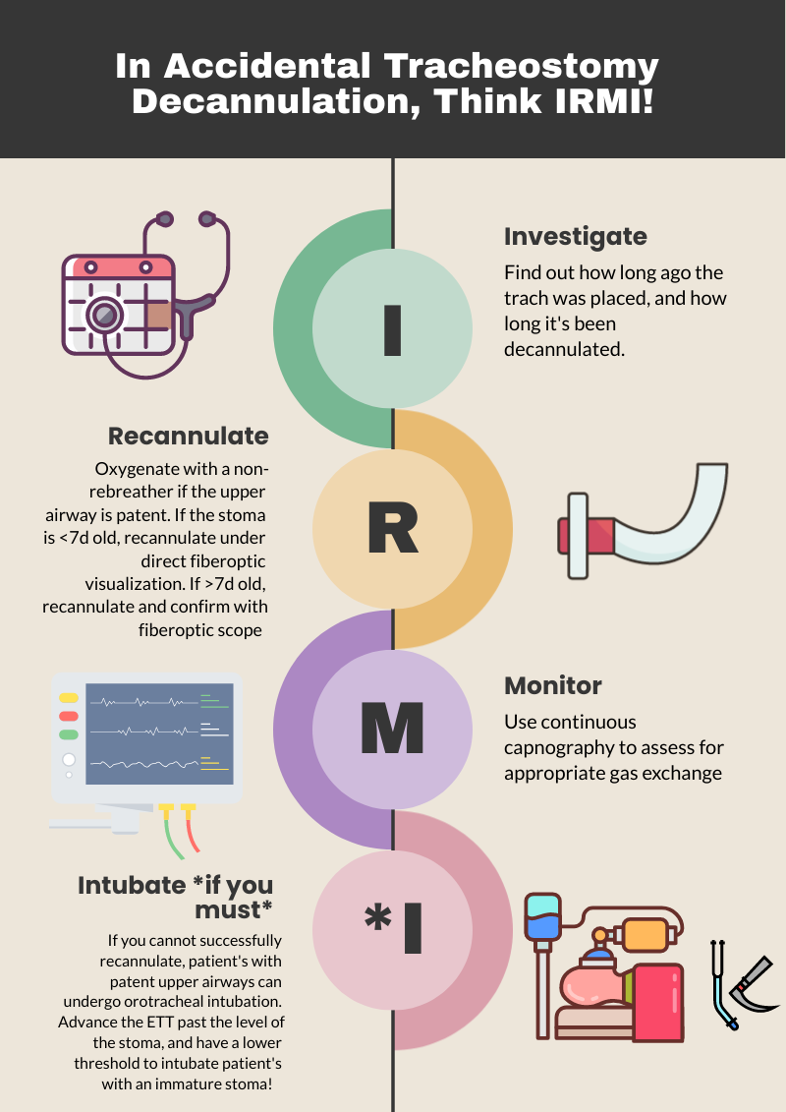

One way to approach a decannulated tracheostomy tube could be with the acronym, IRMI; Investigate, Recannulate, Monitor, and Intubate (if you must).

Investigate: How long ago was the tracheostomy tube placed? How long has it been out? What is the size of the trach? Is it cuffed or uncuffed? Why was the trach placed initially?

Cuffed vs. uncuffed: Is there a pilot balloon present? If yes, that indicates the trach is a CUFFED tracheostomy tube.

Size of tracheostomy tube: ALWAYS labeled on the neck flange.

Figure 1: Size of trach tube identification on flange. Borrowed from https://tracheostomyeducation.com/tracheostomy-tubes/.

Figure 2: Tracheostomy tube parts labeled, borrowed from ©Linda L. Morris and M. Sherif Afifi, https://www.trachresource.com/table-of-contents/

Recannulate: Oxygenate from above with non-rebreather or by blow by oxygen over the tracheostomy stoma if the patient is spontaneously breathing. If they are in respiratory distress or not spontaneously breathing, bag-valve-mask (BVM) oro-nasopharyngeal or over the stoma. You can use a pediatric mask to fit over the stoma or a LMA. Ensure to occlude the stoma if BVM from above or close the mouth if BVM from the stoma to prevent air leakage. Note, if the patient is ventilator dependent, you need a CUFFED tracheostomy tube. Obtain one tracheostomy tube of appropriate size, and a tube that’s a size down, as a stoma may begin to close the longer it’s out. For stomas less than 10 days old, grab a fiberoptic scope, as these will require recannulization under direct visualization. This is to minimize the risk of creating a false passage.

Figure 3: Depiction of creation of false passage through subcutaneous tissue when replacing tracheostomy tube. Borrowed from: Morris, L.L., Whitmer, A., & McIntosh, E. (2013). Tracheostomy care and complications in the intensive care unit. Critical care nurse, 33 5, 18-30 .

Otherwise, you can place blindly for the initial insertion. Ensure the obturator is placed inside the outer cannula tracheostomy tube prior to insertion, as it blunts the hard edge of the tracheostomy tube that can damage the membranous wall of trachea. If you meet any resistance, size down immediately, as the stoma has likely started to heal (even with a matured tracheostomy). Then remove the obturator and inflate the cuff to maintain placement (3,4).

Monitor: Once the trach tube is reinserted, it is important to monitor for appropriate placement and gas exchange. Continuous capnography is the gold standard for this. Additionally, the tube should be confirmed to be in the trachea through direct fiberoptic visualization of the trachea and carina. Be sure to assess for complications such as creation of a false lumen, which could manifest as subcutaneous emphysema (5).

Intubate if you must: If faced with a scenario where the tracheostomy tube cannot be passed through the stoma, and your patient is developing respiratory distress, you can intubate your patient orotracheally if they have a patent upper airway. The only exception to this is a patient who has had a laryngectomy, as those patients cannot be intubated orally and are obligate neck stoma breathers (6).

References

1.Bontempo, Laura J., and Sara L. Manning. "Tracheostomy emergencies." Emergency Medicine Clinics 37.1 (2019): 109-119.

2. Cheung, Nora Ham-Ting and Lena M. Napolitano. “Tracheostomy: Epidemiology, Indications, Timing, Technique, and Outcomes.” Respiratory Care 59 (2014): 895 - 919.

3. Rajendram, R., and N. McGuire. "Repositioning a displaced tracheostomy tube with an Aintree intubation catheter mounted on a fibre-optic bronchoscope." BJA: British Journal of Anaesthesia 97.4 (2006): 576-579.

4. Shah RK, Lander L, Berry JG, et al. Tracheotomy outcomes and complications: a national perspective. Laryngoscope 2012;122(1):25–9

5. Riley, Christine M.. “Continuous Capnography in Pediatric Intensive Care.” Critical care nursing clinics of North America 29 2 (2017): 251-258 .

6. McGrath B, Bates L, Atkinson D, et al, National Tracheostomy Safety Project. Multidisciplinary guidelines for the management of tracheostomy and laryngectomy airway emergencies. Anaesthesia 2012;67(9):1025–41.

Expert Commentary

Thank you for this concise summary of tracheostomy management. While most of the immediate complications of tracheostomy will occur in the ICU, these patients still frequent our emergency department with and without tracheostomy related emergencies. Despite this, patients with tracheostomy can be intimidating there is a general lack of knowledge about tracheostomy among healthcare professionals in general and emergency medicine trainees in specificity.1,2

As you have outlined, understanding both the chronicity of the tracheostomy as well as the indication for the procedure are key history when managing a displaced tube. A patient who underwent tracheostomy for failure to liberate for the ventilator likely has a patent upper airway while one placed following an ENT surgery likely poses a significant challenge for orotracheal intubation! Obtaining this history (and handing off this key information when transitioning care) can be lifesaving. Significant care should be taken when replacing a tracheostomy through an immature stoma, the usual cited maturity date being 10 to 14 days old. These should always be replaced over a fiber-optic scope with visualization of the tracheal rings and carina prior to cuff inflation and ventilation by BVM or ventilator. Failure to do so can result in severe pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax, subcutaneous emphysema, and respiratory arrest if placement into a false tract is not recognized3 . Replacement of a tracheostomy tube into a mature tract can be done blindly with an obturator in place but care should also be taken if there are any signs of trauma or bleeding. When in doubt, play it safe and obtain fiber optic visualization!

While trach replacement can be stressful under the wrong circumstances, patients with tracheostomy tubes can present with enumerable other emergencies. As with any high stress situation in resuscitation, it helps to fall back onto our ABCs, airway being of principle importance here. The immediate assessment of any patient with a tracheostomy tube in extremis should be focused on a singular question: can I ventilate the patient through this tube? In order for a patient to be effectively bagged or ventilated through a tracheostomy tube three things must be true. The tube must be patent and endotracheally placed, the tube must be cuffed, and the cuff must be inflated. Patency can be quickly assessed with passage of a flexible suction catheter. If this is unsuccessful, removal of the inner cannula (if present) and replacement with a fresh inner cannula can often resolve obstruction by secretions. If obstruction is unable to resolve, you should oxygenate from above while preparing to replace the tracheostomy tube as you have elegantly outlined.

The presence of a cuffed tube will be indicated by the presence of a pilot balloon, no reading of numbers or brand names needed! Finally, cuff inflation can be confirmed by palpation of the pilot balloon and assessing for any speech production or gurgling hear though the mouth. If the patient can phonate then the balloon is not properly inflated! If gentle inflation of the cuff does not resolve the air leak assume a ruptured cuff and replace the tracheostomy.

Tracheostomy tube care and emergencies can be very intimidating but this procedure is a valuable tool for ICU and ventilator liberation. As emergency physicians, we need to be familiar with the nuances of these devices so we can safely manage the airway just as we would any sick patient.

References

1. Whitcroft KL, Moss B, Mcrae A. ENT and airways in the emergency department: national survey of junior doctors’ knowledge and skills. J Laryngol Otol. 2016;130(2):183-189. doi:10.1017/S0022215115003102

2. Darr A, Dhanji K, Doshi J. Tracheostomy and laryngectomy survey: do front-line emergency staff appreciate the difference? J Laryngol Otol. 2012;126(6):605-608; quiz 608. doi:10.1017/S0022215112000618

3. Long B, Koyfman A. Resuscitating the tracheostomy patient in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(6):1148-1155. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2016.03.049

Matt McCauley, MD

Assistant Professor, Division of Critical Care

UW BerbeeWalsh Department of Emergency Medicine

Associate Medical Director

UW Organ and Tissue Donation

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Patton, C. Kilbane, K. (2024, Apr 15). Accidental Tracheostomy Decannulation. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by McCauley, M]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/tracheostomy-decannulation

Other Posts You May Enjoy

Intubating the Pregnant Patient in the ED

Written by: Priyanka Sista, MD (NUEM ‘20) Edited by: Steve Chukwulebe, MD (NUEM ‘19) Expert Commentary by: Samir Patel, MD

Expert Commentary

Tip for #1 - While 3-5 minutes of 100% oxygen is ideal to achieve denitrogenation, in an emergency 8 vital capacity breaths (maximal inhalation and exhalation) with a high FiO2 source is sufficient in a cooperative patient.

Tip for #2 - Airway edema is even worse in preeclamptic patients, and Mallampati scores acutely worsen DURING labor. Don’t bother with direct laryngoscopy and go straight to the video laryngoscope if it’s available.

Tip for #3 - In this scenario, the ideal LMA or supraglottic airway is one that includes a port for passage of an OG tube. Your pregnant patient in the ER with increased aspiration risk is not likely to be NPO for 8 hours like they are for anesthesiologists before surgery.

Tip for #4 - The rapid sequence dose of rocuronium is 1.2 mg/kg. You can immediately reverse rocuronium with sugammadex 16 mg/kg if necessary. For cost purposes, succinylcholine is still the best choice unless medically contraindicated.

Tip for #5 - According to ACOG, if cardiac arrest occurs in a woman greater than 23 weeks gestation, and there is no return of spontaneous circulation after 4 minutes of correctly performed CPR, a perimortem c-section should be performed with the goal of delivering the fetus by the fifth minute.

Samir K. Patel, MD

Assistant Professor

Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine

Department of Anesthesiology

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Sista, P. Chukwulebe, S. (2021, Jan 18). Intubating the pregnant patient in the ED. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Patel, S]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/intubating-the-pregnant-patient.

Other Posts You May Enjoy

Imaging in PTAs

Written by: Cameron Jones, MD (NUEM ‘23) Edited by: Vidya Eswaran, MD (NUEM ‘20) Expert Commentary by: Josh Zimmerman, MD

The Use of Imaging for Diagnosis and Management of Peritonsillar Abscesses

Among the many causes of sore throat that the EM physician may encounter, peritonsillar abscesses (PTAs) can be one of the more satisfying to diagnose and treat. A straightforward clinical diagnosis followed by a simple procedure resulting in a patient who feels much better than when they arrived...right? But what about that patient with the large, short neck and some drooling? Or the one with severe trismus giving you only the barest of glimpses at the back of their throat? Or, most feared of all, the crying child who develops lockjaw at the first glimpse of a tongue depressor? Maybe we should just get the neck CT to be on the safe side? And didn’t I hear about using ultrasound for this in some lecture?

What is a peritonsillar abscess (PTA)?

A PTA is a discrete collection of pus between the palatine tonsil capsule and the pharyngeal muscles. It should be distinguished from peritonsillar cellulitis, which is an inflammatory reaction of the same area without a definitive collection. PTAs are often preceded by tonsillitis or pharyngitis with subsequent progression of the infection. However, they may also occur due to salivary gland obstruction without preceding tonsillitis or pharyngitis. Peritonsillar abscess is often considered a clinical diagnosis based on classic symptoms and exam findings:

Throat pain (sometimes worse on the side of the abscess, but not always)

“Hot potato” or muffled voice

Unilateral swollen and erythematous tonsil +/- appreciable fluctuance

Uvula deviation

What are signs or symptoms suggestive of a more dangerous diagnosis?

Though sometimes mistakenly considered features of more concerning deep space neck infections, all of the following can also be seen with PTA:

Neck swelling

Trismus

Pooling of saliva (though this should be minor, with minimal drooling)

Other findings or symptoms of more serious deep space infections, such as retropharyngeal abscess:

Toxic appearance

Respiratory distress

Anxious appearance or leaning forward into “sniffing position”

Significant drooling

Neck pain or limited ROM out of proportion to presumed diagnosis

When should imaging be considered in the patient with suspected PTAs?

Routine imaging is not indicated for stable patients with a presumptive diagnosis based on exam. Sensitivity and specificity figures in the EM and ENT literature based on clinical exam alone are actually not very high (sensitivity <80% and specificity approximately 50%). However, these oft-cited figures are based on a comparatively small cohort of patients with presumed PTA, and in the large majority of missed diagnoses among this data, the true diagnosis is tonsillitis or peritonsillar cellulitis. CT scans, particularly contrast studies and those involving radiation of the head and neck, are not without risk, and should not be considered a screening study in well-appearing patients. Therefore, the use of imaging by ED physicians in evaluation of PTAs should really be reserved for 3 purposes:

Ruling out serious deep space neck infections, such as retropharyngeal abscesses, in a patient with signs of peritonsillar swelling but some other concerning sign or symptom, as discussed above.

- CT of the neck with contrast is best used for this purpose

Differentiating PTA from peritonsillar cellulitis or tonsillitis by identifying a discrete fluid collection

Guiding drainage in order to improve first-attempt success

- Intraoral or submandibular/transcervical ultrasounds are most appropriate for these purposes

There are few prospective studies examining the use of CT in uncomplicated PTAs, and those patients with red flags or signs of airway compromise are typically excluded. CT of the neck with IV contrast is nearly 100% sensitive and 75% specific for PTA and similarly accurate for the diagnosis of more dangerous conditions such as retropharyngeal abscesses. Increasingly, ultrasound has also become a useful option for better characterizing the location of abscesses in PTAs.

Ultrasound offers the added utility of bedside confirmation of a drainable fluid collection and, depending on provider comfort and patient tolerance, may provide real-time guidance for needle drainage. As with other applications of ultrasound, the provider must be comfortable with the technique and relevant anatomy. Prospective data indicates EM providers can become comfortable with tonsillar ultrasound technique in as few as 3-4 patients. In its use in the ED setting, ultrasound has demonstrated nearly 100% sensitivity in differentiating abscess from non-drainable inflammation or cellulitis. Thus, using ultrasound to confirm abscess in those suspected to have PTA may allow patients without drainable fluid collections to avoid unnecessary aspiration attempts.

Peritonsillar abscess seen on submandibular ultrasound. Adapted from Huang et al.

Arrows indicating edges of the abscess

T : Tonsil

* : Submandibular gland

Peritonsillar abscess on CT. Adapted from Kew et al.

Arrowheads indicating edges of the abscess.

Is imaging useful for guiding drainage of PTAs?

Ultrasound has also been studied for its utility in guiding drainage and increasing success rate of aspiration attempts. Some studies have reported low patient tolerance or mechanical challenges when using real-time intraoral ultrasound to guide drainage. However, ultrasound has also been shown to improve success-rate of aspiration attempts even when it is used for preceding visualization of the abscess and not for guided drainage.

More recently, extraoral ultrasound approaches, such as transcervical/ submandibular, have also been studied as an alternative to intraoral techniques, which can be challenging due to mechanical challenges, severe trismus, or patient discomfort. Very limited data suggests submandibular ultrasound may have lower sensitivity compared to intraoral ultrasound when evaluating PTAs, so caution is also warranted when utilizing this technique.

Intraoral ultrasound approach

(adapted from Secko, Sivitz, et al.)

Submandibular ultrasound approach

(adapted from Secko, Sivitz et al.)

What about imaging in kids?

CT scans are often ordered in pediatric patients, who may have challenging exams due to patient intolerance, and these imaging studies are particularly common in community settings where ENT expertise is not readily available. Clinical accuracy for diagnosing PTA in children appears even lower than in adults, though, as with adults, in most children incorrectly diagnosed with PTAs, the true diagnosis is tonsillitis without a drainable abscess. Many providers would also prefer to avoid the added radiation exposure of CT scans amongst this population. Thus, extraoral ultrasound approaches may be particularly helpful in pediatric patients, many of whom are unlikely to cooperate with intraoral ultrasound. Transcervical ultrasound has also been shown to reduce length of stay, CT radiation exposure, and procedures performed amongst pediatric patients with suspected PTAs, with no change in readmission rates or treatment failures. Although the extraoral ultrasound approach appears to be more technically feasible in children, use of ultrasound may also be more logistically challenging and staffing-dependent. Scans in these studies were performed and read by radiology technicians and radiologists.

So what is a reasonable approach to incorporating imaging in suspected PTAs?

The growing body of evidence described above has led to several expert recommendations that ultrasound be the first-line imaging for suspected PTAs. While there is variability in different departments regarding the ED provider’s comfort with bedside tonsillar ultrasound or, alternately, the availability of technicians and radiologists for interpreting formal ultrasounds. However, the use of ultrasound in non-toxic patients with suspected PTA has been shown to be highly effective in differentiating PTAs from peritonsillar cellulitis or tonsillitis and may save patients the discomfort and time of an unnecessary procedure. CT imaging still has its place in those patients with less certain diagnoses or concerning symptoms, but should be reserved for specific scenarios rather than being ordered routinely. The following is an evidence-based algorithm for incorporating ultrasound and CT imaging into the emergency department evaluation of these patients

* : toxic appearance, substantial drooling, respiratory distress, severe neck pain or swelling, inability to fully range neck

+ : Most patients can be safely discharged with oral antibiotics, return precautions, and ENT follow-up. Exceptions include those patients who are unable to tolerate oral medications, those with signs or symptoms of severe sepsis, patients with severe dehydration, or patient with severe comorbidities or immunocompromised state

Expert Commentary

Thank you for an excellent review of a common ED diagnosis. Sore throats are ubiquitous presenting complaints in any major ED. The final diagnosis is often uncomplicated pharyngitis, however, recognizing the early and often subtle signs of more serious conditions before a true life threat develops is a critical role for the emergency physician. While peritonsillar abscesses (PTA) in and of themselves are not typically life threatening, many of the signs and symptoms can overlap with those of more critical diagnoses such as retropharyngeal abscesses and epiglottitis.

So, that said, when should you consider imaging a patient with a suspected PTA or acute sore throat in general?

The discussion above does a thorough review evidenced based imaging practices and offers a reasonable flowsheet to guide this decision. In clinical practice imaging should help answer one of two questions:

Is a discrete fluid collection present that is amenable to drainage?

Are there findings of retropharyngeal or other deep space infection rather than a simple PTA?

I have made it my practice to consider imaging before any attempt at I&D or further care in the following circumstances:

Any patient toxic in appearance or with unstable vital signs

Any patient demonstrating signs of airway compromise

Meningismus on exam

Patients in which at PTA cannot be clearly visualized or lacking the typical secondary findings on exam

With that list in mind, let us delve into the topic a bit more in detail. Peritonsillar abscesses represent accumulation of purulent fluid which are unlikely to resolve spontaneously. Some studies have shown that drainage alone results in >90% cure rate even without antimicrobial therapy. Classically, a PTA will present with trismus, severe pharyngitis, and on pharyngeal exam a displaced tonsil, typically inferiorly and medially, as well as uvular deviation contralateral to the abscess. PTA can sometimes be confused with peritonsillar cellulitis on examination solely and is often one of the reasons clinicians opt for imaging. Peritonsillar cellulitis does not require drainage as there is no discrete fluid collection. When there is a more subtle exam, this is one scenario in which imaging may be helpful.

A practical approach that many ED physicians utilize is to consider a trial of drainage when the diagnosis is readily evident on exam. As mentioned above, when the classic findings of a displaced tonsil and uvula are present one can have a high probability of successful drainage.

Adjunct therapy – abx and steroids

The scope of this segment is meant to focus on imaging and diagnostics but it is worth a brief moment to discuss antimicrobials and adjunct therapy. While procedural drainage alone results in significant cure rates, it remains common practice to treat PTA’s with antimicrobial therapy as well. A common misconception is that PTAs are a result of Streptococcal infections. While Group A Strep is isolated from cultures, these typically tend to be polymicrobic infections with Fusobacterium additionally being a frequent culprit organism. As such, antibiotic therapy tends to be more broad spectrum with coverage of anaerobic organisms included. First line therapy remains a penicillin based antibiotic regimen. Intravenously this can be ampicillin-sulbactam (Unasyn), Piperacillin-Tazobactam (Zosyn) or Ceftriaxone Plus Metronidazole. In the penicillin allergic patient Clindamycin is a reasonable alternative. When transitioning to oral therapies, Amoxicillin-Clavulanate (Augmentin) is typically first line therapy with Clindamycin providing a reasonable alternative in penicillin allergic patients. Therapy typically is for a full 10 days.

A brief note should be made regarding steroid therapy as well. Steroids have been shown to provide significant symptomatic relief including decreasing length of symptoms and overall severity. I typically will give patients a single dose or oral or IV Dexamethasone 10 mg as part of their treatment.

Joshua Zimmerman, MD

Emergency Medicine Physician

Northwestern Lake Forest Hospital

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Jones, C. Eswaran, V. (2021, Jan 11). Imaging in PTAs. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Zimmerman, J]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/imaging-in-PTAs.

Other Posts You May Enjoy

References

Carratola, M. C., Frisenda, G., Gastanaduy, M., & Lindhe Guarisco, J. (2019). Association of Computed Tomography With Treatment and Timing of Care in Adult Patients With Peritonsillar Abscess. Ochsner Journal, 19, 309–313. https://doi.org/10.31486/toj.18.0168

Costantino, T. G., Satz, W. A., Dehnkamp, W., & Goett, H. (2012). Randomized Trial Comparing Intraoral Ultrasound to Landmark-based Needle Aspiration in Patients with Suspected Peritonsillar Abscess. Academic Emergency Medicine, 19(6), 626–631. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01380.x

Cunha, B., Filho, A., Sakae, F. A., Sennes, L. U., Imamura, R., & De Menezes, M. R. (n.d.). Intraoral and transcutaneous cervical ultrasound in the differential diagnosis of peritonsillar cellulitis and abscesses Summary. Brazilian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology, 72(3), 377-81. http://www.rborl.org.br/

Fordham, M. T., Rock, A. N., Bandarkar, A., Preciado, D., Levy, M., Cohen, J., … Reilly, B. K. (2015). Transcervical ultrasonography in the diagnosis of pediatric peritonsillar abscess. The Laryngoscope, 125(12), 2799–2804. https://doi-org/10.1002/lary.25354

Froehlich, M. H., Huang, Z., & Reilly, B. K. (2017, April 1). Utilization of ultrasound for diagnostic evaluation and management of peritonsillar abscesses. Current Opinion in Otolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOO.0000000000000338

Herzon, F. S., & Martin, A. D. (2006). Medical and Surgical Treatment of Peritonsillar, Retropharyngeal, and Parapharyngeal Abscesses. Current Infectious Disease Reports, 8:196–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11908-006-0059-8

Huang, Z., Vintzileos, W., Gordish-Dressman, H., Bandarkar, A., & Reilly, B. K. (2017). Pediatric peritonsillar abscess: Outcomes and cost savings from using transcervical ultrasound. The Laryngoscope, 127(8), 1924–1929. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.26470

J Scott, P. M., Loftus, W. K., Kew, J., Ahum, A., Yue, V., & Van Hasselt, C. A. (2020). Diagnosis of peritonsillar infections: a prospective study of ultrasound, computerized tomography and clinical diagnosis. The Journal of Laryngology and Otology, 113, 229–232. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022215100143634

Kew, J., Ahuja, A., Loftus, W. K., Scott, P. M. J., & Metreweli, C. (1998). Peritonsillar Abscess Appearance on Intra-oral Ultrasonography. Clinical Radiology (Vol. 53).

Lyon, M., & Blaivas, M. (2005). Intraoral Ultrasound in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Suspected Peritonsillar Abscess in the Emergency Department. Academic Emergency Medicine, 12(1), 85–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2005.tb01485.x

Nogan, S., Jandali, D., Cipolla, M., & DeSilva, B. (2015). The use of ultrasound imaging in evaluation of peritonsillar infections. The Laryngoscope, 125(11), 2604–2607. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.25313

Patel, K. S., Ahmad, S., O’leary, G., & Michel, M. (1992). The role of computed tomography in the management of peritonsillar abscess. Otolaryngology--Head and Neck Surgery, 107(6), 727-732. https://doi.org/10.1177/019459988910700603.1

Powell, J., & Wilson, J. A. (2012). An evidence-based review of peritonsillar abscess. Clinical Otolaryngology, 37(2), 136–145. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1749-4486.2012.02452.x

Salihoglu, M., Eroglu, M., Osman Yildirim, A., Cakmak, A., Hardal, U., & Kara, K. (2013). Transoral ultrasonography in the diagnosis and treatment of peritonsillar abscess. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinimag.2012.09.023

Valdez, T. and Vallejo, J., 2016. Infectious Diseases In Pediatric Otolaryngology. Springer International Publishing.

Epistaxis Management

Written by: Peter Serina, MD, MPH (NUEM ‘22) Edited by: Danielle Miller, MD (NUEM ‘19) Expert Commentary by: Seth Trueger, MD, MPH

Expert Commentary

Great overview by Dr. Serina and Dr. Miller of this core EM topic. Epistaxis is in many ways an archetype of the EM problem: it happens to nearly everyone at some point in their lives; most people do fine (and don’t ever need to seek care); most who seek care need a little attention but not much intervention; a small fraction account for most of the work but still generally do well with management; and a tiny fraction of a percent need consultants, may be horribly sick or need rare procedures. There are a lot of potential ways to manage epistaxis (especially those that are only a bit difficult to control) and I find it helpful to distill into fewer options so that things don’t get drawn out.

Much like dysrhythmias, step 1 is stable vs unstable and if they are going to need ENT/IR/airway management, the rest is a waste and don’t dawdle to delay definitive treatment. This is very rare, and most patients go into a stable, stepwise approach:

1) Pinchers

I find most patients either resolved by the time we see them, or simply need some basic nasal pinching. Either way, I use this as an opportunity to counsel patients and *actually demonstrate* what to do if this happens again at home. That includes me pinching their nose in the right place with the right amount of force, and explaining each step so that they understand the rationale (eg blow your nose to get rid of mucus and clots so there are clean surfaces; tilt your head forward so blood doesn’t trickle down your throat and make you release your pinching). I also always put these instructions in their DC paperwork:

If your nose starts to bleed:

BLOW YOUR NOSE: this sounds backwards but it will clear out any clot or mucus that will stop a proper clot from forming

PINCH YOUR NOSTRILS TOGETHER: hold the soft part of your nose together (just below the bony bridge)

DO NOT LET GO FOR 20-30 MINUTES: not even for a second. Do not switch hands. Do not check to see if it's working. Watch an entire TV show on your phone while pinching your nose.

TILT YOUR HEAD FORWARD: this will stop blood from running down your throat and making you feel miserable

Things you can do to prevent nosebleeds:

Keep all foreign bodies out of the nose. This includes fingertips and tissue paper -- do not put anything up your nose

Use a humidifier at home to help keep your nose skin moist

Return to the ER if you have any concerning symptoms including:

bleeding that won't stop after 30 minutes of continuous pressure

weakness

dizziness

any other new or concerning symptoms

2) Packers

This is where there is a lot of leeway. If there is something obvious for me to cauterize, I will use some silver nitrate. If I think there is a reasonable chance of success, I will try temporary packing with a TXA-soaked pledget for 10 minutes. If I don’t think that will work, or if that fails, I go straight to a rhinorocket which I also soak in TXA (instead of water); I haven’t seen data for this but it is cheap and safe so why not?

3) Phone calls

If packing fails, ENT consult. Not fun and can take some time (and usually ends up with a recommendation for amox/clav that probably isn’t necessary) but fortunately is rare.

Seth Trueger, MD, MPH

Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine

Department of Emergency Medicine

Northwestern University

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Serina, P. Miller, D. (2020, Aug 17). Epistaxis Management [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Treuger, S]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/epistaxis-management.

Other Posts You May Enjoy

References

Simple Steps To Auricular Hematoma Drainage

A step-by-step guide to management of auricular hematoma.