Written by: Alexandra Franiek, MD (NUEM ‘26) Edited by: Savannah Vogel, MD (NUEM ‘24)

Expert Commentary by: Matt Levine, MD

Introduction

Facial fractures are responsible for greater than 400,000 Emergency Department visits annually in the United States (1). Facial injuries predominantly affect young adults, more often males, and are often the result of motor vehicle collisions (MVC), physical assault and recreational sport. Because these bones form the anterior facial skeleton, they are highly associated with traumatic brain injury, cervical spine injury, as well as airway compromise (2).

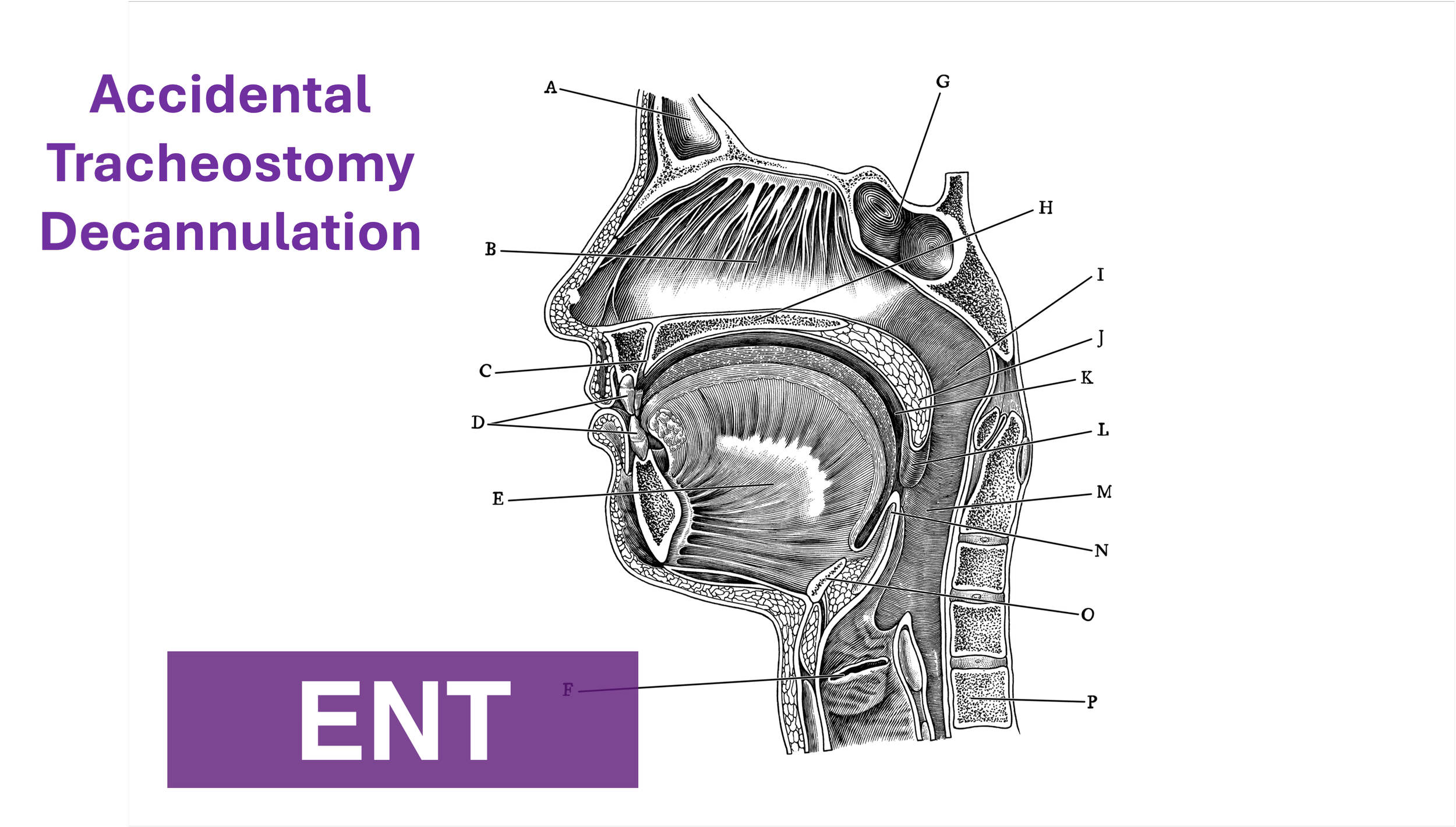

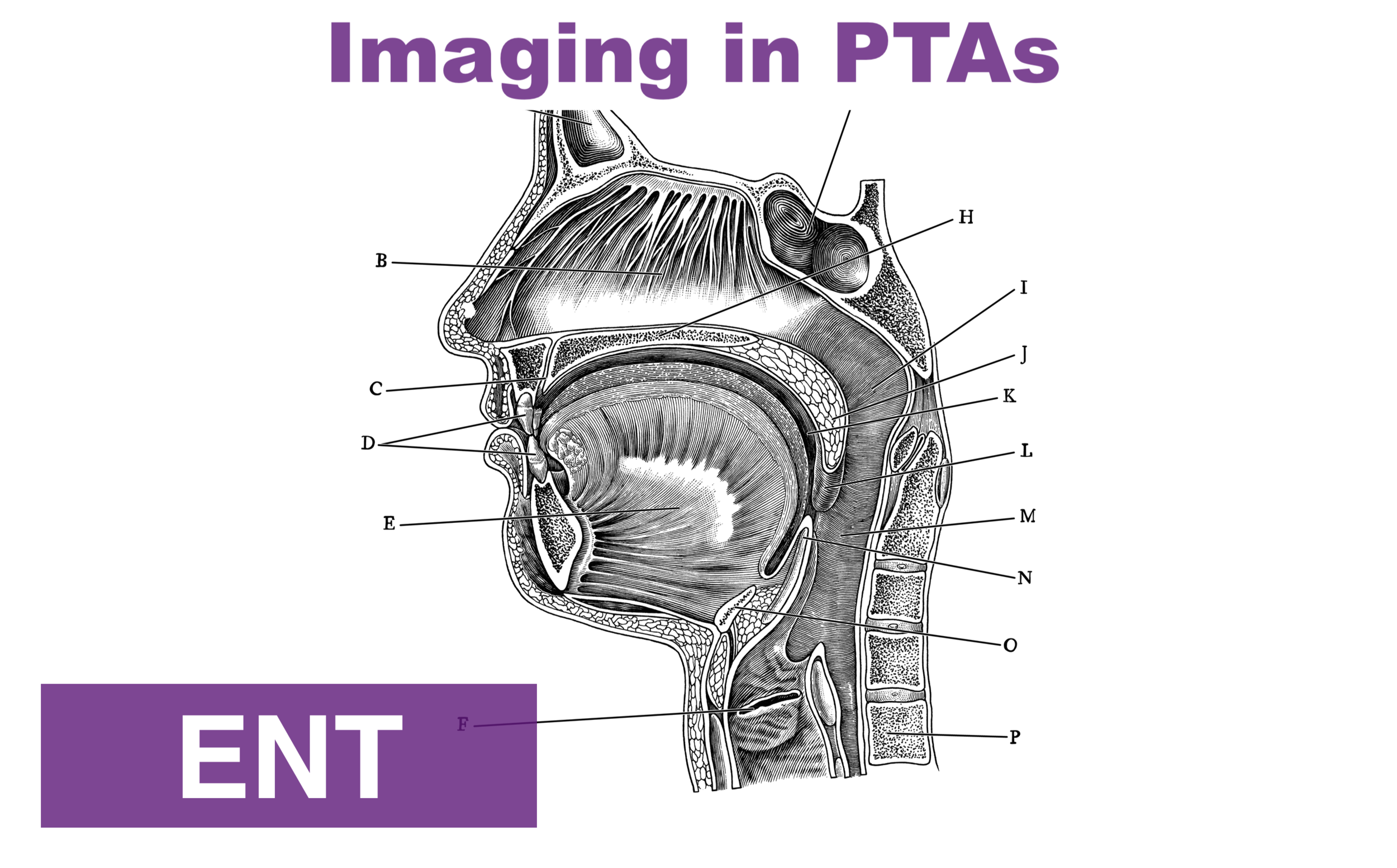

Anatomy

The facial bones can be organized into the following areas for clinical evaluation:

Frontal Bone

Orbit

Midface

Mandible

Initial Assessment

As facial fractures usually present as traumas, assessment typically begins with the primary survey. Lower facial fractures which may affect the oropharynx and therefore breathing are often identified first. Fractures involving the orbit are often identified in Disability when assessing pupillary response. The secondary survey involves examining all facial structures including vasculature, nerves, muscles, glands and overlying skin which are commonly injured (3).

Midface (Le Fort Fractures)

Classification

Le Fort I: Mobile segment(s): Maxilla (sometimes referred to as the “floating palate”)

Le Fort II: Mobile segment(s): Maxilla and nose as a joint segment (pyramidal)

Le Fort III: Mobile segment(s): Maxilla, nose, and orbital rim as joint segment. The entire face will move, and the globe will be secured in place by the optic nerve.

Diagnosis

Le Fort I: Lip swelling, open bite malocclusion, ecchymosis involving the buccal vestibule and palate, mobility of the maxilla.

Le Fort II: Intercanthal space widening (particularly with nasal septum involvement), mobility of the maxilla and nose as a unit, ecchymosis involving the buccal vestibule and palate, bilateral periorbital edema and ecchymosis (racoon eyes), epistaxis, CSF rhinorrhea and open bite malocclusion.

Le Fort III: Bilateral periorbital edema and ecchymosis (raccoon eyes), ecchymosis of the buccal vestibule and palate, lengthening of facial height and facial flattening (dish-face deformity), orbital hooding and enophthalmos, mastoid ecchymosis (Battle’s sign), CSF rhinorrhea, CSF otorrhea, and hemotympanum.

To examine, place one hand on the forehead (or nasal bridge) for stabilization. Use the other hand to grasp the maxillary teeth (midface). Gently rock the lower hand.

CT facial bones +/- CT brain, CT angiography is the gold standard.

Management

Stabilization of life-threatening injuries is priority. Airway obstruction mostly occurs due to bleeding into the upper airway or distorted anatomy. Le Fort II-III have the highest risk of life-threatening hemorrhage compared to other facial injuries.

After stabilization, consult Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery (OMFS) for definitive surgery with Open Reduction Internal Fixation. In situations where general anesthesia is not feasible, e.g. due to frailty or comorbidities, a conservative approach with nasogastric feeds is possible often at the cost of function and appearance. 90% of patients will have concurrent ocular injuries so ophthalmology consult is also warranted (1,2,4,5).

Isolated Nasal Fractures

The nose is the most commonly fractured facial bone.

Diagnosis

Visually inspect and palpate nasal and septal cartilage.

Difficulty breathing out of one nostril can indicate septal deviation or hematoma.

Internally assess for epistaxis, hematomas and CSF rhinorrhea.

Unlike other facial fractures, imaging is not required for an isolated nasal fracture. If confirmatory imaging is desired, high-resolution ultrasound has greater accuracy than CT (100 compared to 92%). In complex nasal fractures or if other facial fractures are suspected or present, facial CT is indicated (1).

Two nasal fractures indicated by purple arrows:

Management

Address epistaxis (for more information, please refer to this informative NUEM Blog https://www.nuemblog.com/blog/epistaxis-management) and hematomas first, then reduce fractures. For septal hematomas, early drainage is key to preventing septum necrosis and subsequent saddle deformity. Packing and nasal splints aid in compression of the septum to prevent re-accumulation. Antibiotics should be administered. Follow up with Otolaryngology (6).

If patients attend within hours after injury, closed reduction can usually be attempted. If swelling has developed, reduction should be deferred as it can be difficult to appreciate deformities and anatomical shape. Always provide analgesia prior to manipulation; consider a hematoma block or bilateral infraorbital nerve blocks. To reduce, apply gentle pressure (as detailed in the image below) until the nose returns to the desired position. A “click” may be appreciated. If reduction is deferred, follow up in five to seven days with an otolaryngologist is appropriate; the patient may ultimately undergo (septo)rhinoplasty (1,5).

https://pocketdentistry.com/nasal-fractures-3/

Mandibular Fractures

Mandibular fractures are the second most common facial fractures after nasal, and the most common fracture site for gunshot wounds and assault (1). Mandibular fractures are considered bilateral until proven otherwise; always assess for a second fracture on the opposite side of ring.

Diagnosis

Patient-reported pain with movement.

Bite malalignment (widened or shifted unilaterally).

Evidence of open fracture on oral examination, including disruptions in mucosa, sublingual hematoma and dental fractures.

Plug the patients ears with your index fingers and palpate the mandibular condyles. Then ask the patient to open and close their jaw to palpate for condylar fractures.

Tongue blade bite test – Insert a tongue depressor into the patients mouth, ask them to bite down. Then twist the blade. If it can be cracked or broken without pain, this is considered negative for fracture (88-95% sensitive, NPP between 92-100%).

Panoramic radiographs (Panorex) are useful to evaluate suspected simple fractures and to rule out occult fractures. For complex fractures, CT is preferred. Order a chest radiograph if there are missing teeth to exclude aspiration.

Management

Stabilize the airway with Barton’s bandage. If there is minimal intraoral bleeding, asking the patient to bite down on gauze can promote hemostasis. If there is significant intraoral bleeding, secure the airway. Antibiotics have uncertain utility but are the current practice and should target oral anaerobes. Consult otolaryngology or OMFS. While some fractures are managed non-operatively with dietary (e.g. liquids and soft diet) and functional restrictions, greater than 90% are managed with surgical repair (1,2). Open reduction and internal fixation with plates and screws allows for shorter healing time and is often preferred to closed reduction (7).

Barton’s bandage

https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/dental-disorders/dental-emergencies/mandibular-dislocation

References:

Chukwulebe S, Hogrefe C. The Diagnosis and Management of Facial Bone Fractures. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2019;37(1):137–51.

Hedayati; T, Amin DP. Trauma to the Face. In: Tintinalli JE, Ma OJ, Yealy DM, Meckler GD, Stapczynski SJ, Cline DM, et al., editors. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine : a Comprehensive Study Guide [Internet]. Ninth. New York: New York : McGraw-Hill; 2020. Available from: https://accessmedicine-mhmedical-com.turing.library.northwestern.edu/content.aspx?bookid=2353§ionid=222323488

Mayersak RJ. Initial evaluation and management of facial trauma in adults [Internet]. UpToDate. 2021 [cited 2023 Mar 15]. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/initial-evaluation-and-management-of-facial-trauma-in-adults?search=facial fractures&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~63&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H24

Patel BC, Wright T, Waseem M. Le Fort Fractures [Internet]. StatPearls. 2022 [cited 2023 Mar 15]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526060/

Boswell KA. Management of Facial Fractures. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2013;31(2):539–51.

Malaty J. Facial and skull fractures. In: Fracture Management for Primary Care and Emergency Medicine. Fourth. Amsterdam; 2021.

Koshy J, Feldman E, Chike-Obi C, Bullocks J. Pearls of Mandibular Trauma Management. Semin Plast Surg. 2010;24(04):357–74.

Expert Commentary

There are 5 major or common facial fractures that Emergency Physicians need to be familiar with:

Le Fort

Mandible

Nose

Orbital blow out

ZMC (zygomataticomaxillary complex)

Dr. Franiek covered Le Fort, nasal, and mandible fractures in this installment. I’d like to add some pearls to the nice foundation she laid out.

Le Fort fractures are often associated with significant intracranial or cervical spine injury. Always image the brain and cervical spine in the cases. Most of these I have seen have been elderly patients with impressive exam findings. A classic exam finding is the “dish face” deformity, when the midface curves inward like a dish. A quick and easy exam maneuver is to grasp the patient’s middle upper incisors and see if the midface slides forward. While classic teachings of these fractures have neat drawings with characteristic fracture patterns, the actual CT imaging does not have a single coronal image money shot that looks like these textbook images. Instead, the radiologist typically finds many separate fractures on various slices and is able to discern the diagnosis. Keep in mind that there can be asymmetric Le Fort injuries (i.e. Le Fort II on one side and III on the other). The actual Le Fort terminology is an oversimplification of the myriad of fractures these patients have. It is useful though for interprofessional communication about the injury, using the Le Fort terminology rather than listing each of the many fractures.

Nasal fractures are so common that all Emergency Physicians need to have scripts for patient discussions to minimize unnecessary imaging. Many patients present requesting x rays of their noses. Nasal x rays are both inaccurate and useless. Cartilaginous injury cannot be radiographically diagnosed. Longitudinal fractures have the same orientation as the nasomaxillary suture and nasociliary groove, leading to misreads. Nasal fractures are managed by external appearance, not radiographic findings, so find a script to reassure patients that their nose will be fine without x rays. In the end patients don’t really want x rays, they just want to know that their nose will look right. Oh yeah, and Dr Franiek mentioned reduction with gentle pressure. In my experience, gentle pressure doesn’t get the job done.

For imaging suspected mandible fractures, modalities are CT, plain film mandible series, and panorex x rays. What is available to the provider may vary between institutions. Mandible x rays are operator dependent and many technicians do not perform them frequently enough to get those really good unobstructed oblique views that are required. Panorex films require a specific imaging device that, even if available, is often housed outside the ED. A radiologist must interpret the images since there are funny “ghost images” and artifacts that may confuse many practitioners. CT is typically a fine choice and gives the best view of the condyles, which may be suboptimally imaged with plain films or panorex.

If you see a laceration between the teeth in blunt trauma, there is almost always a mandible fracture right under it, so this is an open fracture! The tongue blade test is quite useful for those cases that you are not sure whether to proceed with imaging. It needs to be performed on both sides of the mouth. Have the patient clench down on the tongue blade with their molars, then twist it until it cracks. If that maneuver does not cause pain then it is a negative test, highly sensitive for ruling out a mandible fracture. Repeat on the other side with a new tongue blade.

Matt Levine, MD

Emergency Medicine Physician, Northwestern Memorial Hospital

Associate Professor, Feinberg School of Medicine

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Franiek, A. Vogel, S. (2025, Apr 29). Facial Fractures: Midface and Mandible. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Levine, M]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/facial fractures-midface and mandible

Other Posts You May Enjoy