Written by: Kishan Ughreja, MD (NUEM ‘23) Edited by: Sean Watts, MD (NUEM ‘22)

Expert Commentary by: Dana Loke, MD (NUEM ‘21)

Utility of Sodium Bicarbonate in Cardiac Arrest

Use of sodium bicarbonate as empiric therapy in cardiac arrest has been an area of controversy. During cardiac arrest hypoxia and hypoperfusion results in severe metabolic acidosis and subsequent impaired myocardial contractility, decreased efficacy of vasopressors, and increased risk of dysrhythmias. Previous ACLS guidelines recommended use of sodium bicarbonate to mitigate these effects; however, harms are also associated with its routine use including compensatory respiratory acidosis, hyperosmolarity, increased vascular resistance, and reduction in ionized calcium. 1 Current guidelines no longer recommend routine use of sodium bicarbonate, except in cases of arrest secondary to hyperkalemia, TCA overdose or preexisting metabolic acidosis.2 Regardless of these recommendations, sodium bicarbonate continues to be utilized during routine management of cardiac arrest, and studies are limited in investigating its appropriate use.

The study below investigates the effect of sodium bicarbonate in patients suffering out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with severe metabolic acidosis during prolonged CPR.

Article

Clinical Question

In patients with prolonged, atraumatic out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) and severe metabolic acidosis, does sodium bicarbonate (SB) administration with transient hyperventilation improve acidosis without increased CO2 burden, enhance rates of return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), survival to admission, and favorable neurologic outcomes?

Study Design

Double-blind, prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled, single-center pilot clinical trial

Population

Inclusion criteria: Atraumatic arrest in patients ≥18yo without ROSC after 10 minutes of CPR in ED and with pH <7.1 or bicarbonate <10 mEq/L on ABG

Exclusion criteria: DNR, ECPR, ROSC w/i 10 minutes of ACLS, absence of severe metabolic acidosis on ABG after 10 minutes of CPR

Data collection over 1 year at Asan Medical Center, a tertiary referral center in Seoul, Korea

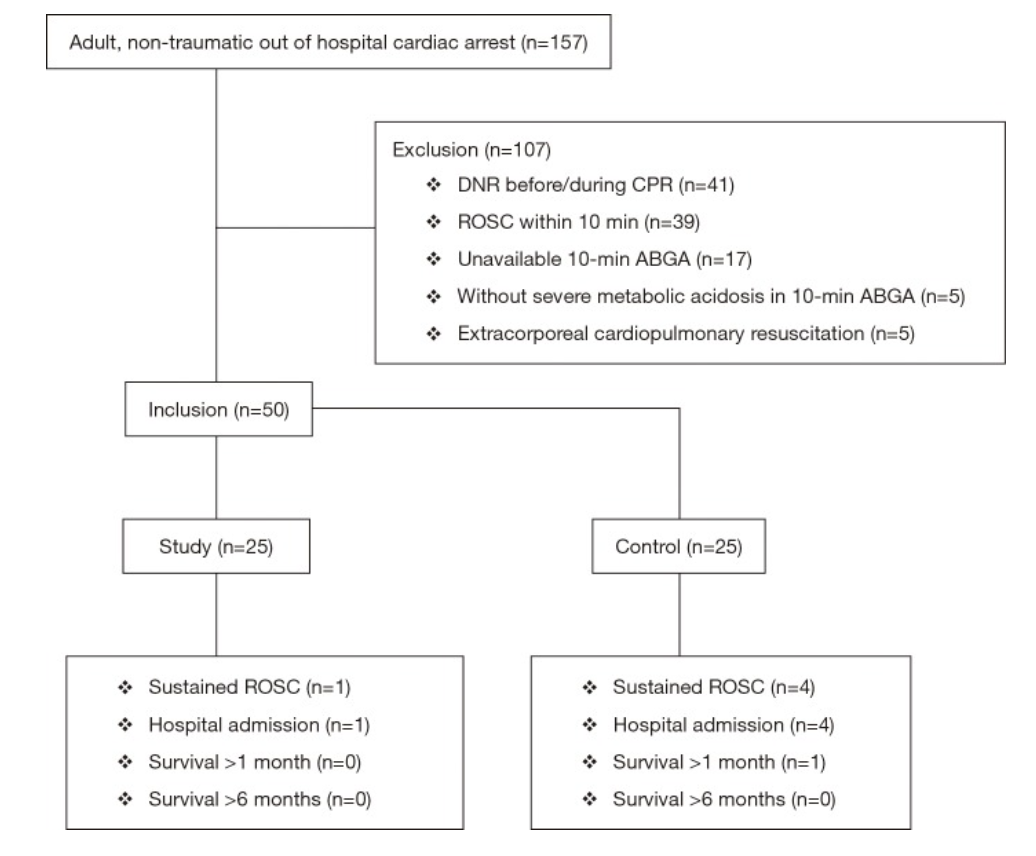

Figure 1: Patient Selection

Intervention

Sodium bicarbonate administration of 50 mEq/L over 2 minutes with concurrent increase in ventilation rate from 10 to 20 breaths per minute for 2 minutes

Control

Normal saline administration of 50 mL over 2 minutes (with same transient hyperventilation)

Outcomes

Primary

Change in acidosis (per methods section)

Secondary

Sustained ROSC — defined as restoration of a palpable pulse ≥20 min (per methods section, but listed as primary outcome in abstract)

Survival to hospital admission

Good neurological survival at 1 and 6 months (defined as cerebral performance category 1 or 2)

Results

157 patients presented with cardiac arrest, 50 enrolled per inclusion criteria

No significant differences between study and control groups regarding demographics, PMH, witnessed arrest, bystander CPR, pre-hospital and initial cardiac rhythm

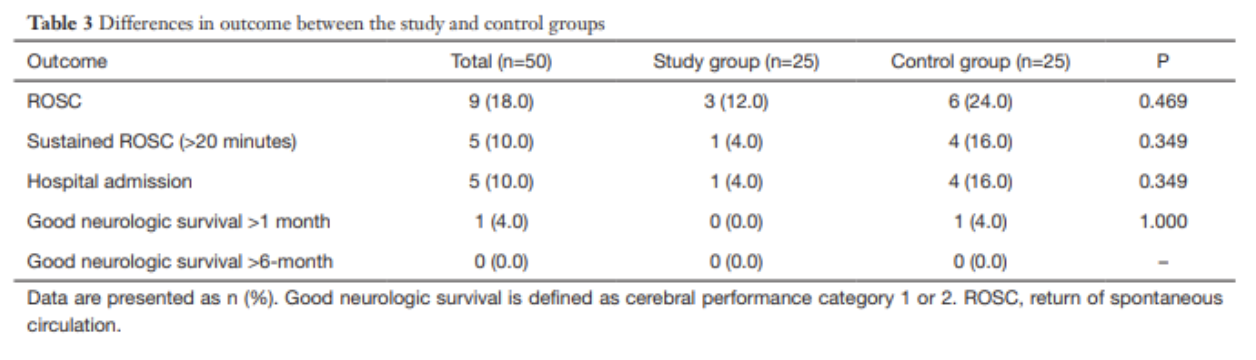

10% (n=5) of enrolled patients with sustained ROSC and admitted

No patients survived at 6 months follow up

Pre-Intervention

ABG results at 10 minutes were not significantly different between groups

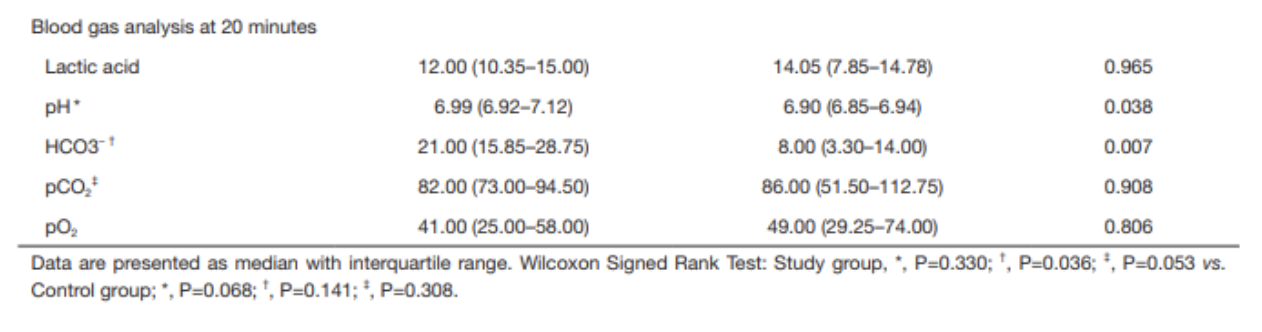

Post-intervention

ABG results at 20 minutes demonstrate that pH and HCO3- were higher in the study group than in the control group

pH 6.99 vs 6.90, p=0.038

HCO3- 21.0 vs 8.00, p=0.007

Within the study group, the increase in pH was not statistically significant after sodium bicarbonate administration; the increase in HCO3- was statistically significant (using Wilcoxon signed rank test)

No statistically significant findings in the control group after normal saline administration

No significant differences in any secondary outcomes (sustained ROSC, survival to admission, good neurologic outcome)

Strengths

Randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study design

This study adds additional information to a clinical question that has limited previous research

This study added a practical clinical intervention (hyperventilation) to counteract excessive CO2 accumulation secondary to sodium bicarbonate administration, a known deleterious effect of this compound.

Strong control over sodium bicarbonate administration (no pre-hospital administration allowed in South Korea), so authors could control when it was given and analyze ABG results at desired intervals)

Weaknesses

Small, single-center study with only 50 enrolled patients

Primary endpoint unclear from abstract vs methods, whether it was change acidosis or sustained ROSC; however, neither is truly patient-centered clinical outcome (good neurological outcome would be the ideal primary outcome)

Dosing was universal — 50 mEq/L instead of weight based (1-2 mEq/L/kg), which could result in improper dosing

Hyperventilation strategy may have benefited sodium bicarbonate administration group by countering respiratory alkalosis, however, it could have harmed the placebo group

Possible venous sampling rather than arterial for blood gas analysis at 10-minute point, though this would be a concern in any arrest setting if an arterial line could not be established in this time frame

Author’s Conclusion

“The use of sodium bicarbonate during CPR with transient hyperventilation improves acid-base status without CO2 elevation which is one of the most concerned adverse effects of sodium bicarbonate administration, but it had no effect on the improvement of the rate of ROSC and good neurologic survival. At this point, we could not advise for or against its administration, our pilot data could be used to help design a larger trial to verify the efficacy of sodium bicarbonate.”

Bottom Line

Based on this study, the use of sodium bicarbonate does not appear to improve clinically significant outcomes, though it improved acid-base status. Sodium bicarbonate should not be indiscriminately used in all cardiac arrests, and larger trials should be performed to further evaluate its impact on patient-centered outcomes.

Citation

Ahn, S., Kim, Y. J., Sohn, C. H., Seo, D. W., Lim, K. S., Donnino, M. W., & Kim, W. Y. (2018). Sodium bicarbonate on severe metabolic acidosis during prolonged cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled pilot study. Journal of thoracic disease, 10(4), 2295.

References

White, S. J., Himes, D., Rouhani, M., & Slovis, C. M. (2001). Selected controversies in cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Seminars in respiratory and critical care medicine, 22(1), 35–50. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2001-13839

Merchant, R. M., Topjian, A. A., Panchal, A. R., Cheng, A., Aziz, K., Berg, K. M., Lavonas, E. J., Magid, D. J., & Adult Basic and Advanced Life Support, Pediatric Basic and Advanced Life Support, Neonatal Life Support, Resuscitation Education Science, and Systems of Care Writing Groups (2020). Part 1: Executive Summary: 2020 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation, 142(16_suppl_2), S337–S357. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000918

Expert Commentary

Thank you Dr. Ughreja and Dr. Watts for this excellent blog post on an important topic. In medicine, we often ask “what else can we do?” but less often do we ask “is what we’re already doing effective?” This is especially important for resuscitation and cardiac arrest. Not everything that is standard-of-care is ultimately effective care, and overtreating patients can lead to other untoward effects.

In addition to the points made in the above blog, I would add a few important notes into the equation. First, the study excluded in-hospital cardiac arrest and therefore should not be considered in those patients. Second, the study also excluded those patients with early ROSC and absence of severe metabolic acidosis, effectively biasing towards inclusion of sicker patients. It is unclear how administration of sodium bicarbonate may have influenced those patients. Third, the study population was quite small and a striking majority of that population were found to have an initial rhythm of asystole. Fourth, ventilation rates were purposefully increased during bicarb administration. Though this may be practical and can potentially counteract excessive CO2 accumulation secondary to sodium bicarbonate administration, this is not common practice which leads to questions of this study’s external validity at other institutions.

So, despite this study, at this point in time we still must grapple with the “should-we-or-should-we-not” of sodium bicarbonate administration in prolonged cardiac arrest. Some scenarios certainly do require sodium bicarbonate, most notably TCA overdose and hyperkalemia. In these cases, it’s obvious what to do. But so often what we do in emergency medicine is riddled with uncertainty. An unclear cause of cardiac arrest is certainly one of those situations. Perhaps instead of mindlessly giving sodium bicarbonate to cardiac arrest patients, we should give it once or twice and look for evidence that it has had an effect. Is the rhythm narrowing? Did you obtain ROSC shortly after administration? If not, giving dose after dose of sodium bicarbonate in hopes of meaningful recovery may not be the best path forward.

Dana Loke, MD

Department of Emergency Medicine

Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine

Northwestern Memorial Hospital

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Ughreja, K. Watts, S. (2021, Dec 6). Bicarb in Cardiac Arrest. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Loke, D]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/bicarb-arrest