Written by: Chezlyn Patton, MD (NUEM ‘27) Edited by: Keara Kilbane, MD (NUEM ‘25)

Expert Commentary by: Matt McCauley, MD (NUEM ‘21)

Introduction

Tracheostomy is a common procedure in the US with over 110,000 trachs placed annually (1). Complications occur at a rate of approximately 40-50%, however most complications are minor, with only 1% being catastrophic (1). Of these devastating complications, 90% occur within the first 10 days of placement. Overall approximately 15% of tracheostomies will be decannulated accidentally, and in a critical care setting, 50% of airway related deaths were associated with accidental tracheostomy decannulation (1, 2).

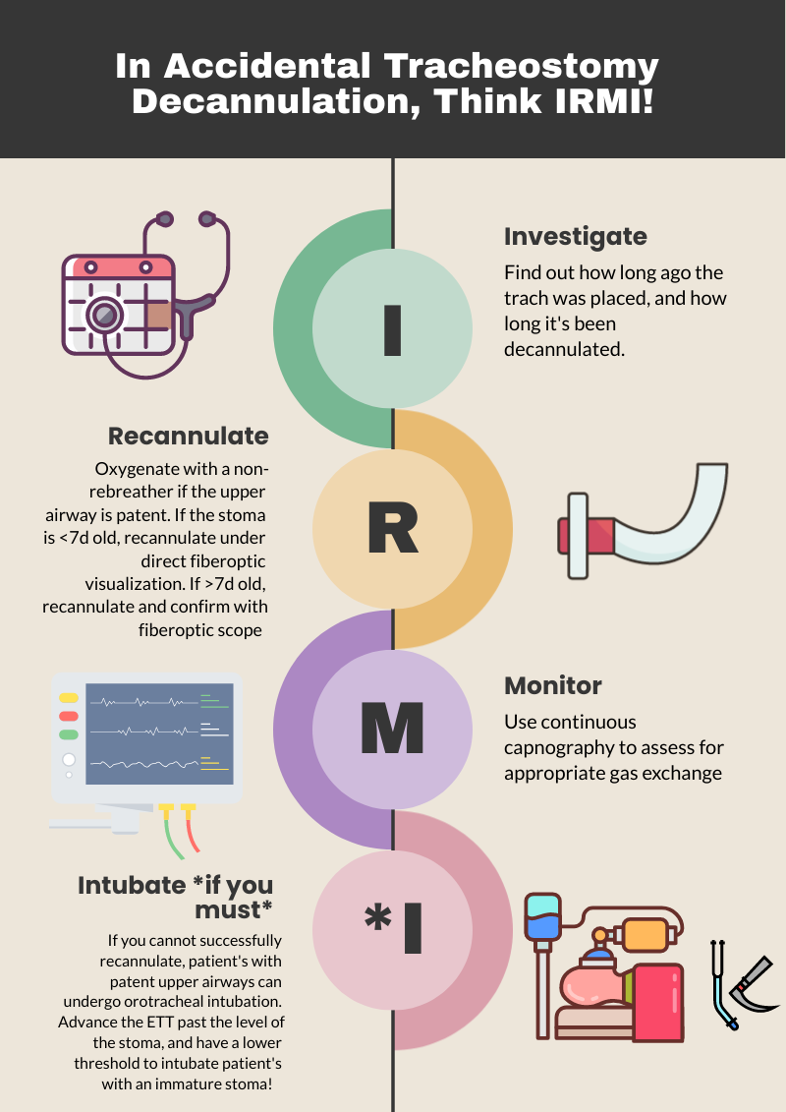

One way to approach a decannulated tracheostomy tube could be with the acronym, IRMI; Investigate, Recannulate, Monitor, and Intubate (if you must).

Investigate: How long ago was the tracheostomy tube placed? How long has it been out? What is the size of the trach? Is it cuffed or uncuffed? Why was the trach placed initially?

Cuffed vs. uncuffed: Is there a pilot balloon present? If yes, that indicates the trach is a CUFFED tracheostomy tube.

Size of tracheostomy tube: ALWAYS labeled on the neck flange.

Figure 1: Size of trach tube identification on flange. Borrowed from https://tracheostomyeducation.com/tracheostomy-tubes/.

Figure 2: Tracheostomy tube parts labeled, borrowed from ©Linda L. Morris and M. Sherif Afifi, https://www.trachresource.com/table-of-contents/

Recannulate: Oxygenate from above with non-rebreather or by blow by oxygen over the tracheostomy stoma if the patient is spontaneously breathing. If they are in respiratory distress or not spontaneously breathing, bag-valve-mask (BVM) oro-nasopharyngeal or over the stoma. You can use a pediatric mask to fit over the stoma or a LMA. Ensure to occlude the stoma if BVM from above or close the mouth if BVM from the stoma to prevent air leakage. Note, if the patient is ventilator dependent, you need a CUFFED tracheostomy tube. Obtain one tracheostomy tube of appropriate size, and a tube that’s a size down, as a stoma may begin to close the longer it’s out. For stomas less than 10 days old, grab a fiberoptic scope, as these will require recannulization under direct visualization. This is to minimize the risk of creating a false passage.

Figure 3: Depiction of creation of false passage through subcutaneous tissue when replacing tracheostomy tube. Borrowed from: Morris, L.L., Whitmer, A., & McIntosh, E. (2013). Tracheostomy care and complications in the intensive care unit. Critical care nurse, 33 5, 18-30 .

Otherwise, you can place blindly for the initial insertion. Ensure the obturator is placed inside the outer cannula tracheostomy tube prior to insertion, as it blunts the hard edge of the tracheostomy tube that can damage the membranous wall of trachea. If you meet any resistance, size down immediately, as the stoma has likely started to heal (even with a matured tracheostomy). Then remove the obturator and inflate the cuff to maintain placement (3,4).

Monitor: Once the trach tube is reinserted, it is important to monitor for appropriate placement and gas exchange. Continuous capnography is the gold standard for this. Additionally, the tube should be confirmed to be in the trachea through direct fiberoptic visualization of the trachea and carina. Be sure to assess for complications such as creation of a false lumen, which could manifest as subcutaneous emphysema (5).

Intubate if you must: If faced with a scenario where the tracheostomy tube cannot be passed through the stoma, and your patient is developing respiratory distress, you can intubate your patient orotracheally if they have a patent upper airway. The only exception to this is a patient who has had a laryngectomy, as those patients cannot be intubated orally and are obligate neck stoma breathers (6).

References

1.Bontempo, Laura J., and Sara L. Manning. "Tracheostomy emergencies." Emergency Medicine Clinics 37.1 (2019): 109-119.

2. Cheung, Nora Ham-Ting and Lena M. Napolitano. “Tracheostomy: Epidemiology, Indications, Timing, Technique, and Outcomes.” Respiratory Care 59 (2014): 895 - 919.

3. Rajendram, R., and N. McGuire. "Repositioning a displaced tracheostomy tube with an Aintree intubation catheter mounted on a fibre-optic bronchoscope." BJA: British Journal of Anaesthesia 97.4 (2006): 576-579.

4. Shah RK, Lander L, Berry JG, et al. Tracheotomy outcomes and complications: a national perspective. Laryngoscope 2012;122(1):25–9

5. Riley, Christine M.. “Continuous Capnography in Pediatric Intensive Care.” Critical care nursing clinics of North America 29 2 (2017): 251-258 .

6. McGrath B, Bates L, Atkinson D, et al, National Tracheostomy Safety Project. Multidisciplinary guidelines for the management of tracheostomy and laryngectomy airway emergencies. Anaesthesia 2012;67(9):1025–41.

Expert Commentary

Thank you for this concise summary of tracheostomy management. While most of the immediate complications of tracheostomy will occur in the ICU, these patients still frequent our emergency department with and without tracheostomy related emergencies. Despite this, patients with tracheostomy can be intimidating there is a general lack of knowledge about tracheostomy among healthcare professionals in general and emergency medicine trainees in specificity.1,2

As you have outlined, understanding both the chronicity of the tracheostomy as well as the indication for the procedure are key history when managing a displaced tube. A patient who underwent tracheostomy for failure to liberate for the ventilator likely has a patent upper airway while one placed following an ENT surgery likely poses a significant challenge for orotracheal intubation! Obtaining this history (and handing off this key information when transitioning care) can be lifesaving. Significant care should be taken when replacing a tracheostomy through an immature stoma, the usual cited maturity date being 10 to 14 days old. These should always be replaced over a fiber-optic scope with visualization of the tracheal rings and carina prior to cuff inflation and ventilation by BVM or ventilator. Failure to do so can result in severe pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax, subcutaneous emphysema, and respiratory arrest if placement into a false tract is not recognized3 . Replacement of a tracheostomy tube into a mature tract can be done blindly with an obturator in place but care should also be taken if there are any signs of trauma or bleeding. When in doubt, play it safe and obtain fiber optic visualization!

While trach replacement can be stressful under the wrong circumstances, patients with tracheostomy tubes can present with enumerable other emergencies. As with any high stress situation in resuscitation, it helps to fall back onto our ABCs, airway being of principle importance here. The immediate assessment of any patient with a tracheostomy tube in extremis should be focused on a singular question: can I ventilate the patient through this tube? In order for a patient to be effectively bagged or ventilated through a tracheostomy tube three things must be true. The tube must be patent and endotracheally placed, the tube must be cuffed, and the cuff must be inflated. Patency can be quickly assessed with passage of a flexible suction catheter. If this is unsuccessful, removal of the inner cannula (if present) and replacement with a fresh inner cannula can often resolve obstruction by secretions. If obstruction is unable to resolve, you should oxygenate from above while preparing to replace the tracheostomy tube as you have elegantly outlined.

The presence of a cuffed tube will be indicated by the presence of a pilot balloon, no reading of numbers or brand names needed! Finally, cuff inflation can be confirmed by palpation of the pilot balloon and assessing for any speech production or gurgling hear though the mouth. If the patient can phonate then the balloon is not properly inflated! If gentle inflation of the cuff does not resolve the air leak assume a ruptured cuff and replace the tracheostomy.

Tracheostomy tube care and emergencies can be very intimidating but this procedure is a valuable tool for ICU and ventilator liberation. As emergency physicians, we need to be familiar with the nuances of these devices so we can safely manage the airway just as we would any sick patient.

References

1. Whitcroft KL, Moss B, Mcrae A. ENT and airways in the emergency department: national survey of junior doctors’ knowledge and skills. J Laryngol Otol. 2016;130(2):183-189. doi:10.1017/S0022215115003102

2. Darr A, Dhanji K, Doshi J. Tracheostomy and laryngectomy survey: do front-line emergency staff appreciate the difference? J Laryngol Otol. 2012;126(6):605-608; quiz 608. doi:10.1017/S0022215112000618

3. Long B, Koyfman A. Resuscitating the tracheostomy patient in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(6):1148-1155. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2016.03.049

Matt McCauley, MD

Assistant Professor, Division of Critical Care

UW BerbeeWalsh Department of Emergency Medicine

Associate Medical Director

UW Organ and Tissue Donation

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Patton, C. Kilbane, K. (2024, Apr 15). Accidental Tracheostomy Decannulation. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by McCauley, M]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/tracheostomy-decannulation

Other Posts You May Enjoy