Written by: Alexandra Franiek, MD (NUEM ‘26) Edited by: Savannah Vogel, MD (NUEM ‘24)

Expert Commentary by: Matt Levine, MD

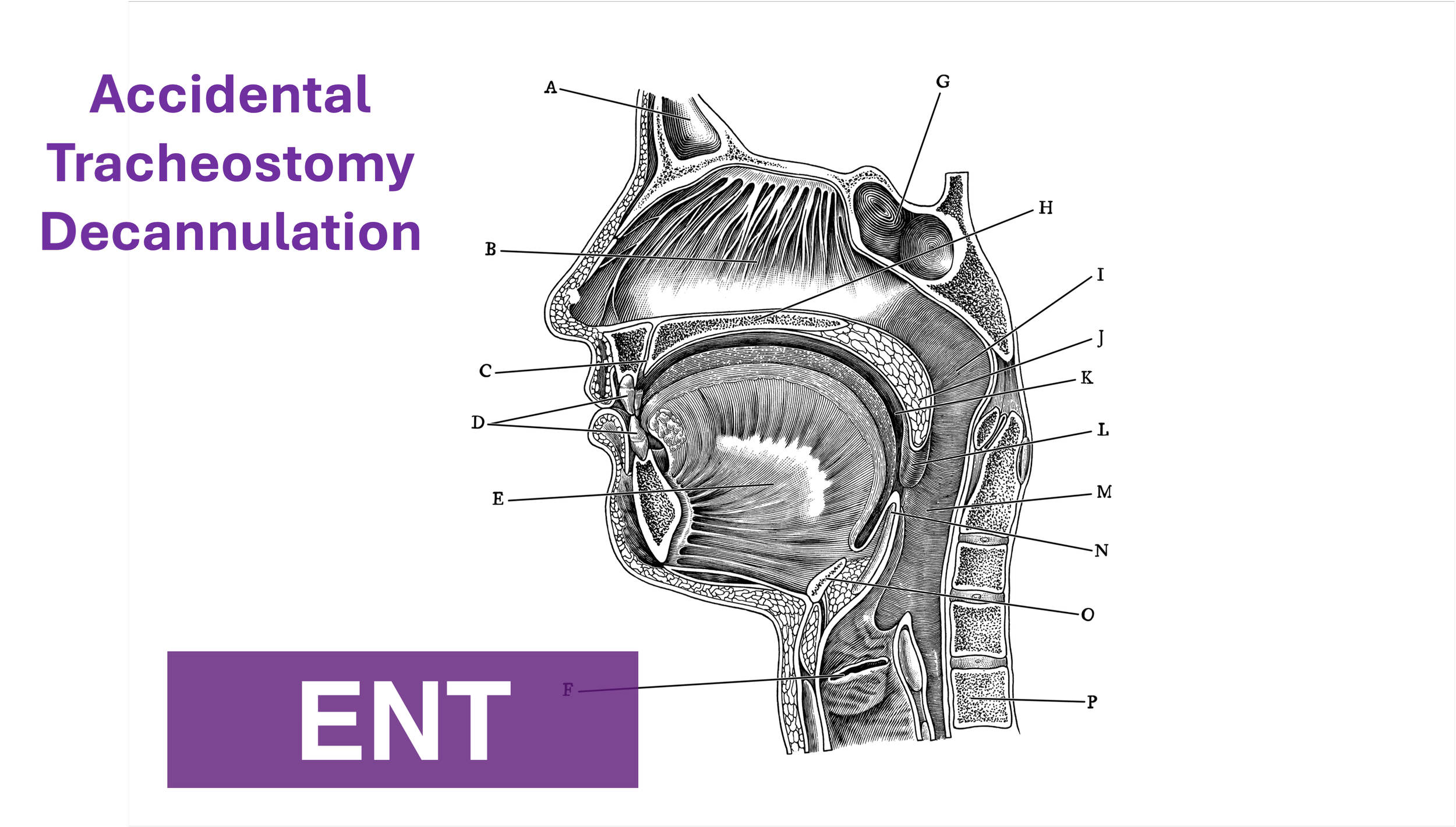

Frontal Bone

The frontal bone is composed of two “tables.” The posterior table is adherent to the dura mater. These fractures are often sustained during physical assault from a blunt object or MVCs (think unrestrained passenger). They require substantial force due to bone thickness and should always raise suspicion for neurological injury. The majority of patients will be unconscious on initial evaluation [1, 2].

https://coreem.net/core/facial-fractures/

Diagnosis

Inspect for overlying lacerations.

Crepitus may be palpable in sinus involvement.

Rhinorrhea may indicate cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage from damage to the cribriform plate. Halo test is performed by placing a fluid sample on a towel or gauze (sometimes this can be seen inadvertently on the bedsheet) – this is not specific and not always practical. Samples should be taken to test for glucose or b-2 transferrin for confirmation [3].

The gold standard diagnosis is CT imaging which should include scans of the face, brain and cervical spine [2].

Management

For through-and-through fractures, operative repair is necessary. As dura mater is connected to posterior table, complications include pneumocephalus, CSF leak and infectious spread.

Depressed fractures also require operative repair and IV antibiotics.

Isolated anterior table fractures are safe for discharge with nasal decongestants and facial surgery follow up. However, more than half of patients ultimately require surgical intervention [4].

Orbit

The orbit is made of seven bones which form four “walls.” 1. Frontal bone (superior wall), 2. Zygoma and sphenoid bones (lateral wall), zygoma and maxilla (inferior wall), lamina papyracea of the ethmoid bone and lacrimal bone (medial wall).

Classification

Blow out fractures are the most common fracture pattern. These are isolated to the inferior and/or medial walls. These occur when force transmitted through the globe fractures the relatively weak walls. Adipose tissue, the inferior rectus or inferior oblique muscle can herniate through the fracture site and enter the maxillary or ethmoid sinus.

Orbital fractures involve the orbital rim (and may also involve the walls).

Closed door fractures are non-displaced fractures.

Blow-in fractures are inwardly displaced fractures of the frontal or maxillary bones.

Trap door fractures are when orbital contents herniate through fractured bone and become entrapped as the bones return to anatomical position [1, 5].

Diagnosis

Detailed eye exam (one third of orbital wall fractures have associated ocular injury)

Visual acuity, pupillary exam, slit lamp exam, ocular pressure measurement

Tear drop pupil – think globe rupture

Enophthalmos from displacement of the globe precedes edema

Proptosis – think retrobulbar hematoma

Step off deformity and crepitus (as aforementioned, crepitus suggests sinus involvement)

Infraorbital region paraesthesia (in the distribution of the Maxillary branch of Trigeminal nerve) suggests an orbital floor fracture

Diplopia or upward gaze restriction from entrapment of the inferior rectus or inferior oblique

Gold standard diagnosis is facial and orbital CT, facial xray has extremely limited utility and is typically note indicated.

Management

When ocular involvement is suspected, an emergent ophthalmology consult is warranted. Intra-orbital swelling can precede ocular compartment syndrome and subsequent ischemic optic neuropathy.

If there is confirmed or suspected globe rupture or laceration, defer further examination, cover the eye (without applying pressure to the orbit) and consult ophthalmology.

Isolated orbital fractures are treated with sinus precautions (avoid nose blowing, coughing, straining). While the utility of prophylactic antibiotics is disputed, a short course of oral antibiotics is the current practice [1, 4].

The zygoma is a component of the orbit though is often segregated when discussing facial fractures. Briefly, zygoma fractures seldom require emergent surgical intervention and – if isolated to the zygomatic arch – can be discharged with prompt facial surgery follow up [6].

References:

1. Boswell KA (2013) Management of Facial Fractures. Emerg Med Clin North Am 31:539–551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emc.2013.01.001

2. Hedayati; T, Amin DP (2020) Trauma to the Face. In: Tintinalli JE, Ma OJ, Yealy DM, et al (eds) Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine : a Comprehensive Study Guide, Ninth. New York : McGraw-Hill, New York

3. Malaty J (2021) Facial and skull fractures. In: Fracture Management for Primary Care and Emergency Medicine, Fourth. Amsterdam

4. Chukwulebe S, Hogrefe C (2019) The Diagnosis and Management of Facial Bone Fractures. Emerg Med Clin North Am 37:137–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emc.2018.09.012

5. Tsao J Orbital Blow-Out Fractures. In: Core EM. https://coreem.net/core/orbital-blow-out-fractures/. Accessed 15 Mar 2023

6. Sutton-Ramsey D Facial Fractures. In: Core EM. https://coreem.net/core/facial-fractures/. Accessed 15 Mar 2023

Expert Commentary

As I previously mentioned in part 1, there are 5 major or common facial fractures that Emergency Physicians need to be familiar with:

Le Fort

Mandible

Nose

Orbital blow out

ZMC (zygomataticomaxillary complex)

I’d like to add some pearls to the nice foundation Dr. Franiek has laid out.

Most facial fractures are managed nonoperatively. However, there are certain findings that often lead to operative management. Be on alert for:

Deformity

Malocclusion

Trismus

Proptosis/enophthalmos

Infraorbital nerve injury

Ocular entrapment

Diplopia

Imaging for facial fracture evaluation will almost always be CT scanning. As previously mentioned, there may be other options specific to evaluation of the mandible. Otherwise, plain films for facial fractures (i.e. Caldwell, Towne, Waters views) lack sensitivity and need CT scanning if positive anyway and are now relics of another era.

The most common orbital fracture is the “blow out fracture”. The mechanism is not a blow to the orbital bones. It is an impact to the globe itself, causing a transient increase in intraorbital pressure, leading to fracture of the thin inferior orbital wall (and often the even thinner medial orbital wall, or lamina papyracea - paper thin like papyrus). So when an inferior orbital wall fracture is diagnosed, there has been by definition a significant impact to the globe. That is why a careful eye exam is warranted in all of these injuries. On CT imaging, the fracture is best visualized on coronal views and downward displacement of bone and soft tissue into the maxillary sinus is often obvious. The radiologist may comment on entrapment. Entrapment, however, is a clinical diagnosis, not a radiographic diagnosis, so extraocular movements must be checked.

The other facial fracture worth mentioning is the ZMC fracture. We used to call this a tripod fracture, which was a misnomer because there are fractures through all four (not three) of the zygoma bone’s sutures. It involves the orbit, and the zygoma also overlies muscles of mastication. These fractures may be managed operatively for cosmetic purposes or if they cause problems with vision, eye movements, or trismus.

Matt Levine, MD

Emergency Medicine Physician, Northwestern Memorial Hospital

Associate Professor, Feinberg School of Medicine

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Franiek, A. Vogel, S. (2025, Apr 29). Facial Fractures: Midface and Mandible. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Levine, M]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/facial fractures-frontal-bone-and-orbit

Other Posts You May Enjoy