Learn tips from the pros for identifying cardiac tamponade without delay

Fascia Iliaca Block

Learn this helpful technique for pain control in lower extremity injuries

SonoPro Tips and Tricks for Peripheral IV Access

Learn tips from the pros for ultrasound-guided IV access

Sono Pro Tips and Tricks for Evaluation of Elevated Intracranial Pressure

Written by: Emma Greever (NUEM ’25) Edited by: Maurice Hajjar, MD (NUEM ’22)

Expert Commentary by: John Bailitz, MD

Welcome to the NUEM SonoPro Tips and Tricks Series where Local and National Sono Experts team up to take you scanning from good to great for a particular diagnosis or procedure.

For those new to the probe, we recommend first reviewing the basics in the incredible FOAMed Introduction to Bedside Ultrasound Book, 5 Minute Sono, and POCUS Atlas. Once you’ve got the basics beat, then read on to learn how to start scanning like a Pro!

Did You Know?

Ocular ultrasound is a quick procedure which can be done at the bedside to help differentiate between various ophthalmologic emergencies including retinal detachment, vitreous detachment, vitreous hemorrhage, lens detachment, and presence of foreign bodies. Indications for ocular ultrasound include eye pain, acute changes in vision, eye trauma, and suspicion of elevated intracranial pressure, or if there is swelling of periorbital tissue that inhibits direct visualization of the eye. The one absolute contraindication for ocular ultrasound is any suspicion for globe rupture, as placing any pressure on the globe can worsen extrusion of intraocular contents.

Ocular ultrasound can also be used to evaluate for elevated intracranial pressure (ICP). The optic nerve sheath communicates directly with the subarachnoid space. Cerebrospinal fluid flows between the intracranial space and orbit within the subarachnoid space; therefore, increased intracranial pressure is transmitted to the optic nerve sheath. Elevation of ICP is reflected by dilation of the optic nerve sheath. This can be quantified by measuring optic nerve sheath diameter (ONSD). Dilation of the optic nerve sheath often occurs with anterior bulging of the optic disc, seen as optic disc elevation (ODE) on ultrasound. Bulging of the optic disc is seen as papilledema on fundoscopic exam. Both ONSD and ODE measurements are ways to assess for elevated ICP.

If there is concern for elevated ICP, it is not always possible to do a dilated fundoscopic exam, invasive monitoring, or other imaging such as a CT. Point of care ultrasound (POCUS) allows for quick evaluation. Furthermore, POCUS allows for monitoring dynamic changes in ICP as doing serial fundoscopic exams and CTs is not feasible. It is also less invasive than other intra-cranial monitoring. When comparing ONSD (with a cut-off value of >5 mm) with findings of increased ICP on CT, sensitivity and specificity are 95.6% and 92.3%, respectively.

Beyond the emergency department, where else can a SonoPro scan for increased ICP?:

Aside from patients in the emergency department, POCUS for elevated ICP can be used in critically ill children in the PICU, adults in the Neurocritical ICU, and on the battlefield with handheld ultrasounds in combat medicine. ONSD changes within minutes of ICP changing. Studies have demonstrated that the change in ONSD or ODE is strongly correlated with changes in ICP, implying that POCUS could be used to dynamically detect real-time changes in ICP. In neuro-critically ill children, POCUS cannot replace invasive ICP monitoring but can be used as a screening tool in the ICU for intermittent monitoring of ICP when invasive methods are unavailable. It can allow for accurate dynamic evaluation of ICP, which is important in children with traumatic brain injury as fluctuations are common. Additionally, POCUS can be used in many different environments in which imaging is not readily available, such as on the battlefield or in-flight.

How to scan like a Pro:

Place the head of the bed at 45 degrees.

Apply a large, waterproof transparent film dressing (such as a Tegaderm) over the eye you are going to ultrasound, making sure the eye is closed. Make sure to get as much air out from under the Tegaderm as you can.

Apply a large amount of water-soluble ultrasound gel on top of the dressing.

Using a high-frequency linear probe set to ocular mode, place the probe over the eye with the indicator to the patient’s right. It is important to use very minimal pressure on the eye. To have control over the probe and to be able to make small movements with minimal pressure on the eye, rest the side of your hand on the patient’s cheek or bridge of the nose to stabilize your hand.

Ensure the probe is oriented in the transverse plane.

Tell the patient to look straight forward, to the left or right, up, or down as needed to obtain the best view.

Be sure to scan both eyes when concerned for elevated ICP.

What to Look For:

Identify the following structures: anterior chamber, lens, vitreous, retina, and optic nerve.

Use the rule of 3x5 to measure optic nerve sheath diameter:

Find the posterior aspect of the globe overlying the optic nerve

From that point measure 3 mm posteriorly (point A)

Maximal sheath distension occurs at 3 mm behind the papilla

Measure the diameter of the optic nerve from the second point (point B, 3 mm deep)

Measure from outer wall to outer wall

< 5mm is normal, 5-6 mm is indeterminate, >6 mm is elevated

Assess for papilledema – measure optic disc elevation (ODE)

Measure area between the fundus and dome of the papilla

ODE >0.6 mm predicts presence of fundoscopic optic disc edema (sensitivity 82%, specificity 76%); if using the threshold of 1.00 mm then sensitivity is 73% and specificity 100%

This sign can take a couple days to develop and may not appear at the same time as elevated ocular disc diameter

How to interpret:

Determine if ICP is elevated:

< 5 mm = Likely normal ICP

>6 mm = Indicates elevated ICP

Many causes of this, next steps are to identify what is causing the elevation in ICP

5-6 mm = Indeterminate range

If elevated, further evaluation for etiology of elevated ICP and treatment of cause.

If indeterminate, assessing for papilledema by measuring the ODE can help in the indeterminate range, although absence of papilledema does not indicate normal ICP.

It is important to note that there is significant variation from person to person regarding ONSD. In other words, >6 mm does not necessarily indicate increased diameter and <5mm does not necessarily mean normal. The SonoPro must use clinical judgement while assessing the ONSD.

Where to Learn More (References)

Where to Learn More (Hyperlinked References):

https://coreem.net/core/ocular-ultrasound/

https://www.coreultrasound.com/onsd/

https://emcrit.org/pulmcrit/pulmcrit-algorithm-diagnosing-icp-elevation-ocular-sonography/

1. Lin JJ, Chen AE, Lin EE, Hsia SH, Chiang MC, Lin KL. Point-of-care ultrasound of optic nerve sheath diameter to detect intracranial pressure in neurocritically ill children - A narrative review. Biomed J. 2020;43(3):231-239. doi:10.1016/j.bj.2020.04.006

2. Richards E, Mathew D. Optic Nerve Sheath Ultrasound. [Updated 2021 Jul 31]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554479/

3. Teismann N, Lenaghan P, Nolan R, Stein J, Green A. Point-of-care ocular ultrasound to detect optic disc swelling. Acad Emerg Med. 2013 Sep;20(9):920-5. doi: 10.1111/acem.12206. PMID: 24050798.

Expert Commentary

Thank you for providing this outstanding NUEM Blog Post! Ocular ultrasound for ICP has been a hot topic for over a decade in the EM, PEM, and ICU POCUS literature.

For a full review of my approach to ocular ultrasound, please refer to our 2018 Post - Ocular Ultrasound: From Floaters to Fogginess!

Since that post ,additional literature has been posted questioning the need for Tegaderms over the eye for the reasons we discussed in 2018. Bottomline, if the patient is reliable and can keep their eyes closed for five minutes, then you can skip the Tegaderm. But when the patient is less reliable, then the extra step may still make sense. When locating and measuring the Optic Nerve Sheath (ONS), be absolutely sure to stabilize your hand on the patient's face or forehead particularly when you are over-caffeinated or tired. Then be careful to rock the probe about 15 degrees laterally (illustrated here) to visualize the ONS parallel to the probe’s center US beams, and thereby avoid any edge artifact from visualizing at an angle. Even with the best technique, our local teaching, clinical use, and pilot research has consistently confirmed the need for obtaining multiple measurements of the small optic nerve sheath. Then averaging the best three to obtain the most accurate measurement.

Thank You Dr. Greever (NUEM ’25) and Dr. Hajjar, MD (NUEM ’22) for helping to improve patient care and MedEd through POCUS! Happy scanning everyone.

John Bailitz, MD

Vice Chair for Academics, Department of Emergency Medicine

Professor of Emergency Medicine, Feinberg School of Medicine

Northwestern Memorial Hospital

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Greever, E. Hajjar, M. (2024, Sep 11). Sono Pro Tips and Tricks for Evaluation of Elevated Intracranial Pressure. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Bailitz, J]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/sonopro-tips-and-tricks-for-evaluation-of-elevated-intracranial-pressure

Other Posts You May Enjoy

Nephrolithiasis: Ultrasonography versus Computed Tomography

Written by: Kishan Ughreja , MD (NUEM ‘23) Edited by: Ade Akhentuamhen, MD (NUEM ‘21)

Expert Commentary by: Tim Loftus, MD, MBA

Journal Club: Ultrasonography versus Computed Tomography for Suspected Nephrolithiasis

A 70-year-old man with BPH s/p TURP, hypertension, hyperlipidemia and stroke presents to the ED with acute onset of intermittent sharp left flank pain radiating into the groin that awoke him from sleep. He endorses nausea without vomiting and denies fever. He also endorses slightly decreased urination with “dribbling.” His urinalysis shows >100 RBC and no signs of infection. Nephrolithiasis is likely high on your differential diagnosis. How do you proceed?

What is your initial imaging test of choice, ultrasound (US) or non-contrast CT, and why?

Would you be satisfied with only US and no follow-up CT?

Would you be confident in a point-of-care-ultrasound evaluation or a formal ultrasound?

Do outcomes for patients with suspected nephrolithiasis differ based on the initial imaging?

Should your medical decision-making change if the patient has a history of nephrolithiasis?

What would you do if the same patient presented again with persistent pain from a previously diagnosed stone?

Pain from suspected nephrolithiasis is a very common complaint in the ED and the incidence of the disease continues to increase. The estimated incidence over the past two decades is up to 340 visits per 100,000 individuals.1 Low-dose non-contrast abdominal CT has become the gold standard for diagnosis as it has become readily available in emergency departments nationwide, with some studies touting sensitivity and specificity of 97% and 95%, respectively.2 However, low dose CT still exposes the patient to radiation and may increase their risk of cancer, as many nephrolithiasis patients often undergo repeat imaging because of recurring pain or urological intervention. Additionally, CT scans prolong average ED lengths of stay. However, with ultrasonography becoming more prevalent in EDs, it may be possible that initial imaging may avoid this radiation risk and still have similar outcomes for patients. Let’s analyze this NEJM article comparing US to CT for the assessment of nephrolithiasis.

Study design: a multicenter, pragmatic, randomized comparative effectiveness trial

Population

N = 2759

ages 18- 76 yo

reported flank or abdominal pain that the treating physician wished to order imaging to establish or rule out a primary diagnosis of nephrolithiasis

not considered at high risk for serious alternative diagnoses e.g. cholecystitis, appendicitis, aortic aneurysm, or bowel disorders

no pregnant patients

no men >129 kg, no women >113 kg

no history of single kidney, renal transplantation, undergoing dialysis

Patient selection

Intervention protocol

patients randomized to 3 groups each using a different initial imaging modality (POCUS vs. Radiology US vs. CT)

patients contacted at 3, 7, 30, 90, and 180 days after randomization to assess study outcomes

Outcome measures

Primary Outcomes

high-risk diagnoses with complications that could be related to missed or delayed diagnoses — within 30 days of ED visit, including:

AAA w/rupture, PNA w/sepsis, appendicitis w/rupture, diverticulitis w/abscess or sepsis, bowel ischemia or perforation, renal infarction, renal stone w/abscess, pyelonephritis w/urosepsis or bacteremia, ovarian torsion w/necrosis, aortic dissection w/ischemia

cumulative radiation exposure from all imaging within 6 months after randomization

total cost (not reported in this study, ongoing analysis)

Secondary Outcomes

serious adverse events (FDA definition)

serious adverse events related to study participation

delayed diagnosis, like acute cholecystitis, appendicitis, bowel obstruction

return ED visits

hospitalizations after being discharged from ED

self-reported pain scores

diagnostic accuracy for nephrolithiasis

by comparing ED diagnosis at discharge to reference standard of confirmed stone by patient’s observation of passage or report of surgical removal

Results

no significant differences among groups in terms of pain scores, medical history, physical exam findings, and ED physician’s assessment of the likelihood of other diagnoses (Table 2)

POCUS and US groups had significantly lower cumulative radiation exposure over 6 months than the CT group (difference attributed to initial ED visit’s imaging choice)

11 patients (0.4%) had high risk diagnoses with complications during first 30 days after randomization, with no significant difference among the 3 groups

no difference when stratified by patients with a history of nephrolithiasis

no significant difference among groups in the number of patients with serious adverse events; total of 466 SAE in 316 patients (91.4% were hospitalizations during f/u period; 26.4% involved surgical treatment of complications of nephrolithiasis)

5 reported deaths (occurred between 38 and 174 days after randomization) — none thought to be related to study participation

the proportion of patients with a confirmed stone diagnosis within 6 months was similar in all 3 groups (POCUS 34.5% vs. US 31.2% vs. 32.7% CT)

diagnostic accuracy based on result of initial imaging modality

POCUS sensitivity 54% [48 - 60]; specificity 71% [67 - 75]

US sensitivity 57% [51 - 64]; specificity 73% [69 - 77]

CT sensitivity 88% [84 - 92]; specificity 58% [55 - 62]

Interpretation

The US group was exposed to less radiation than the CT group and had no significant differences in the incidence of high-risk diagnoses with complications, total serious adverse events, or related serious adverse events.

There also were no significant differences in pain scores, hospitalizations, ED readmissions among the groups.

Many patients in the ultrasound groups did get additional imaging, but this was not the majority.

Patients with a history of nephrolithiasis were less likely to undergo additional imaging with CT if they already had an ultrasound first (31% vs 36%). They did not have poorer outcomes than patients without a history of nephrolithiasis.

Patients only undergoing POCUS and no other testing had a significantly shorter ED stay (1.3 hours)

It is safe to pursue ultrasound as the initial imaging of choice for suspected nephrolithiasis (with additional imaging ordered as necessary at clinical discretion), though it should not necessarily be the only testing performed.

Strengths

large size, diversity in ED settings, randomized design, assessment of clinically important outcomes, a high follow-up rate

Weaknesses

no blinding of investigators, physicians, or patients as this was a pragmatic trial design

independent review was used to characterize serious adverse events related to study participation

strict reference standard for stone diagnosis which was unbiased, but prone to error based on the patient’s memory of self-reporting of stone passage

Internal/external validity

Given the aforementioned strengths of this study and its pragmatic design, these findings appear both internally and externally valid and may be applied to daily clinical practice

Take-Home Points

What is your initial imaging test of choice, ultrasound (US) or non-contrast CT, and why?

Ultrasound is a good choice for initial imaging as most patients do not end up requiring additional imaging during their visit. This leads to reduced cumulative radiation exposure.

Would you be satisfied with only US and no follow-up CT?

In this study, 40.7% of those in the POCUS group and 27% in the formal ultrasound group underwent subsequent CT. Follow up CT should depend on the patient and ultrasound operator. Keep in mind that this study excluded patients with kidney disease, pregnant patients, and obese patients. They also excluded patients who were high risk for other pelvic and abdominal diseases. Lastly the POCUS operators were ED physicians with training “recommended by ACEP.”

Would you be confident in a point-of-care-ultrasound evaluation compared to a formal ultrasound?

Yes. Sensitivity and specificity between these groups were similar.

Do outcomes for patients with suspected nephrolithiasis differ based on the initial imaging?

No. There was no significant difference in subsequent adverse events, pain, return visits or hospitalizations, or delayed diagnoses of other serious conditions.

Should your medical decision-making change if the patient has a history of nephrolithiasis?

In this study, patients with a history of nephrolithiasis were less likely to undergo additional imaging with CT if they already had an ultrasound first. They did not have poorer outcomes than patients without a history of nephrolithiasis. This suggests that it is safe to avoid ordering a CT in patients with recurrent stones.

What would you do if the same patient presented again with persistent pain from a previously diagnosed stone?

The majority of patients with adverse outcomes were due to infectious causes. Consider alternative diagnoses such as pyelonephritis. Additionally, although rare, renal infarct can present with acute flank pain and is diagnosed with a contrast CT.

References

Fwu, C. W., Eggers, P. W., Kimmel, P. L., Kusek, J. W., & Kirkali, Z. (2013). Emergency department visits, use of imaging, and drugs for urolithiasis have increased in the United States. Kidney international, 83(3), 479-486.

Coursey, C. A., Casalino, D. D., Remer, E. M., Arellano, R. S., Bishoff, J. T., Dighe, M., ... & Leyendecker, J. R. (2012). ACR Appropriateness Criteria® acute onset flank pain–suspicion of stone disease. Ultrasound quarterly, 28(3), 227-233.

Smith-Bindman, R., Aubin, C., Bailitz, J., Bengiamin, R. N., Camargo Jr, C. A., Corbo, J., ... & Kang, T. L. (2014). Ultrasonography versus computed tomography for suspected nephrolithiasis. New England Journal of Medicine, 371(12), 1100-1110.

Expert Commentary

Thank you very much to Dr.’s Ughreja and Akhetuamhen for an excellent blog post on a very relevant clinical topic. This is a great summary of the landmark randomized trial published in NEJM in 2014 assessing CT vs two types of US for patients with suspected renal colic in the ED setting. It is worth mentioning that this study was a multicenter study based in the US with representation from ED, Radiology, and Urology. The above study was well summarized and bears repeating that, in this multicenter randomized study assessing CT vs POCUS vs radiology performed US in patients with suspected renal colic in the ED setting, initial US reduced radiation exposure without adversely affecting patient-centered outcomes. It is worth mentioning several additional considerations and placing emphasis on others elucidated from this journal club review.

First, a subsequent systematic review (1) incorporating multispecialty (ED, Radiology, Urology) expert panel consensus recommendations has reiterated that in younger patients without a high suspicion for alternative diagnoses or complicating features of nephroureterolithiasis (such as fever, pyelonephritis, solitary kidney, dialysis, etc), US should be the initial diagnostic imaging modality of choice, if any. It's a great paper, worth reading (and appreciating who the authors are), and worth recalling for bedside teaching to junior learners in the ED.

Additionally, this paper brings to mind my second point, and something that is worth shouting from the hilltops -- a kidney stone is a clinical diagnosis! Now, of course, this is exclusive of those patients with high-risk or complicating features (e.g. pediatrics, pregnancy, solitary kidney, fever, unstable/critically ill, unrelenting pain, atypical features, etc). You don’t need any imaging to tell you the diagnosis in the vast majority of patients. US or CT are helpful in confirming the diagnosis when there is uncertainty or non-trivial pretest probability of alternative diagnoses, excluding alternative diagnoses, and identifying exact stone location and size, which can be used to help counsel patients at the bedside regarding the anticipated clinical course and next steps in management.

Third, for those with proper training, and with some exceptions (see the systematic review paper for case vignettes that highlight these), POCUS is non-inferior to radiology-performed US. And, it's not a “formal” US. I can’t remember the last time I attended a black-tie ultrasonography session, but that's just me.

Fourth, it's worth mentioning that although CT use can lead to the identification of incidental findings more commonly than US, identification of these incidental findings still happens rather often with POCUS (a common example is a renal cyst). Please ensure that you document and discuss with the patient accordingly.

Finally, a burden on us as EM clinicians is training in and awareness of clinical practice guidelines and recommendations from specialties outside of EM. As it relates to the diagnostic evaluation of suspected renal colic in the ED setting, the Choosing Wisely recommendations endorsed by the AUA are worth perusing as are the European/EUA guidelines, both of which suggest US as the initial diagnostic imaging modality of choice, for pediatric (CW) and non-high-risk patients without complicating features (EUA).

The bottom line is that CT is helpful for older patients or those in whom you are less sure about the diagnosis of renal colic. For younger or low-risk patients, suspected renal colic is a clinical diagnosis and often needs no imaging, but ultrasound would be an evidence-based first step. Thanks again toDr.’s Ughreja and Akhetuamhen.

References

1) Moore et al. Imaging in suspected renal colic: a systematic review of the literature and multispecialty consensus. J Urol 2019. 202(3):475-483.

Tim Loftus, MD, MBA

Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine

Fellowship Director of the Clinical Operations and Administration Fellowship Program, Northwestern Department of Emergency Medicine

Medical Director of Emergency Services Northwestern Lake Forest Hospital and Grayslake Emergency Center

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Ughreja, K. Akhentuamhen, A. (2022, May 16). Journal Club: Ultrasonography versus Computed Tomography for Suspected Nephrolithiasis. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Loftus, T]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/nephrolithiasis-ultrasonography-versus-computed-tomography.

Other Posts You May Enjoy

Hip Pain in Pediatrics

Written by: Tommy Ng, MD (NUEM ‘24) Edited by: Patricia Bigach, MD (NUEM ‘22) Expert review by: Terese Whipple, MD '20

So your kid won’t walk

One of the most common complaints in a pediatric Emergency Department is a child refusing or inability to ambulate. For normal development, a child is typically able to stand at 9 months, walk at 12 months, and run at 18 months. There is a certain degree of variability for these age constraints however any acute decrease in mobility should prompt an evaluation. A limp is defined as any abnormality in gait caused by pain, weakness, or deformity [1]. There are a plethora of conditions that can manifest with an antalgic gait or refusal to bear weight and it may be difficult to distinguish between etiologies given a child’s age.

History and physical

Age is an important factor as certain conditions are more likely depending on the patient’s age

Acuity should be determined as the chronicity of limp as certain etiologies are more acute while others are indolent. Additionally, certain infectious etiologies are more likely to present acutely or chronically.

Fever may suggest an infectious or rheumatologic cause

Trauma can help distinguish soft tissue vs orthopedic injuries

Past medical history is important to be focused on recent illnesses, antibiotic use, history of sickle cell disease, or hormonal diseases.

Physical examination should always include an attempt to ambulate the child unless there is an obvious contraindication noted immediately (eg open fracture). If the child refuses to bear weight, the child should be made non-weight bearing until serious pathology which can be worsened by walking is ruled out. Strength and range of motion of both lower extremities should also be examined [2].

Normal gait cycle (orthobullets.com)

Differential: the bad, the worse, and the ugly

Infectious

Transient Synovitis - Relatively common with a lifetime risk of 3%. Affects ages 3-8, males to females 2:1 [3]. Typically well appearing with normal labs, however, this is a diagnosis of exclusion and a septic joint should be ruled out. Management includes NSAID use and return to activity as tolerated [4].

Septic Arthritis - A “do not miss” diagnosis, commonly ages 3-6 with a slight male predominance [5]. Typically presenting with fevers and abnormal labs. The Kocher Criteria (originally developed in 1999 and validated in 2004) can be helpful in determining the likelihood of septic arthritis [6]. Management includes imaging studies, typical ultrasound to assess for a joint effusion, then a diagnostic arthrocentesis & antibiotics. The antibiotic regimen should be tailored to the child’s age and other predisposing factors to certain pathogens.

Osteomyelitis - Occurs in 1:5000-7700 kids in increased prevalence with MRSA communities; 2:1 male to female predominance with half of all cases occurring in ages less than 5 [7]. Commonly hematogenous spread from bacteremia; clinical suspicion should prompt radiologic evaluation. X-rays may be likely to be normal/inconclusive early in the disease course and MRI may be often indicated. Labs can be helpful but are not specific; a systematic review of >12,000 patients showed that elevated WBC was only present in 36% of patients [7]. ESR and CRP are non-specific but have a sensitivity of 95% [7]. Antibiotic therapy guidelines are similar to the management of septic arthritis. Surgical intervention may be indicated if there is a lack of improvement after 48-72 hours [8].

Osteomyelitis of the distal tibia (orthobullets.com)

Orthopedic

Legg-Calve-Perthes / Avascular Necrosis of the Hip - Age range 3-12 with a peak at 5-7, male to female ratio 3:1, can be bilateral in 10-20% of patients [9]. Radiographs should be obtained with high clinical suspicion but are often normal early in the course. An MRI would show fragmentation of the femoral head. The patient should be made non-weight bearing and be referred to a specialist. Children under 8 typically have a better prognosis however long-term management is poorly defined as there has been no long-term study [10].

Avascular necrosis of bilateral hip (orthobullets.com)

SCFE of left hip (orthobullets.com)

Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis - Typically obese child, median age 12, bilateral in 20-40% of cases [11]. Presentation is classically chronic hip pain with antalgic gait however may present with knee pain. Physical exam classically shows external rotation and abduction of the hip during hip flexion. Management is orthopedic consultation for operative stabilization [12].

References

Smith E, Anderson M, Foster H. The child with a limp: a symptom and not a diagnosis. Archives of disease in childhood - Education & practice edition. 2012;97(5):185-193. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2011-301245.

Naranje S, Kelly DM, Sawyer JR. A Systematic Approach to the Evaluation of a Limping Child. Am Fam Physician. 2015 Nov 15;92(10):908-16. PMID: 26554284.

Landin LA, Danielsson LG, Wattsgård C. Transient synovitis of the hip. Its incidence, epidemiology and relation to Perthes' disease. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1987;69(2):238-242.

Kermond S, Fink M, Graham K, Carlin JB, Barnett P. A randomized clinical trial: should the child with transient synovitis of the hip be treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs?. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;40(3):294-299. doi:10.1067/mem.2002.126171

Bennett OM, Namnyak SS. Acute septic arthritis of the hip joint in infancy and childhood. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;(281):123-132.

Kocher MS, Zurakowski D, Kasser JR. Differentiating between septic arthritis and transient synovitis of the hip in children: an evidence-based clinical prediction algorithm. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81(12):1662-1670. doi:10.2106/00004623-199912000-00002

Dartnell J, Ramachandran M, Katchburian M. Haematogenous acute and subacute paediatric osteomyelitis: a systematic review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(5):584-595. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.94B5.28523

Kaplan SL. Osteomyelitis in children. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2005;19(4):787-vii. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2005.07.006

Johansson T, Lindblad M, Bladh M, Josefsson A, Sydsjö G. Incidence of Perthes' disease in children born between 1973 and 1993. Acta Orthop. 2017;88(1):96-100. doi:10.1080/17453674.2016.1227055

Canavese F, Dimeglio A. Perthes' disease: prognosis in children under six years of age. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008 Jul;90(7):940-5. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B7.20691. PMID: 18591607.

Herngren B, Stenmarker M, Vavruch L, Hagglund G. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: a population-based study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18(1):304. Published 2017 Jul 18. doi:10.1186/s12891-017-1665-3

Reynolds RA. Diagnosis and treatment of slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Curr Opin Pediatr. 1999;11(1):80-83. doi:10.1097/00008480-199902000-00016

Expert Commentary

Thank you to Drs. Ng and Bigach for compiling a concise approach to a common chief complaint encountered by Emergency Physicians across the county: a child with a new limp or the refusal to bear weight.

The first step to this often-challenging problem is to try to localize the pain, and in non-verbal kiddos, this can be the most difficult task. As highlighted above, if the child is able, observe their ambulation and establish laterality of the limp and when it occurs during the gait cycle. Most of the disease processes we as Emergency Physicians are concerned about will cause an antalgic gait or a shortened stance phase. Shortening the stance phase decreases the amount of time that the child is bearing weight on the painful limb in an effort to decrease their pain. Sometimes this is so effective that their parents will observe a limp, but the child will not complain of any pain. A thorough exam of the back and lower extremities including inspection, palpation, and range of motion of all joints is also imperative for trying to localize the cause of their symptoms.

Let your exam and history guide lab evaluation and imaging, however, a good place to start is usually basic labs and inflammatory markers and a plain film of the affected joint. In some cases, you won’t be able to localize pain or exam findings at all, and a broad workup including plain film imaging of the entire extremity may be necessary.

A few additional pearls:

Always consider non-accidental trauma in children with new limp or refusal to bear weight.

Systemic symptoms such as fever should raise your suspicion for infectious etiology such as osteomyelitis or septic arthritis.

Classically children with transient synovitis will have had a recent viral illness, but this is not always the case.

Always examine the hips and consider hip plain films in children complaining of knee or thigh pain, but with a benign knee exam. They could be hiding an SCFE or Leg-Calve-Perthes disease.

Don’t forget to examine the SI joint, as it too can become infected or inflamed.

History of night pain should raise your antenna for malignancy like osteosarcoma, Ewing’s sarcoma, or leukemia.

Consider Lyme arthritis in your differential for joint pain and swelling in endemic areas.

Ultrasound can be useful when evaluating for septic arthritis and transient synovitis and can be performed at the bedside. However, both septic arthritis and transient synovitis can cause effusion, and therefore it is not useful in differentiating between the two. (That’s where the Kocher Criteria should be used to risk-stratify and determine if joint aspiration and fluid analysis are warranted)

Ultrasound evaluation of a pediatric hip joint demonstrating effusion courtesy of Dr. Maulik S Patel (https://radiopaedia.org)

Finally, make sure that the parents understand the diagnosis, expected course, and follow-up plan. If the child continues to refuse to bear weight, their symptoms worsen or do not improve, or they develop new concerning symptoms such as new fever or new urinary retention, they should return to the Emergency Department or their pediatrician for re-evaluation. More than once I’ve had patients who seemed for all the world to have transient synovitis eventually be diagnosed with spinal cord tumor, chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis, etc.

Terese Whipple, MD

Assistant Professor

Department of Emergency Medicine

University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Ng, T. Bigach, P. (2021, Dec 20). Hip Pain in Pediatrics. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Whipple, T]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/hippainpediatrics

Other Posts You May Enjoy

Sono Pro Tips and Tricks for Acute Appendicitis

Written by: Morgan McCarthy, MD (NUEM ‘24) Edited by: David Feiger, MD (NUEM ‘22)

Expert Commentary by: Shawn Luo, MD & John Bailitz, MD

Welcome to the NUEM SonoPro Tips and Tricks Series where Local and National Sono Experts team up to take you scanning from good to great for a particular diagnosis or procedure.

For those new to the probe, we recommend first reviewing the basics in the incredible FOAMed Introduction to Bedside Ultrasound Book, 5 Minute Sono, and POCUS Atlas. Once you’ve got the basics beat, then read on to learn how to start scanning like a Pro!

Did you know, appendicitis is one of the most common surgical emergencies. Despite this, some data suggests that appendicitis is missed in 3.8% to 15% of children and 5.9% to 23.5% of adults in ED visits. Appendicitis is difficult to diagnose due to the early nonspecific generalized symptoms (anorexia, generalized pain, nausea, diarrhea or constipation). We can use point of care ultrasound (POCUS) to help evaluate your differential diagnosis. One study showed that after only a 20-minute training ED physicians at various levels of experience were able to scan for appendicitis with a specificity of 97.9% and a sensitivity to 42.8%.

Beyond the classic pediatric patient, who else does the SonoPro scan?

Pocus use for appendicitis is one of the leading diagnostic tools in pediatrics for acute appendicitis. In the pediatric population limiting radiation is generally thought to be of utmost importance. The lack of exposure to radiation and small habitus makes ultrasound a great alternative in the pediatric patient. These tips and tricks can be useful in other high risk adult patients, like pregnant women. It is well known that in adults there is often a higher chance of pathology and surgeons are managing the ultimate say on whether more imaging is necessary. However, the use of ultrasound for acute appendicitis may save time, expedite care, lead to quicker consultation, and potentially augment patient satisfaction and improve outcomes.

How to scan like a Pro:

There are a few ways to scan for the appendix. To start, we recommend simply asking for the patient to point to where the pain is worst and place the probe directly over that spot.

A simple trick is to have the patient cross their right leg over their left leg; this brings the appendix closer to the abdominal wall.

If neither of these work, start to look for visual landmarks to orient yourself: iliac artery and vein, and the psoas muscle. The psoas muscle will be posterior, the iliac artery will be medial and the iliac crest lateral. Many times the appendix may be on top of the iliac artery. ‘Lawn mowing’ the probe up and down in this area may help it come into view.

What to Look For:

Try to look for a blind ending tubular structure that is not undergoing peristalsis. When you locate this, turn your probe to view the appendix in short axis and measure the anterior to posterior diameter. In a normal appendix this may be shorter than the lateral measurements as a normal appendix is compressible!

There are two main criteria for diagnosing appendicitis on ultrasound:

> 6mm*

non-compressible

*Note: Make sure to consider your patient’s age; the criteria may not apply to young children as their appendix may be naturally smaller. Appendix growth typically occurs at 3 to 6 years, therefore in this population you may depend more on secondary findings.

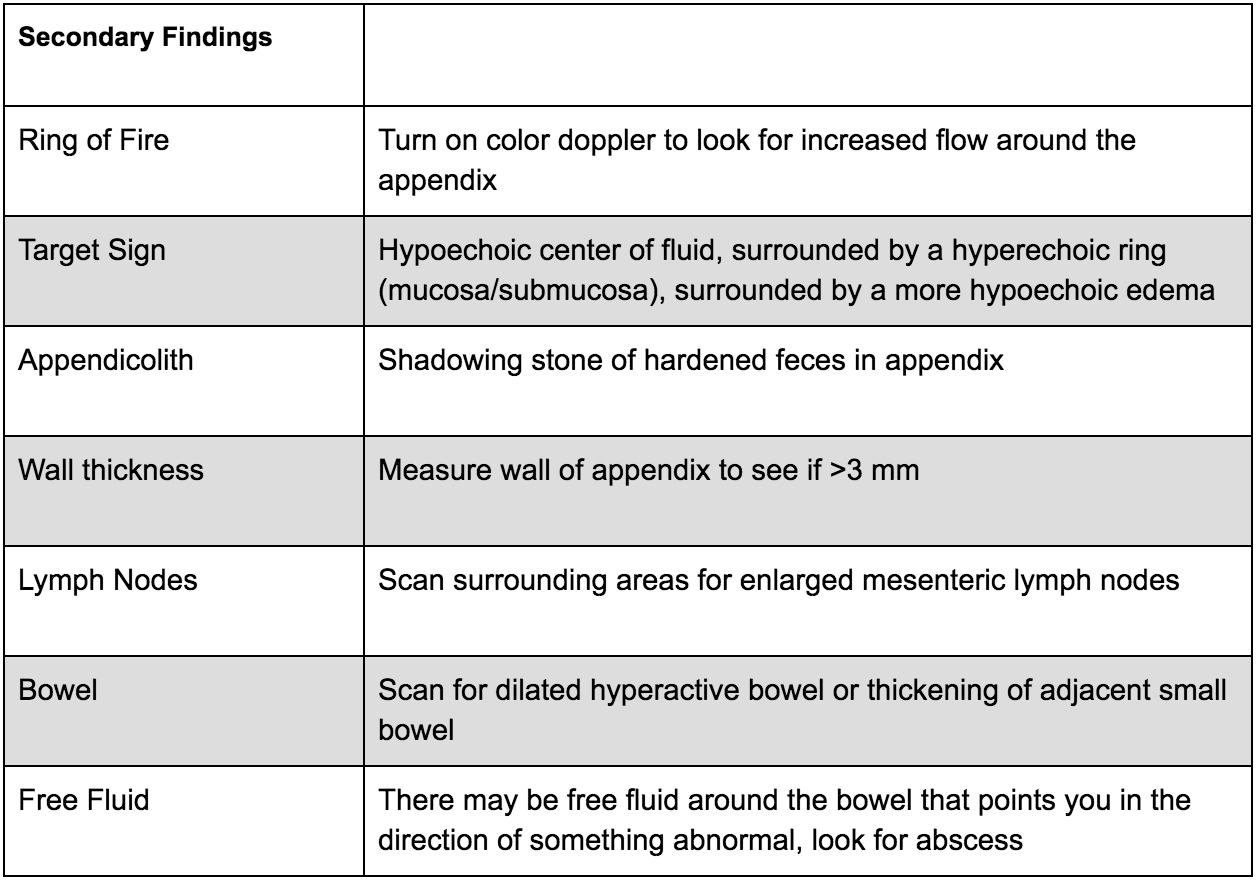

There are many secondary findings that many experts believe may be more useful than the measurements of the appendix itself as this can be very difficult to accurately measure:

What to do next:

Ultrasound for appendicitis is very specific, however not very sensitive. If you see a dilated non-compressible blind ending loop of bowel without peristalsis, you may have identified an appendicitis - call your surgeon, follow recommendations and start antibiotics! If you are uncertain, look for secondary signs of appendicitis as above; if they are found you can increase your suspicion of appendicitis. If these findings are not present, more advanced diagnostic imaging may be required with respect to your clinical suspicion. Consider an MRI in a young patient or CT scan with contrast in an adult for further evaluation.

Where to Learn More (References)

Mahajan P, Basu T, Pai C, et al. Factors Associated With Potentially Missed Diagnosis of Appendicitis in the Emergency Department. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(3):e200612. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.0612.

Ma, John, et al. Ma and Mateer's Emergency Ultrasound. McGraw-Hill Education, 2020.

Macias, Micheal. TPA, The Pocus Atlas.

Availa, Jacob. 5 minute Sono.

Nelson, Chiricolo, Raio, Theodoro, Patel, Johnson. Can Emergency Physicians Positively Predict Acute Appendicitis on Focused Right Lower Quadrant Ultrasound?. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 2005; 46: 27-28

Expert Commentary

Excellent job by Morgan and David on this engaging and informative post summarizing the latest and greatest pro-tips and tricks for POCUS for Appendicitis. POCUS again has been demonstrated to be a helpful adjunct to improve time to diagnosis and treatment when utilized by trained clinicians for appropriate patients. On your next pediatric, pregnant, or otherwise thin “Rule out Appy”, begin the exam by asking the patient to cross their leg to flex the psoas muscle to bring the appendix closer to probe. Have the patient point to the pain to identify where to start. If the appendix is not visualized, then go to McBurney’s point in the axial plane, visualizing the iliac artery & vein to find the nearby appendix. Next, start “lawn mowing” by compressing slowly but with adequate depth to displace bowel gas. Once you see what appears to be an inflamed appendix, trace the structure to verify the blind-ending and hold your probe for a few seconds to confirm the lack of peristalsis. Measure the diameter, then turn on color flow and look for other secondary signs of inflammation. Since the specificity is high, when appendicitis is visualized, call your surgeon, and consider skipping the CT. But remember, since the appendix often “hides” within the bowel the sensitivity is low, so other comprehensive imaging will be needed to reach the correct diagnosis.

John Bailitz, MD

Vice Chair for Academics, Department of Emergency Medicine

Professor of Emergency Medicine, Feinberg School of Medicine

Northwestern Memorial Hospital

Shawn Luo, MD

PGY4 Resident Physician

Northwestern University Emergency Medicine

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] McCarthy, M. Feiger, D. (2021, Nov 22). Sono Pro Tips and Tricks for Acute Appendicitis. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Luo, S and Bailitz, J]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/sonopro-tips-and-tricks-for-acute-appendicitis

Other Posts You May Enjoy

SonoPro Tips and Tricks for Aortic Aneurysm and Dissection

Written by: John Li, MD (NUEM ‘24) Edited by: Andra Farcas, MD (NUEM ‘21) Expert Commentary by: John Bailitz, MD & Shawn Luo, MD (NUEM ‘22)

SonoPro Tips and Tricks

Welcome to the NUEM Sono Pro Tips and Tricks Series where Sono Experts team up to take you scanning from good to great for a problem or procedure! For those new to the probe, we recommend first reviewing the basics in the incredible FOAMed Introduction to Bedside Ultrasound Book and 5 Minute Sono. Once you’ve got the basics beat, then read on to learn how to start scanning like a Pro!

Aortic ultrasound is a staple in emergency point of care ultrasound. It has incredible sensitivity (97.5-100%) and specificity (94.1-100%) in detecting abdominal aortic aneurysms and can provide a diagnosis for critically ill patients in seconds. [1-4] However, it can often be a technically difficult study for beginner sonographers due to shadowing bowel gas and patient body habitus. Follow along in this installment of our Sono Pro Tips and Tricks Series to become an expert in finding aortas!

Beyond the classic elderly male smoker with abdominal, flank, or back pain, what are other scenarios where you would use aortic ultrasound?

Older patients with limb ischemia - an aortic aneurysm can have atherosclerosis or a mural thrombus which can embolize and cause an arterial occlusion!

“But they fixed my aorta!” Aortic endograft leakage can sometimes present with symptoms that are similar to a AAA rupture, such as back pain, flank pain, or hemodynamic instability.

How to scan like a Pro

Always Start Smart: Aortic ultrasound can be tricky because of factors that seem out of our control, such as bowel gas or patient body habitus.

When scanning for an abdominal aortic aneurysm, start scanning in the epigastric region with a transverse view and apply constant pressure, gently pushing the bowel gas out of the way as you slide the probe down towards the patient’s feet.

Tell your patients to bend their knees! This relaxes the abdominal musculature and can help you move bowel gas or make better contact with the probe.

What if you still can’t see it? Try looking in the right upper quadrant view of the FAST exam!

Start with your probe in the right mix-axillary line and use the liver as your acoustic window. You may need to fan anteriorly or posteriorly depending on the patient’s body habitus and your positioning.

Unfortunately, this view predominantly visualizes the superior aspect of the abdominal aorta, and it can be difficult to visualize the inferior abdominal aorta or the bifurcation.

Here we are looking at a modified RUQ view, where the aorta is visualized on the bottom part of the screen using the liver as an acoustic window. (acep.org)

Pro Pickups!

What’s that weird aneurysm?

Most people are familiar with the classic fusiform aortic aneurysm, but saccular aneurysms can be easily missed because of shadowing bowel gas obstructing parts of the aorta. Saccular aneurysms actually have a higher risk of rupture and repair is recommended for smaller diameters.

Here you can see two images in the longitudinal axis of the different kinds of abdominal aortic aneurysms. On the left is a saccular aneurysm and on the right is a fusiform one. Be sure to pay attention to the mural thrombus in the walls of both of these aortas - they can embolize and cause arterial occlusions! (med.emory.edu)

2. How big is that aorta anyways?

Be sure to always measure the aorta from outside wall to outside wall!

Many aortic aneurysms have a mural thrombus or intraluminal clot, and it can be very easy to mistake these for extra-luminal contents.

Remember the concerning numbers: >5.5cm for men and >5cm for women!

What the Pros Do Next

Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

If the patient is hemodynamically unstable (defined as BP <90/60, altered mental status, or other signs of end-organ damage), go straight to the OR!

If the patient is hemodynamically stable (defined as the absence of any of the above), then the next step is to obtain further imaging, such as a CT Angiogram, which is the imaging gold standard.

If you are concerned about a large AAA that could be a contained leak but the patient is hemodynamically stable, then we recommend an emergent vascular surgery consult

If you find a small AAA (defined as <5cm in women or <5.5cm in men) that you do not think is actively contributing to the patient’s symptoms, then we recommend outpatient vascular surgery follow up

SonoPro Tips - Where to Learn More

Do you want to review more examples of pathologic images that you may see when you are doing an aortic ultrasound? Be sure to check out The Pocus Atlas by our expert editor Dr. Macias. Aortic pathology is quite rare, and going through these images will help immensely in recognizing this diagnosis in emergent situations. If you’re interested in looking at some of the evidence behind aortic ultrasound, be sure to check out the evidence atlas here as well.

References

Rubano E, Mehta N, Caputo W, Paladino L, Sinert R. Systematic review: emergency department bedside ultrasonography for diagnosing suspected abdominal aortic aneurysm. Acad Emerg Med. 2013 Feb;20(2):128-38. doi: 10.1111/acem.12080. PMID: 23406071.

Hunter-Behrend, Michelle, and Laleh Gharahbaghian. “American College of Emergency Physicians.” ACEP // Home Page, 2016, www.acep.org/how-we-serve/sections/emergency-ultrasound/news/february-2016/tips-and-tricks-big-red---the-aorta-and-how-to-improve-your-image/.

Ma, John, et al. Ma and Mateer's Emergency Ultrasound. McGraw-Hill Education, 2020.

Mallin, Mike, and Matthew Dawson. Introduction to Bedside Ultrasound: Volume 1. Emergency Ultrasound Solutions, 2013.

Macias, Michael. TPA, www.thepocusatlas.com/.

Expert Commentary

Another great Sono Pro Post! Thank you John Li and Andra for helping everyone move from good to great when scanning for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. As noted, this application defines Emergency Ultrasound as a fast (pun intended), accurate, and life saving diagnostic tool for every EM physicians tool belt. When consistent probe pressure does not do the trick, consider the RUQ view for a quick look. Since most AAA’s are fusiform, this may quickly confirm your suspicions and prompt the call to get the OR ready. Be sure to visualize the entire abdominal aorta throughout in both short and long axis to identify saccular aneurysms and even the rare aortic occlusion!

John Bailitz, MD

Vice Chair for Academics, Department of Emergency Medicine

Professor of Emergency Medicine, Feinberg School of Medicine

Northwestern Memorial Hospital

Shawn Luo, MD

PGY4 Resident Physician

Northwestern University Emergency Medicine

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Li, J. Farcas, A. (2021 Oct 11). SonoPro Tips and Tricks for Aortic Aneurysm. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Bailitz, J. Shawn, L.]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/sonopro-tips-and-tricks-for-aortic-aneurysm

Other Posts You May Enjoy

SonoPro Tips and Tricks for Pulmonary Embolism

Written by: Megan Chenworth, MD (NUEM ‘24) Edited by: Abiye Ibiebele, MD (NUEM ‘21) Expert Commentary by: John Bailitz, MD & Shawn Luo, MD (NUEM ‘22)

SonoPro Tips and Tricks

Welcome to the NUEM Sono Pro Tips and Tricks Series where Sono Experts team up to take you scanning from good to great for a problem or procedure! For those new to the probe, we recommend first reviewing the basics in the incredible FOAMed Introduction to Bedside Ultrasound Book and 5 Minute Sono. Once you’ve got the basics beat, then read on to learn how to start scanning like a Pro!

Did you know that focused transthoracic cardiac ultrasound (FOCUS) can help identify PE in tachycardic or hypotensive patients? (It has been shown to have a sensitivity of 92% for PE in patients with an HR>100 or SBP<90, and approaches 100% sensitivity in patients with an HR>110 [1]). Have a hemodynamically stable patient with PE and wondering how to risk stratify? FOCUS can identify right heart strain better than biomarkers or CT [2].

Who to FOCUS on?

Patients presenting with chest pain or dyspnea without a clear explanation, or with a clinical concern for PE. The classic scenario is a patient with pleuritic chest pain with VTE risk factors such as recent travel or surgery, systemic hormones, unilateral leg swelling, personal or family history of blood clots, or known hypercoagulable state (cancer, pregnancy, rheumatologic conditions).

Patients presenting with unexplained tachycardia or dyspnea with VTE risk factors

Unstable patients with undifferentiated shock

When PE is suspected but CT is not feasible: such as when the patient is too hemodynamically unstable to be moved to the scanner, too morbidly obese to fit on the scanner, or in resource-limited settings where scanners aren’t available

One may argue AKI would be another example of when CT is not feasible (though there is some debate over the risk of true contrast nephropathy - that is a discussion for another blog post!)

How to scan like a Pro

Key is to have the patient as supine as possible - this may be difficult in truly dyspneic patients

If difficulty obtaining views arise, the left lateral decubitus position helps bring the heart closer to the chest wall

FOCUS on these findings

You only need one to indicate the presence of right heart strain (RHS).

Right ventricular dilation

Septal flattening: Highly specific for PE (93%) in patients with tachycardia (HR>100) or hypotension (SBP<90) [1]

Tricuspid valve regurgitation

McConnell’s sign

Definition: Akinesis of mid free wall and hypercontractility of apical wall (example below)

The most specific component of FOCUS: 99% specific for patients with HR>100bpm or SBP<90 [1]

Tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE)

The most sensitive single component of FOCUS: TASPE < 2cm is 88% sensitive for PE in tachycardic and hypotensive patients; 93% sensitive when HR > 110 [1]

Where to FOCUS

Apical 4 Chamber (A4C) view: your best shot at seeing it all

Find the A4C view in the 5th intercostal space in the midclavicular line

Optimize your image by sliding up or down rib spaces, sliding more lateral towards the anterior axillary line until you see the apex with the classic 4 chambers - if the TV and MV are out of the plane, rotate the probe until you can see both openings in the same image; if the apex is not in the middle of the screen, slide the probe until the apex is in the middle of the screen. If you are having difficulty with this view, position the patient in the left lateral decubitus.

Important findings:

RV dilation: the normal RV: LV ratio in diastole is 0.6:1. If the RV > LV, it is abnormal. (see in the image below)

Septal flattening/bowing is best seen in this view

McConnell’s sign: akinesis of the free wall with preserved apical contractility

McConnell’s Sign showing akinesis of the free wall with preserved apical contractility

4. Tricuspid regurgitation can be seen with color flow doppler when positioned over the tricuspid valve

Tricuspid regurgitation seen with color doppler flow

5. TAPSE

Only quantitative measurement in FOCUS, making it the least user-dependent measurement of right heart strain [3]

A quantitative measure of how well the RV is squeezing. RV squeeze normally causes the tricuspid annulus to move towards the apex.

Fan to bring the RV as close to the center of the screen as possible

Using M-mode, position the cursor over the lateral tricuspid annulus (as below)

Activate M-mode, obtaining an image as below

Measure from peak to trough of the tracing of the lateral tricuspid annulus

Normal >2cm

How to measure TAPSE using ultrasound

Parasternal long axis (PSLA) view - a good second option if you can’t get A4C

Find the PSLA view in the 4th intercostal space along the sternal border

Optimize your image by sliding up, down, or move laterally through a rib space, by rocking your probe towards or away from the sternum, and by rotating your probe to get all aspects of the anatomy in the plane. The aortic valve and mitral valve should be in plane with each other.

Important findings:

RV dilation: the RV should be roughly the same size as the aorta and LA in this view with a 1:1:1 ratio. If RV>Ao/LA, this indicates RHS.

Septal flattening/bowing of the septum into the LV (though more likely seen in PSSA or A4C views)

Right heart strain demonstrated by right ventricle dilation

Parasternal Short Axis (PSSA) view: the second half of PSLA

Starting in the PSLA view, rotate your probe clockwise by 90 degrees to get PSSA

Optimize your image by fanning through the heart to find the papillary muscles - both papillary muscles should be in-plane - if they are not, rotate your probe to bring them both into view at the same time

Important findings:

Septal flattening/bowing: in PSSA, it is called the “D-sign”.

“D-sign” seen on parasternal short axis view. The LV looks like a “D” in this view, particularly in diastole.

Subxiphoid view: can add extra info to the FOCUS

Start just below the xiphoid process, pointing the probe up and towards the patient’s left shoulder

Optimize your image by sliding towards the patient’s right, using the liver as an echogenic window; rotate your probe so both MV and TV are in view in the same image

Important findings

Can see plethoric IVC if you fan down to IVC from RA (not part of FOCUS; it is sensitive but not specific to PE)

Plethoric IVC that is sensitive to PE

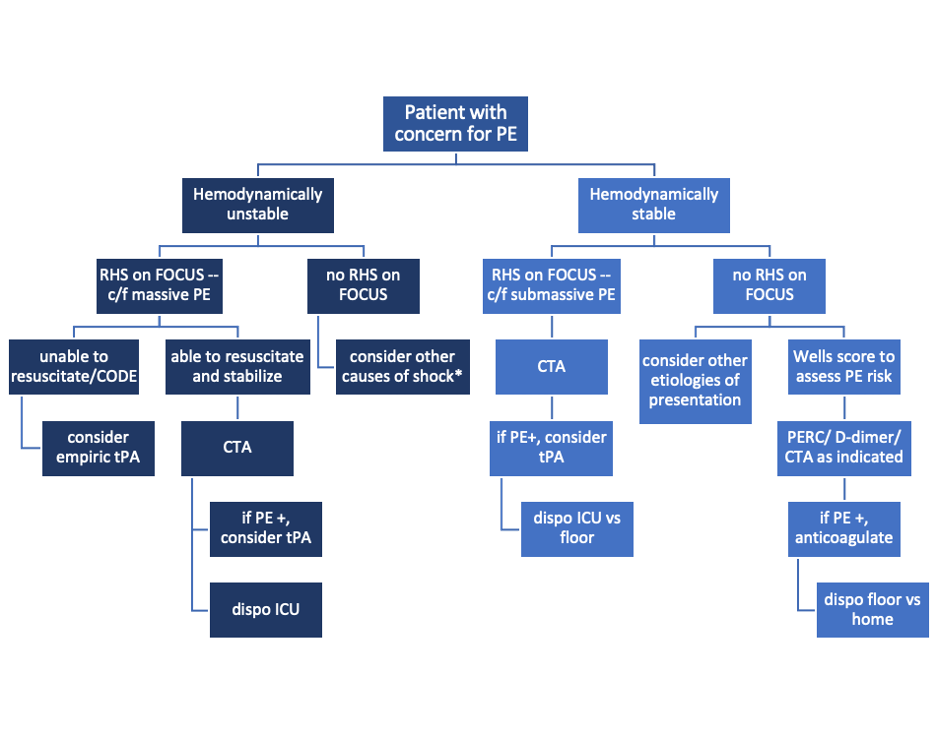

What to do next?

Sample algorithm for using FOCUS to assess patients with possible PE.

*cannot completely rule out PE, but negative FOCUS makes PE less likely

Limitations to keep in mind:

FOCUS is great at finding heart strain, but the lack of right heart strain does not rule out a pulmonary embolism

Systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that the overall sensitivity of FOCUS for PE is 53% (95% CI 45-61%) for all-comers [5]

Total FOCUS exam requires adequate PSLA, PSSA, and A4C views – be careful when interpreting inadequate scans

Can see similar findings in chronic RHS (pHTN, RHF)

Global thickening of RV (>5mm) can help distinguish chronic from acute RHS

McConell’’s sign is also highly specific for acute RHS, whereas chronic RV failure typically appears globally akinetic/hypokinetic

SonoPro Tips - Where to Learn More

Right Heart Strain at 5-Minute Sono: http://5minsono.com/rhs/

Ultrasound GEL for Sono Evidence: https://www.ultrasoundgel.org/posts/EJHu_SYvE4oBT4igNHGBrg, https://www.ultrasoundgel.org/posts/OOWIk1H2dePzf_behpaf-Q

The Pocus Atlas for real examples: https://www.thepocusatlas.com/echocardiography-2

The Evidence Atlas for Sono Evidence: https://www.thepocusatlas.com/ea-echo

References

Daley JI, Dwyer KH, Grunwald Z, Shaw DL, Stone MB, Schick A, Vrablik M, Kennedy Hall M, Hall J, Liteplo AS, Haney RM, Hun N, Liu R, Moore CL. Increased Sensitivity of Focused Cardiac Ultrasound for Pulmonary Embolism in Emergency Department Patients With Abnormal Vital Signs. Acad Emerg Med. 2019 Nov;26(11):1211-1220. doi: 10.1111/acem.13774. Epub 2019 Sep 27. PMID: 31562679.

Weekes AJ, Thacker G, Troha D, Johnson AK, Chanler-Berat J, Norton HJ, Runyon M. Diagnostic Accuracy of Right Ventricular Dysfunction Markers in Normotensive Emergency Department Patients With Acute Pulmonary Embolism. Ann Emerg Med. 2016 Sep;68(3):277-91. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.01.027. Epub 2016 Mar 11. PMID: 26973178.

Kopecna D, Briongos S, Castillo H, Moreno C, Recio M, Navas P, Lobo JL, Alonso-Gomez A, Obieta-Fresnedo I, Fernández-Golfin C, Zamorano JL, Jiménez D; PROTECT investigators. Interobserver reliability of echocardiography for prognostication of normotensive patients with pulmonary embolism. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2014 Aug 4;12:29. doi: 10.1186/1476-7120-12-29. PMID: 25092465; PMCID: PMC4126908.

Hugues T, Gibelin PP. Assessment of right ventricular function using echocardiographic speckle tracking of the tricuspid annular motion: comparison with cardiac magnetic resonance. Echocardiography. 2012 Mar;29(3):375; author reply 376. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2011.01625_1.x. PMID: 22432648.

Fields JM, Davis J, Girson L, et al. Transthoracic echocardiography for diagnosing pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2017;30:714–23.e4.

Expert Commentary

RV function is a frequently overlooked area on POCUS. Excellent post by Megan looking specifically at RV to identify hemodynamically significant PEs. We typically center our image around the LV, so pay particular attention to adjust your views so the RV is optimized. This may mean moving the footprint more laterally and angle more to the patient’s right on the A4C view. RV: LV ratio is often the first thing you will notice. When looking for a D-ring sign, make sure your PSSA is actually in the true short axis, as a diagonal cross-section may give you a false D-ring sign. TAPSE is a great surrogate for RV systolic function as RV contracts longitudinally. Many patients with pulmonary HTN or advanced chronic lung disease can have chronic RV failure, lack of global RV thickening. Lastly remember, that a positive McConnell’s sign is a great way to distinguish acute RHS from chronic RV failure.

John Bailitz, MD

Vice Chair for Academics, Department of Emergency Medicine

Professor of Emergency Medicine, Feinberg School of Medicine

Northwestern Memorial Hospital

Shawn Luo, MD

PGY4 Resident Physician

Northwestern University Emergency Medicine

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Chenworth, M. Ibiebele, A. (2021 Oct 4). SonoPro Tips and Tricks for Pulmonary Embolism. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Bailitz, J. Shawn, L.]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/sonopro-tips-and-tricks-for-pulmonary-embolism

Other Posts You May Enjoy

SonoPro Tips and Tricks for Pneumothroax

Written by: Morgan McCarthy, MD (NUEM ‘24) Edited by: Jon Hung, MD (NUEM ‘21) Expert Commentary by: John Bailitz, MD & Shawn Luo, MD (NUEM ‘22)

SonoPro Tips and Tricks

Welcome to the NUEM Sono Pro Tips and Tricks Series where Sono Experts team up to take you scanning from good to great for a problem or procedure! For those new to the probe, we recommend first reviewing the basics in the incredible FOAMed Introduction to Bedside Ultrasound Book and 5 Minute Sono. Once you’ve got the basics beat, then read on to learn how to start scanning like a Pro!

Did you know that Lung Ultrasound (LUS) has a higher sensitivity than the traditional upright anteroposterior chest X-ray for the detection of a pneumothorax? (LUS has a reported 90.9 for sensitivity and 98.2 for specificity. CXR were 50.2 for sensitivity and 99.4 for specificity). Busy trauma bay? Ultrasound is faster than calling for X-ray. Critically ill patient? Small pneumothoraces are less likely to be missed with ultrasound. To take your Sono Skills to the next level, read on:

Beyond the classic trauma patient during your E-Fast Exam, who else does the Sono-Pros scan?

Primary spontaneous pneumothorax: the classic scenario is a tall, young adult, with symptoms such as breathlessness, along with potentially those with risk factors of pneumothoraxes such as smoking, male sex, family history of pneumothorax

Secondary spontaneous pneumothorax: those with underlying lung disease including but not limited to COPD, tuberculosis, necrotizing pneumonia, pneumonocystis carini, lung cancer, sarcoma involving the lung, sarcoidosis, endometriosis, cystic fibrosis, acute severe asthma, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

Of course, traumatic pneumothorax, especially in penetrating trauma or blunt trauma with broken ribs

Don’t forget iatrogenic causes of pneumothorax including transthoracic needle aspiration, subclavian vessel puncture, thoracentesis, pleural biopsy, and mechanical ventilation

SonoPro Tips - How to scan like a Pro

The key is to have the patient completely supine - air rises! - with the probe in the anterior field in sagittal orientation pointing towards the patient's head.

It is commonly taught to start at the second intercostal space, midclavicular line, and scan down a few lung spaces to at least the 4th intercostal space, however, keep in mind some studies show that trauma supine trauma patients had pneumothoraces seen more commonly in the 5-8 rib spaces.

Important Landmarks

Green = Subcutaneous tissue. Red = Pleural space. Blue = A - lines.

4. Look for lung sliding, improve your image by turning down gain and decrease depth to have lung sliding become clearer

What to Look For:

To Rule-Out a pneumothorax

Lung Sliding - Lung sliding has a negative predictive value of 100% for ruling out a pneumothorax, however only at that interspace

Additional Findings: B-lines and Z lines also help to rule out pneumothorax!

2. To Rule-In a pneumothorax

Lung point - the interface between where lung sliding is happening and where the absence of lung sliding is happening has been shown to have 100% specificity for pneumothorax.

Keep in mind the border of where the heart and lung come in contact and the border where the diaphragm and lung come in contact can cause a false lung point.

The lung point may be hard to find in a larger pneumothorax, and impossible to find in a completely collapsed lung.

3. Next turn on M-mode:

Sandy Beach Shore = Lung sliding (left). Barcode Sign = No lung sliding (right)

What to do next:

Lung sliding = sensitive, Lung point = specific

If you see lung sliding, there is no pneumothorax

If you do not see lung sliding it does not rule in a pneumothorax -> look for a lung point, the interface between where lung sliding is happening and where the absence of lung sliding is happening to rule it in

Always keep in mind other causes that result in lack of lung sliding before management decisions take place!: atelectasis, main-stem intubation, adhesions, contusions, and arrest or apnea. Check out this great table from 5 - Min Sono.

4. If your patient is apneic or has a mainstem intubation look for lung pulse, when the heart beats if the parietal and visceral pleura are touching (no pneumothorax) it will show a pulse at the interfaces of the pleura

5. Sub-Q emphysema - Always look for E - lines. When there is subcutaneous air above the pleural line it creates a false pleural line above the actual pleural. You may also see B-lines obscuring the actual pleural line. This is most likely subcutaneous air and you can not interpret it for a pneumothorax.

SonoPro Tips - Where to Learn More

American College of Emergency Physicians. Emergency ultrasound imaging criteria compendium. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48(4):487-510.

Ma, John, et al. Ma and Mateer's Emergency Ultrasound. McGraw-Hill Education, 2020.

Macias, Micheal. TPA, The Pocus Atlas.

Availa, Jacob. 5 minute Sono.

Alrajhi K, Woo MY, Vaillancourt C. Test characteristics of ultrasonography for the detection of pneumothorax: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2012;141(3):703-708.

Expert Commentary

Morgan went “beyond lung sliding” and dove deep into how to increase your sensitivity & specificity for PTX with POCUS. Supine is ideal to make PTX visible against the anterior chest wall, but if the patient cannot tolerate lying flat, look at the apical pleural superior to the clavicles. First, identify the true pleural line--it should be the bright line just deep to the ribs in your view. SQ emphysema may obscure the view or even mimic the pleura, although its outline is usually more hazy & irregular, a little pressure helps to move the SQ air out of the way can be helpful. Sliding? Great, PTX ruled out. But absent sliding does not automatically mean PTX. Make sure there is no B-line or “lung pulse”, as sometimes pleural adhesion or poor ventilation can cause absent sliding too. Most of the time you don’t need M-mode unless the movement is very subtle and you want to be extra sure. The lung point is pathognomonic for PTX, but don’t waste time digging around for it if the patient is unstable with a good clinical story for PTX > decompress instead!

John Bailitz, MD

Vice Chair for Academics, Department of Emergency Medicine

Professor of Emergency Medicine, Feinberg School of Medicine

Northwestern Memorial Hospital

Shawn Luo, MD

PGY4 Resident Physician

Northwestern University Emergency Medicine

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] McCarthy, M. Hung J. (2021 Sept 20). SonoPro Tips and Tricks for Pneumothorax. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Bailitz, J. Shawn, L.]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/sonopro-tips-and-tricks-for-pneumothorax

Other Posts You May Enjoy

SonoPro Tips and Tricks for Acute Cholecystitis

Written by: John Li, MD (NUEM ‘24) Edited by: Amanda Randolph (NUEM ‘21) Expert Commentary by: John Bailitz, MD & Mike Macias, MD

SonoPro Tips and Tricks

Welcome to the NUEM Sono Pro Tips and Tricks Series where Sono Experts team up to take you scanning from good to great for a problem or procedure!

For those new to the probe, we recommend first reviewing the basics in the incredible FOAMed Introduction to Bedside Ultrasound Book and 5 Minute Sono. Once you’ve got the basics beat, then read on to learn how to start scanning like a Pro!

Point of care right upper quadrant ultrasound has been shown to be a highly sensitive (82-91%), specific (66-95%), cost effective and efficient modality for emergency medicine physicians to quickly and effectively identify biliary pathology [1-5]. But despite its widespread utility, right upper quadrant ultrasound can often be a technically difficult study for the beginner sonographer, as there are multiple factors that can influence its ease of acquisition ranging from patient body habitus to bowel gas shadowing, and sonographer experience has been shown to influence its efficacy [1, 6-7].

Beyond the classic patient with right upper quadrant pain, what other scenarios do Sono-Pros use right upper quadrant ultrasound?

Epigastric abdominal pain being “diagnosed” and even over treated as GERD. Pick up the probe in the symptomatic patient taking their PPI, EGD negative, or already treated for H. pylori

Unexplained right shoulder or back pain.

Colicky pain in the right flank but no urinary findings of nephrolithiasis.

My gallstones are back! But my gallbladder is gone. Look for choledocholithiasis.

Chronically ill elderly or immunosuppressed patients with unexplained fever or sepsis.

SonoPro Tips - How to scan like a Pro

Always Start Smart: To Fail to Prepare is to Prepare to Fail whether in ED POCUS or ED Thoracotomy.

Start with the patient in either the left lateral decubitus position or supine with the bed at approximately 30 degrees.

Let the patient know “I’ll be asking you throughout this brief exam to take medium to deep breaths and hold for 5 sec, then automatically breathe out.”

Still not not getting great views?

Scan between the ribs to use the liver as an acoustic window and avoid bowel gas. Switch to a small footprint phased array probe if needed.

Not sure which intercostal space to use? Try about 7 centimeters to the right of the patient’s xiphoid process!

Ask the patient to position their arms above their head to open the intercostal space.

Ask the patients to bend their knees to relax the abdominal muscles.

In young, thin patients, the gallbladder may be more anterior and superior-- if you are scanning subcostally, try flattening out the probe even more!

Even a Small Pain in the Neck can be a Big Problem!

Don’t forget the neck. There is a reason the gallbladder was so nicely distended and easy to find. Be sure to scan carefully in two orthogonal planes to pick up subtle stones in the neck of the gallbladder!

If there is a lot of nearby bowel gas, tell your tech to look for these stones if your surgeons require a confirmatory comprehensive radiology ultrasound before operating.

In this GIF, you can see a long-axis view of the gallbladder. When you are initially looking at the body and the fundus of the gallbladder, there are no clear shadowing stones. However, as the sonographer fans to the neck of the gallbladder, they can visualize multiple stones, which are casting shadows posteriorly. Image courtesy of the POCUS Atlas.

SonoPro Tips - Pro Pick Ups!

Is that a stone or is that something else in the gallbladder? Roll the patient and see if the “stone” moves!

If the stone in the fundus or body moves, then it’s more likely a mobile stone.

If it doesn’t move, then consider a polyp or a malignancy. Polyps or malignancies generally are non-shadowing while stones are shadowing!

Impacted, “non-mobile” Neck Stone = Big Problem and likely to progress to acute cholecystitis.

What’s causing that shadow?

Stones shadow posteriorly.

Edges shadow on the sides. Edge artifact results when ultrasound beams scatter passing by a smooth-walled structure, creating an anechoic stripe that could be confused with true shadowing!

What if the entire gallbladder is casting a shadow?

Think about a gallbladder FULL of stones! This will cause only the most anterior stones to show up on ultrasound.

Here, on the right side of the screen you see a cross section of the gallbladder that has a large stone in it-- this is casting a shadow so you do not see the posterior wall of the gallbladder at all. This is called the wall echo sign-- where you will only see the most anterior surface of the stone. Image courtesy of the POCUS Atlas.

4. What are some of those pesky mimics of acute cholecystitis?

Think about hepatic pathologies! Acute hepatitis can cause a clinical Murphy’s sign. You can also have patients who present similarly when they have a congestive hepatopathy from their CHF. Even cirrhotic patients can present with a tender RUQ!

Here, you can see a dilated gallbladder with a thickened anterior wall and a small amount of pericholecystic fluid, all of which are consistent with acute cholecystitis. Image courtesy of the POCUS Atlas.

In this still image, you can see a thickened gallbladder wall (although be sure to measure the anterior wall, as the posterior wall can be thickened due to posterior acoustic enhancement!) and a small amount of pericholecystic fluid. Image courtesy of the POCUS Atlas.

Here, you can see a dilated gallbladder with an obstructing stone in the neck of the gallbladder. Image courtesy of the POCUS Atlas.

SonoPro Tips - What the Pro’s Do Next!

Infographic courtesy of Justin Seltzer, MD

If you see nonshadowing masses in the gallbladder:

Measure it! If the polyp is >1cm, then there’s a ~50% chance that this could be malignant, so be sure to refer these patients for additional imaging and close follow up.

What if you’re hoping to be really thorough and get a beautiful image of the CBD, but despite your best efforts, you cannot find it?

Draw some LFTs! A number of our emergency medicine colleagues, including Becker et. al and Lahham et. al, have done studies on this and it has been shown to be very unlikely that the CBD will be pathologically dilated in the setting of normal LFTs. On the flip side, if the LFTs appear cholestatic in nature, that’s another indication for a right upper quadrant ultrasound! [9-10]

SonoPro Tips - Where to Learn More

Do you want to see more pathologic images that you may see when you are doing a right upper quadrant ultrasound? Be sure to check out The Pocus Atlas by our expert editor Dr. Macias! It’s a great resource that also shows some of the rarer etiologies of gallbladder pathology, such as emphysematous cholecystitis or choledocholithiasis.

If you’re interested in looking at some of the evidence behind the right upper quadrant ultrasound, be sure to check out the evidence atlas here as well!

Expert Commentary

Thank you to NWEM1 John Li for bringing this great idea for a NUEM Blog Series to life. And another thanks to NUEM Blog Founder Mike Macias for his help on both content and graphics!

This new series is intended to push your Sono skills from just good, to really great. We will not rehash the basics. There are already abundant great resources available that we are truly thankful for and utilize everyday. But instead, we will share SonoPro Tips to help you more quickly master challenging POCUS applications and procedures.

And there is no place better to start than Acute Cholecystitis. This is a great differentiator between the average and the expert clinician sonographer. As John outlines, start smart by expanding your indications and positioning your patient properly from the get go. Then breath, not you, the patient. Breath and hold again and again to bring the gallbladder and even difficult to discern pathology into clear view. Go beyond getting stones, and work to pick up, and explain other pathologies, as well as the bile ducts when needed.

Thanks again John and Mike! Looking forward to the next post in this new series...

John Bailitz, MD

Vice Chair for Academics, Department of Emergency Medicine

Professor of Emergency Medicine, Feinberg School of Medicine

Northwestern Memorial Hospital

Michael Macias, MD

Global Ultrasound Director, Emergent Medical Associates

Clinical Ultrasound Director, SoCal MEC Residency Programs

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Li, J. Randolph, A. (20201 Mar 22). SonoPro Tips and Tricks for Acute Cholecystitis. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Bailitz, J. Macias, M]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/sonopro-tips-and-tricks-for-acute-cholecystitis

Other Posts You May Enjoy

References

Jain A, Mehta N, Secko M, Schechter J, Papanagnou D, Pandya S, Sinert R. History, Physical Examination, Laboratory Testing, and Emergency Department Ultrasonography for the Diagnosis of Acute Cholecystitis. Acad Emerg Med. 2017 Mar;24(3):281-297. doi: 10.1111/acem.13132. PMID: 27862628.

Miller, Adam H., et al. “ED Ultrasound in Hepatobiliary Disease.” The Journal of Emergency Medicine, vol. 30, no. 1, 2006, pp. 69–74., doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2005.03.017.

Shekarchi B, Hejripour Rafsanjani SZ, Shekar Riz Fomani N, Chahardoli M. Emergency Department Bedside Ultrasonography for Diagnosis of Acute Cholecystitis; a Diagnostic Accuracy Study. Emerg (Tehran). 2018;6(1):e11. Epub 2018 Jan 20. PMID: 29503836; PMCID: PMC5827043.

American College of Emergency Physicians: Emergency Ultrasound Imaging Criteria Compendium. Oct. 2014, www.acep.org/globalassets/new-pdfs/policy-statements/emergency-ultrasound-imaging-criteria-compendium.pdf.

Hilsden R, Leeper R, Koichopolos J, et al. Point-of-care biliary ultrasound in the emergency department (BUSED): implications for surgical referral and emergency department wait times. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2018;3(1):e000164. Published 2018 Jul 30. doi:10.1136/tsaco-2018-000164

Ma, John, et al. Ma and Mateer's Emergency Ultrasound. McGraw-Hill Education, 2020.

Mallin, Mike, and Matthew Dawson. Introduction to Bedside Ultrasound: Volume 2. Emergency Ultrasound Solutions, 2013.

Macias, Michael. TPA, www.thepocusatlas.com/.

Becker BA, Chin E, Mervis E, Anderson CL, Oshita MH, Fox JC. Emergency biliary sonography: utility of common bile duct measurement in the diagnosis of cholecystitis and choledocholithiasis. J Emerg Med. 2014 Jan;46(1):54-60. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.03.024. Epub 2013 Oct 11. PMID: 24126067.

Lahham S, Becker BA, Gari A, Bunch S, Alvarado M, Anderson CL, Viquez E, Spann SC, Fox JC. Utility of common bile duct measurement in ED point of care ultrasound: A prospective study. Am J Emerg Med. 2018 Jun;36(6):962-966. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.10.064. Epub 2017 Nov 20. PMID: 29162442.

Imaging in PTAs

Written by: Cameron Jones, MD (NUEM ‘23) Edited by: Vidya Eswaran, MD (NUEM ‘20) Expert Commentary by: Josh Zimmerman, MD

The Use of Imaging for Diagnosis and Management of Peritonsillar Abscesses