Written by: Shawn Luo, MD (NUEM ‘22) Edited by: Steve Chukwuelebe, MD (NUEM '19) Expert Commentary by: Samia Farooqi, MD (NUEM '16)

Expert Commentary

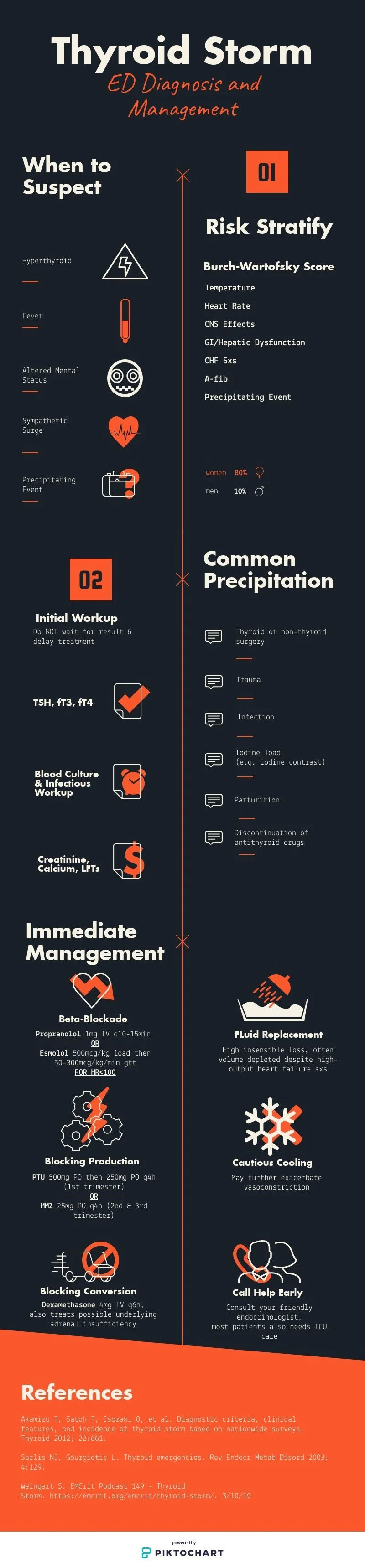

For those of you who have not yet cared for a patient in Thyroid Storm, I guarantee that the experience will humble you. As far as endocrine emergencies go, this one is (quite literally) a killer. In 1993, Burch and Wartofsky cited mortality rates as high as 20 to 50% [1]. In more recent literature, the mortality rate of this condition is still at a whopping 10% [2]. As you can see from the beautifully presented infographic above, there are a number of complexities that factor into the diagnosis and treatment of Thyroid Storm. This is in part due to the fact that thyroid hormone affects all organ systems, with clinical manifestations of disease involving everything from cardiac dysrhythmia to profound GI losses secondary to vomiting and diarrhea to acute psychosis. To ground this infographic in clinical reality, where we know that diagnoses are not always easy to make and the decision between one therapeutic option versus another is not always clear, I offer you just a few additional points:

1. Making this diagnosis requires that you actually think about it in the first place. There is no single diagnostic test or image that will clinch this diagnosis for you. The Burch and Wartofsky criteria are clinical findings that you as the provider must use in the correct context for them to be useful. This is a rare condition, and your availability bias will be working against you here. Patient presentations can be vague and there is incredible overlap with other disease processes, with chief complaints ranging from anxiety to vomiting and abdominal pain to leg swelling.

2. Once this diagnosis has been considered or made, understand that these patients have incredibly complex hemodynamics, with multiple potential factors in play at any given time: hypovolemia from profound GI losses, concomitant sepsis, high output cardiac failure, and cardiac systolic dysfunction. With regards to this last point, there is a high incidence of decompensated heart failure in patients with thyroid storm, and those with cardiogenic shock are at some of the greatest risk of mortality [2, 3, 4]. As such, it behooves you to re-assess these patients’ volume status frequently. Examine them closely, and then re-examine them. Use your bedside ultrasound to assess their cardiac output, IVC, and lung windows. While they may be profoundly hypertensive when you first administer a beta blocker, concomitant sepsis and hypovolemia may surface very quickly as the patient’s blood pressure plummets.

3. This leads to my next point: when given the choice between propranolol and esmolol in managing tachydysrhythmia (whether profound sinus tachycardia or atrial fibrillation) in the context of Thyroid Storm, strongly consider esmolol. The Japan Thyroid Association and Japan Endocrine Society Task Force specifically cites increased mortality rates in patients for whom propranolol was used versus esmolol or landiolol (super short-acting beta blocker used in Japan) [3]. Much of the benefit to using esmolol over propranolol is in its much shorter half-life. The alpha and beta half-life for propranolol are 10 minutes and 2.3 hours, respectively, whereas the alpha and beta half-life for esmolol are 2 minutes and 9 minutes, respectively. Once the infusion is stopped, the effect of esmolol will have completely disappeared by 18 minutes [3].

4. When asked during oral boards how you would manage a patient with Thyroid Storm, a response involving antithyroid agents, inorganic iodide, corticosteroids, and beta blockers would score you full marks. However, I would encourage you to also consider thoughtful administration of IV fluids (with frequent re-assessment of volume status), early empiric antibiotics, inotropic agents for patients in cardiogenic shock, and psychotropic medications as needed for restlessness/delirium/psychosis (with olanzapine preferred over haldol) [3].

Diagnosis and management of Thyroid storm in the Emergency Department requires us to draw upon so many of our expert skills in approaching undifferentiated and critically ill patients. I hope that these points help to provide you with just a few more tools to include in your arsenal as you go forth.

References

[1] Burch, HB, Wartofsky, L. (1993). Life-threatening thyrotoxicosis: Thyroid storm. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America, 22(2): 263-77.

[2] Akamizu, T. (2018). Thyroid Storm: A Japanese Perspective. Thyroid, 28:1.

[3] Satoh, T, et al. (2016). 2016 Guidelines for the Management of Thyroid Storm from The Japan Thyroid Association and Japan Endocrine Society (First edition). Endocrine Journal, 63: 12 (1025-1064).

[4] Bourcier, S, et al. (2020). Thyroid Storm in the ICU: A Retrospective Multicenter Study. Critical Care Medicine, 48:1 (83-90).

Samia Farooqi, MD

Assistant Professor

Department of Emergency Medicine

UT Southwestern

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Luo, S. Chukwuelebe, S. (2021, April 19). Thyroid Storm ED Diagnosis and Management. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Farooqi, S]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/thyroid-storm.