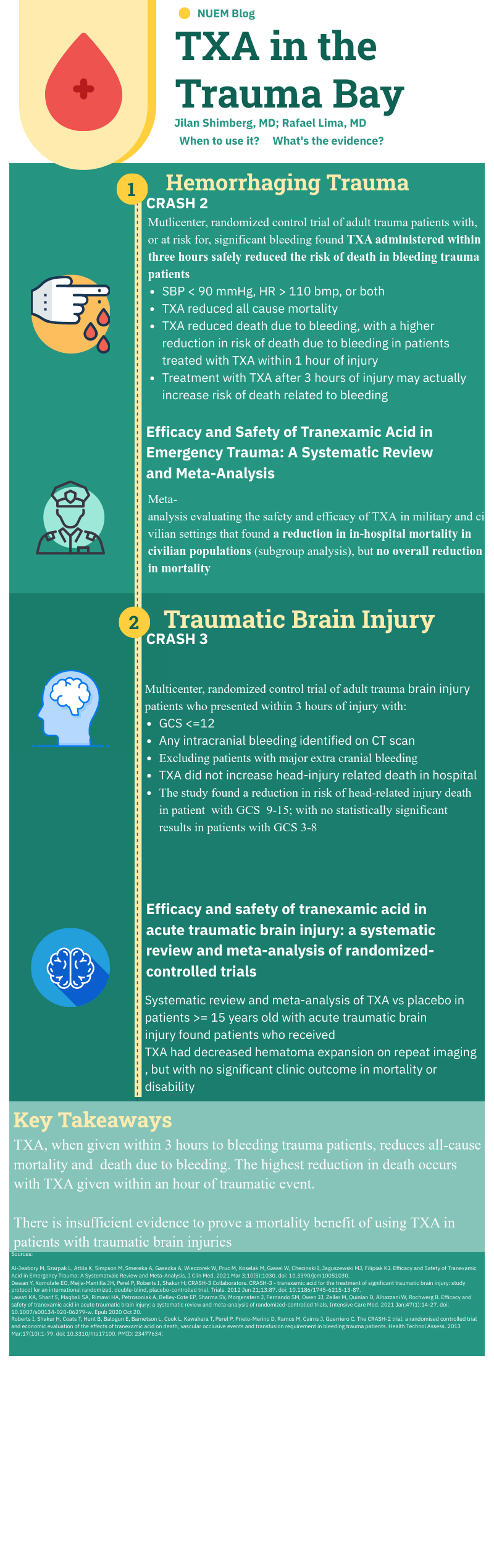

Written by: Jilan Shimberg, MD (NUEM ‘26) Edited by: Rafael Lima, MD (NUEM ‘23)

Expert Commentary by: Matthew R Levine, MD

Expert Commentary

Unlike many of the treatments and interventions we use in the Emergency Department and the trauma bay, tranexamic acid (TXA) has rather robust studies to guide usage. Like many interventions, however, even when there are studies with large numbers of patients and positive results, there are still barriers towards implementation. TXA is no different.

Working at a Level 1 Trauma Center and frequently interacting closely with the trauma surgeons through the Trauma Quality Management Committee, I often follow their lead when it comes to promising trauma innovations through the years such as TXA, REBOA, permissive hypotension, and so on. What I have observed is that our trauma surgeons tend to believe that there is benefit to properly timed TXA in the right trauma patients and that we do not use it enough. Yet use of TXA in trauma at our hospital has not been protocoled.

Why not? Some possibilities:

Someone usually (but not always) thinks to give it to patients who would benefit despite there not being a protocol (thanks ED pharmacists!).

The patients who need it most also need something else even more – source control of hemorrhage. Anything that slows or distracts from that may be counterproductive. It may not seem like a simple TXA infusion would delay anything. But keep in mind the multiple lines sick trauma patients may need and the often already chaotic nature of “the bay” getting the sickest patients the tubes, meds, lines, products, studies, and, ultimately, proper disposition during their “golden hour”. The nurses have many tasks, to say the least. But maybe this is an argument for why use of TXA should just be protocolized.

I bounced this off of our trauma section head to make sure I was not misrepresenting their thoughts. As a result, we are looking into protocolling its use. Thanks NUEM Blog!

Matthew Levine, MD

Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine

Department of Emergency Medicine

Northwestern Memorial Hospital

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Shimberg, J. Lima, R. (2024, Mar 11). TXA in the Trauma Bay. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Levine, M]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/txa-trauma