Written by: David Kaltman, MD (NUEM PGY-3) Edited by: Charles Caffrey, MD (NUEM Alum ‘18) Expert commentary by: Josh Waitzman, MD

Case: A 25 year-old man with no significant past medical history presents to the ED with discolored urine. He states that he does not exercise regularly, but two days ago he went to a spinning class with several co-workers. He endorses increasingly severe bilateral lower extremity soreness over the past 24 hours that has not improved with ibuprofen. Overnight, he began to note discoloration of his urine, prompting his presentation. Vital signs are unremarkable. Physical exam is notable for diffuse and equivalent tenderness to palpation of his thighs; his lower extremities are neurovascularly intact distally.

Clinical Questions: What should be the disposition of this patient: home vs. medical floor vs. ICU? Is the initial CK useful in this risk stratification?

This patient has a classic case of exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis. Rhabdomyolysis is a clinical syndrome and is variously defined; most criteria use CK > 5x upper limit of normal as a cutoff. The most common etiologies in adults are:

Trauma, often crush injury or prolonged downtime

Prolonged exertion, particularly in hot weather and in those who are not well conditioned

Toxicologic, including alcohol, sympathomimetics, PCP, carbon monoxide, statins, envenomations

Viral infection

Patients often present with myalgias, weakness, and dark urine. In severe cases, nausea and mental status changes (secondary to uremia or other metabolic catastrophe) may be present. Muscle necrosis leads to the release of intracellular contents into the systemic circulation, making hyperkalemia and hypocalcemia the most immediately life-threatening problems.

Workup should include:

Serial physical exams for compartment syndrome

ECG, given the likelihood of electrolyte derangements

Labs: Chemistry panel (including Mg and Phos), CBC, urinalysis, total creatine kinase (CK) *note: urine myoglobin is specific but not sensitive; its half-life is only 1-3 hours

If very ill-appearing, consider adding DIC panel, LDH, and hepatic chemistries

Does the total initial CK level in the ED correlate with risk of acute renal failure? Not really. The risk of renal failure depends more on concurrent conditions such as sepsis, acidosis, hypovolemia, and comorbidities. However, multiple reviews have shown that the risk is higher when the total level approaches 15,000. One 2013 retrospective review of 2,000 patients did not find any significant correlation until CK levels exceeded 40,000. On the other end, one prospective study showed that no patients with CK levels <5,000 went on to develop renal failure.

Management

Initial management should include identifying and treating the underlying cause (detoxification, removing offending agent, cooling, etc.), and then treating to prevent renal failure and other long term complications. Prompt IV fluid resuscitation can generally begin with a bolus of 1-2L. Much like DKA, do not give more than this until the patient is able to urinate. Once urination is proven, titrate fluid resuscitation to achieve about 250mL/hr of UOP (3mL/kg/hr). Urinary alkalinization with a bicarbonate drip is a controversial treatment that may have a renal protective effect; no randomized controlled trials to date have demonstrated benefit. This may be a reasonable option in severe cases if the urine is very acidic (pH<6.5) and if your hospital has an ICU experienced with a urinary alkalinization protocol. Signs of renal failure should merit nephrology consultation and consideration of dialysis.

Disposition

Consider:

Discharge with close follow up for patients who are generally healthy, have normal creatinine, downtrending CK, and can reliably consume lots of fluids at home

Medical admission for patients with AKI, co-morbidities (pre-existing or trauma, heat injury)

ICU admission for impending renal failure (unable to void, highly elevated creatinine, severe metabolic acidosis), arrhythmia, DIC, concern for early compartment syndrome

Case Conclusion

The patient is able to urinate after receiving 2L of NS. His initial CK is 45,000 but serum creatinine and potassium are within normal limits. He is admitted to the general medicine service where he receives aggressive IV fluid resuscitation. Fortunately, he does not develop acute kidney injury and is later discharged in his usual state of health with only a newfound aversion to bicycles.

Expert Commentary

The above is a really nice presentation of a mild-to-moderately severe case of rhabdomyolysis. A few additional points of emphasis:

Although we like to think about rhabdo as a disease of excess Cross Fit, the history often includes a broad variety of causes.

I think the most common rhabdomyolysis history in a patient on whom nephrology is consulted is “found down after a fall.” Patients can spend hours or days with prolonged muscle compression and resulting muscle breakdown. Individuals who have this presentation tend to be older and more frail, and often have more medical comorbidities like CKD, DM and HTN that predispose them to acute kidney injury.

In addition to the nice list of causes that Dr. Kaltman provides, I’d add a few other rarer, but can’t miss conditions, including

- seizure and electrocution injuries (which break down muscle from prolonged activation)

- compartment syndrome (from burns or vascular occlusion, including ECMO cannulation)

- eating quail (called “coturnism”). I’ve never actually seen this, but please call nephrology if you do! It makes for great cocktail party chatter.

I agree with the statements re: CK levels for diagnosis of rhabdomyolysis. There is no CK level that perfectly excludes rhabdomyolysis, but it is hard to attribute an AKI to rhabdomyolysis without a CK in the tens of thousands. CK can be added onto a mint green tube in our laboratory, which makes it an easy test to add on after you see hyperkalemia or AKI.

A very useful and rapid screening test for rhabdomyolysis is the urinalysis, which will often show large blood but few or no RBCs on microscopy. Both myoglobin and hemoglobin contain heme, which is recognized by the urine dipstick as “blood”; however free myoglobin (from rhabdomyolysis) or free hemoglobin (from hemolysis) do not appear in the urine as RBCs. The test can be done in under 30 minutes and allow for rapid diagnosis and initiation of therapy. Urine myoglobin can also be checked, but has a longer turnaround time.

Prompt treatment of the patient with aggressive (1-2L per hour to start) IV crystalloid resuscitation is critical to the management of rhabdomyolysis. I can’t overstate enough how important volume is. If a patient is failing medical management, it is often from under-resuscitation. I don’t necessarily buy into the “proving they can make urine” before giving more volume—keep giving volume and trial high dose diuresis or dialysis if the patient is showing clinical signs of volume overload.

In terms of which fluid to use, classically the recommendation has been for saline because balanced crystalloids contain potassium. However, the amount of potassium in LR is quite low, and LR has never been shown to cause hyperkalemia in patients.

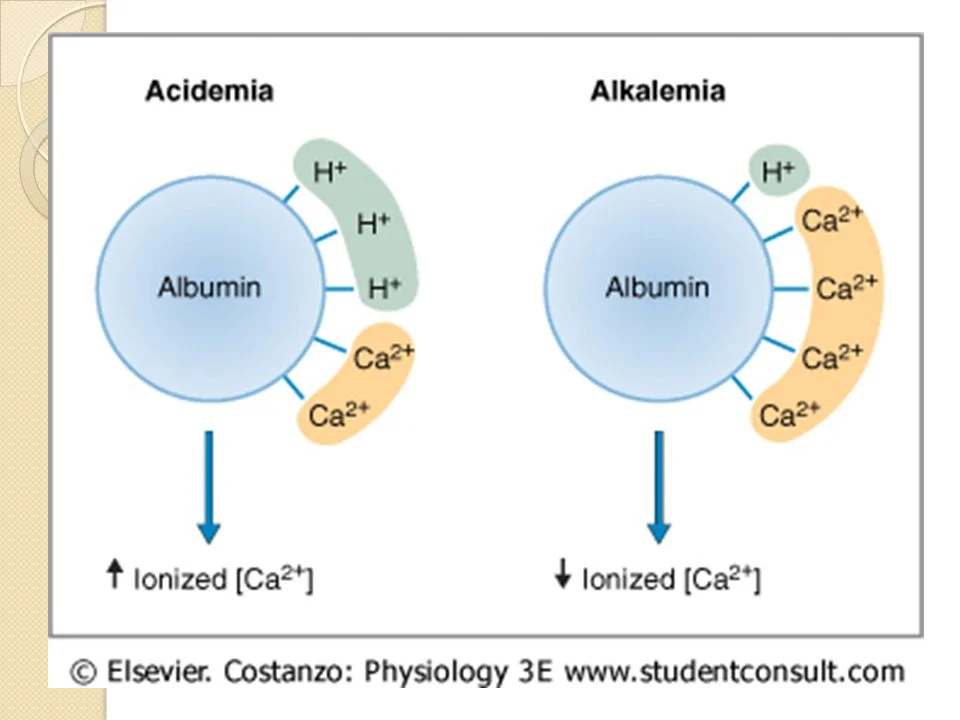

If patients are acidemic and have a normal/high calcium, isotonic bicarbonate is probably the crystalloid of choice. However, if the patient is hypocalcemic prior to receiving bicarbonate, treating their acidosis with bicarbonate can in further calcium binding to albumin, lower serum ionized calcium and symptomatic hypocalcemia.

TL;DR

Don’t forget about rhabdomyolysis in older people who are found down.

In true rhabdomyolysis CK should be 10,000+ to explain a severe kidney injury.

The UA is a fast test that can suggest rhabdomyolysis with large blood and few RBCs.

Be aggressive with early isotonic fluid resuscitation. We can always take fluid off later with dialysis if we need to.

LR or NS are reasonable fluid choices. Isotonic bicarbonate is great as long as the patient is both acidemic and does not have a low calcium.

Call nephrology if you are worried about your patient or if they say that they ate quail.

Josh Waitzman, MD

Nephrology Fellow

Northwestern Medicine

How to Cite This Post

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Kaltman D, Caffrey C (2019, February 18). Diagnose on Sight: Rhabdomyolysis [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Waitzman J]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/rhabdomyolysis

Other Posts You May Enjoy

References

Bosch, X., et al. (2009). "Rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney injury." N Engl J Med 361(1): 62-72.

Brown, C. V., et al. (2004). "Preventing renal failure in patients with rhabdomyolysis: do bicarbonate and mannitol make a difference?" J Trauma 56(6): 1191-1196.

Chatzizisis, Y. S., et al. (2008). "The syndrome of rhabdomyolysis: complications and treatment." Eur J Intern Med 19(8): 568-574.

Chavez, L. O., et al. (2016). "Beyond muscle destruction: a systematic review of rhabdomyolysis for clinical practice." Crit Care 20(1): 135.

McMahon, G. M., et al. (2013). "A risk prediction score for kidney failure or mortality in rhabdomyolysis." JAMA Intern Med 173(19): 1821-1828.

Parekh, R. (2014). Chapter 127: Rhabdomyolysis. Rosen's Emergency Medicine. R. H. John Marx, Ron Walls, Saunders: 1667-1675.