Expert Commentary

Thank you for the excellent and concise review. It’s been interesting to see procedural sedation practices change over the course of my training and career, as newer safe and easy options (propofol and ketamine) gained rapid popularity but have been challenged by drug shortages and well-publicized celebrity tragedies. Here is my typical practice, which is certainly not the only correct way but my strong preference:

A few factors on when to think about procedural sedation:

-Any painful procedure, particularly for potential for longer duration. This includes incision and drainage (especially Bartholin’s) and disimpaction. I’ve gotten some odd looks for suggesting it but it works out better for everyone involved.

-Consultant’s procedures, particularly big traumatic injuries which look nasty and like they need to be fixed. It’s easy to forget how terrible it is for the patient.

When I think about avoiding:

-medically complex patients

-difficult airways

-procedures that can wait

-procedures with low likelihood of success even under the best circumstances. If they need to go to the OR no matter what, that might be the best place to start.

My one exception are situations that are currently painful and need to be fixed now and can be fixed quickly, e.g. dislocated ankles. The likelihood of success with 100mcg of fentanyl within seconds to resolve a huge amount of pain now is exceedingly favorable.

The worst situation is trying to avoid procedural sedation with “just some morphine and maybe a little lorazepam” which quickly devolves into “a little more morphine” and “hmm maybe another dose of lorazepam.” Now it’s a procedural sedation that is both ineffective and unsafe.

My general process:

First I print out a checklist I made with the following preparation steps (details below):

RSI box (succinylcholine)

VL

airway cart (LMA, PEEP valve, DL gear)

nasal ETCO2 (plus ETT adapter)

4mg ondansetron now

bottle ketamine

bottle propofol

room ready (including suction, bag, anything required for the procedure)

Department ready?

Am I ready?

Procedure plan

Post-procedure planning (sling, splint)

The general principle is to set up at least as much as if I were performing RSI. A lot of this may seem like over-preparation, but the more I prepare, the luckier I get. Here is some more detail on each item:

RSI box (succinylcholine)

2 main purposes for the RSI box. First, if things go south, I will be intubating the patient, and need the medications to do so (i.e. NMBA). Second, if I am using ketamine, there is a small but nontrivial chance of laryngospasm, and of jaw thrust and bagging do not fix it, the patient needs NMBA. This is not a time to debate roc vs sux, so I always have sux in the room (even if roc isn’t slower when dosed appropriately at ≥1.2mg/kg, I don’t want to have to argue about it at the RCA). The easiest way for me to get these medications in the room is grabbing our RSI box, but this will depend on your department; simply grabbing a vial of sux with 1.5mg/kg is sufficient.

VL

If things go south, this is not the time for the intern to practice their DL. I always have the hyperangulated VL ready to go at the head of the bed, with a combo Mac VL/DL blade and a traditional Mac DL as backup, with stylets loaded with tubes ready to go.

Airway cart

We have nicely built airway carts with everything I need for bagging, difficult bagging, and difficult intubation. Primarily, what I want is gear for bagging, i.e. LMA and PEEP valve. All the usual backup is here as well (oral/nasal airways, bougie, cric gear).

Nasal ETCO2 (and ETT adapter)

The literature on end tidal in procedural sedation is interesting but I think generally answers a different question than the one I care about. I don’t look for qualitative changes in waveforms or quantitative changes in ETCO2 to predict hypoventilation; rather, it is the quickest and easiest way to see if the patient is breathing. No staring at their chest hoping to see chest rise. Simply look at the monitor: either there is a waveform and they are breathing, or there is not and they are not. It’s like a sedative for me, similar to supervising an intern using VL instead of DL: it makes the procedure much less stressful for me.

Additionally, by using ETCO2, it is now safe to provide supplemental oxygen via nasal cannula or reservoir facemask so if things go south, there is a much wider safety margin (i.e. the patient is preoxygenated for intubation).

4mg ondansetron now

As discussed above, it might help, it may not, and it’s safe and easy.

bottle Ketamine

bottle Propofol

I’ll discuss my medication strategies below, but the bottom line is I like to have multiple 100s of mg of each medication ready for each patient, because when I need to redose, it can be needed in a very short time.

Room ready

Other equipment I make sure is ready: suction, bag for mask ventilation. Other items like do I need vaseline gauze for splinting over an abrasion?

Is the Department ready?

Was an 80 year old with abdominal pain just roomed? Should I lay eyes on them and make a quick decision about an obvious CT? Is there a hospitalist hanging around who I can tell about another patient to send upstairs before I get stuck in a sedation for 45 minutes? Should I discharge anyone?

Am I ready?

Do I need to go to the bathroom? Has it been hours before I’ve had any calories?

Procedure plan

I always make sure to have a clear plan for the procedure—not just the sedation—well before we start. Who is doing what? What technique are we using? What are backup plans? Of course these questions apply to the sedation as well.

If a non-EM physicians is performing the procedure (e.g. ortho, or gen surg pulling a tunneled line) I try to make sure that they understand my definition of “ready” is not the same as in the OR, and I make sure they are ready to start the actual procedure as soon as the meds are working. This is not a judgment in any way; rather, the ER simply isn’t the OR.

Post-procedure planning

Few things are more frustrating than getting a difficult shoulder reduced only to have it slip out while someone is hunting down the sling I forget to get beforehand, that I knew I would need (see also: ordering post-intubation meds with RSI meds in an intubation). Obviously if something needs to be splinted we need the gear and whoever is doing the splint. And, if there are abrasions going under the splint, petroleum gauze, etc.

Medication choices

I typically choose between ketamine and propofol on a spectrum.

Factors on the propofol side: young, healthy, BP/respiratory reserve, shorter procedure, ortho procedure (propofol is much better at loosening up patients, plus these often end quickly).

Factors on the ketamine side: older, more comorbidities, less respiratory reserve, longer procedures, non-reduction procedures, more protractedly-painful procedures (e.g. I&D).

Obviously these are not absolutes and I tend to plan on using ketofol quite a bit. I usually have enough cognitive space and hands available to dose them separately (generally 0.5mg/kg ketamine first, then 0.5mg/kg propofol as needed) but in more constricted settings I will mix 1:1 if I don’t have the bandwidth.

I will say I have been tending to more and more ketamine-only sedations. Usually I start with the intention of using ketamine-first ketofol, particularly if the patient needs to be loosened up for a reduction, but I am continually surprised by how little I end up needing the propofol.

As noted above, for solo propofol, I pretreat with fentanyl as propofol is not inherently analgesic.

I appreciate the debate about midazolam for pretreatment for ketamine, but the rates of substantial post-sedation agitation are low enough that I simply treat that when it happens, as not all but most ketamine respiratory depression only happens with co-administered sedatives.

Other than lack of availability of other options, there is no reason to use fentanyl/midaz anymore.

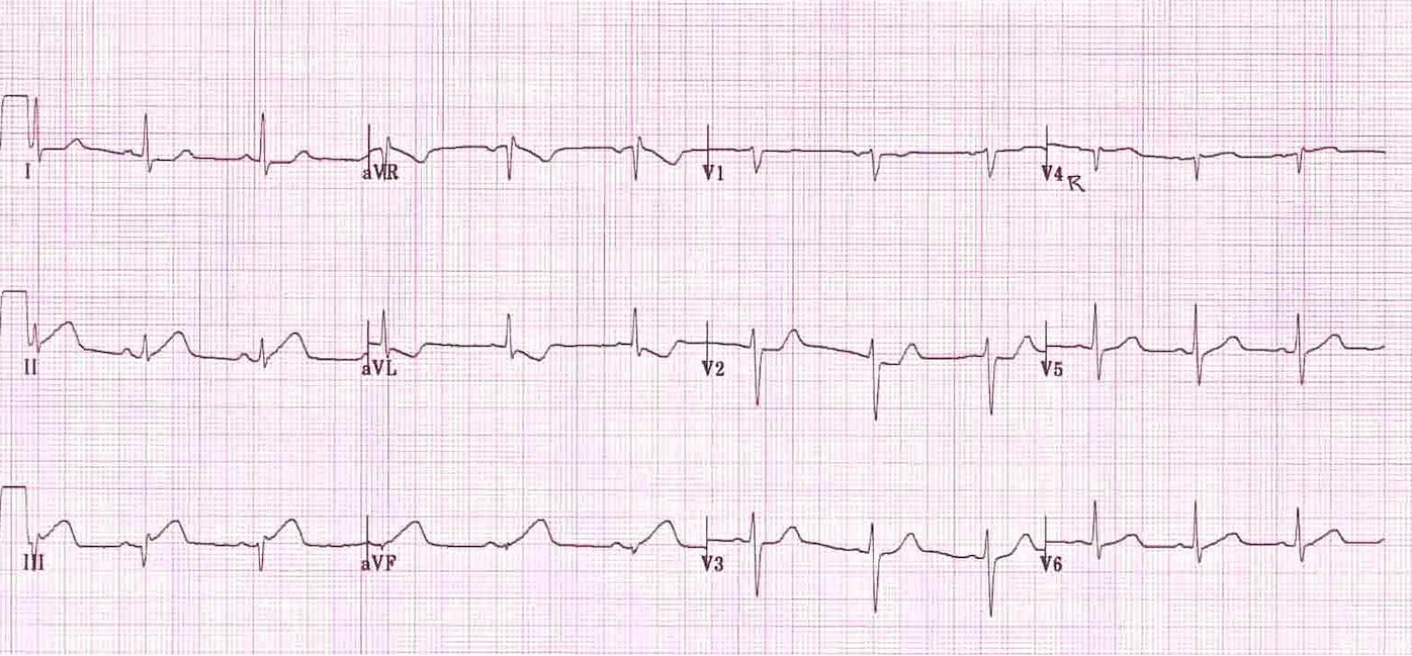

Lastly, I’ve stopped using etomidate. The rate of myoclonus is simply too high. Myoclonus easily defeats the reduction, and even for cardioversion, it makes checking the rhythm, getting an ECG, monitoring the sat, etc. very difficult. Ultimately, it’s just a headache we don’t need, particularly as we have so many other safe and effective agents.

As I said above, these are more my style preferences than the only absolutely correct choices, and I am always happy to at least discuss adapt to the circumstances including others’ preferences (or trying something different so the residents can gain experience with different techniques).

![Figure 1: Sonographic view of trachea showing air-mucosa interface with posterior reverberation and shadowing artifact. [Photo courtesy of John Bailitz, MD]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/549b0d5fe4b031a76584e558/1572626234251-VL5QSV3R6S608OO7J8OI/1.+Figure+1+-+Trachea.png)

![Figure 2: Clip demonstrating the bullet sign: a single air-mucosa interface with increased posterior shadowing and artifact indicates the trachea has been intubated. [Photo courtesy of John Bailitz, MD]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/549b0d5fe4b031a76584e558/1572626261525-86AN0IKGCSGN5EHY11VN/image-asset.gif)

![Figure 3: Clip demonstrating the double tract sign: the appearance of a second air-mucosa interface with posterior artifact adjacent to the trachea indicates the esophagus has been intubated. [Photo courtesy of John Bailitz, MD]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/549b0d5fe4b031a76584e558/1572626372841-E4OFNNGZHEOI7ECDRIJP/3.+Figure+3+-+Double+Tract+Sign.gif)

![Figure 1: Bruising patterns that suggest child abuse. [6]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/549b0d5fe4b031a76584e558/1570459114532-IVTA7KT3PX1J6DGC3U3L/Figure+1%3A+Patterns+of+Bruising)

![Figure 2: Forced immersion burn of buttocks with bilateral, symmetric leg involvement in a “stocking” pattern. [7]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/549b0d5fe4b031a76584e558/1570459322548-EFHGSFQ962QP9FU5DNJN/Figure+2%3A+Burn+patterns+that+suggest+non-accidental+trauma)

![Figure 3: Classic metaphyseal lesion. White arrows denote femoral metaphyseal separation and black arrow denotes a proximal tibial lesion or “bucket handle.” [1]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/549b0d5fe4b031a76584e558/1570459580501-8461RMF0P9706GJW7XJU/Figure+3%3A+Fractures+of+NAT)

![Figure 4: Posterior and lateral rib fractures of differing ages indicative of NAT [4]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/549b0d5fe4b031a76584e558/1570460464292-4QFTGMDQAB64NQBSYD9N/Figure+4%3A++Rib+fractures+of+differing+ages+indicative+of+NAT)

![Figure 5: Fundus of child with AHT with too-numerous-to-count retinal hemorrhages indicated by the black arrows. [8] The white arrow indicates small pre-retinal hemorrhages. The white arrowhead denotes hemorrhage extending into the peripheral retina…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/549b0d5fe4b031a76584e558/1570460641270-3V7M52RMMV1QDMZ3PA1S/Figure+5%3A+Occular+manifestations)

![Figure 6: Elements of the Skeletal Survey. Although a full skeletal survey is currently the standard of care for patients with NAT, there are ongoing research efforts to tailor X-ray imaging more specifically to each patient. [1]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/549b0d5fe4b031a76584e558/1570461092995-EBKSMB5DI0GTGXY0R75N/Figure+6%3A+Skeletal+surgery)

![Image from: Scott Weingart. Podcast 060 – On Human Bondage and the Art of the Chemical Takedown. EMCrit Blog. Published on November 13, 2011. Accessed on March 8th 2019. Available at [https://emcrit.org/emcrit/human-bondage-chemical-takedown/ ].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/549b0d5fe4b031a76584e558/1567388477962-KRXLKHZYC5XNCEGD8VRQ/image-asset.jpeg)