Written by: Zach Schmitz, MD (PGY-3) Edited by: Andrew Berg, MD (NUEM ‘19) Expert Commentary by: Jake Stelter, MD

Marathon: The Collapsed Athlete

You’ve been enjoying a beautiful, 71 degree day wrapping ankles and rehydrating runners at the last marathon medical tent, just one mile from the finish. Suddenly, you get a different, more concerning type of call - there’s a runner down about a block south.

You fight against the flow of runners and finally see your patient on the left side of the course. He’s laying on his back and a bystander has placed an ice bag on his head. He tells you his name is Tony, but can’t tell you where he is or what he was doing. A friend says he was slowing down and looking unsteady before sitting on the curb. He’s sweating, working a little hard to breathe, and he has a 2+ radial pulse. What is your approach?

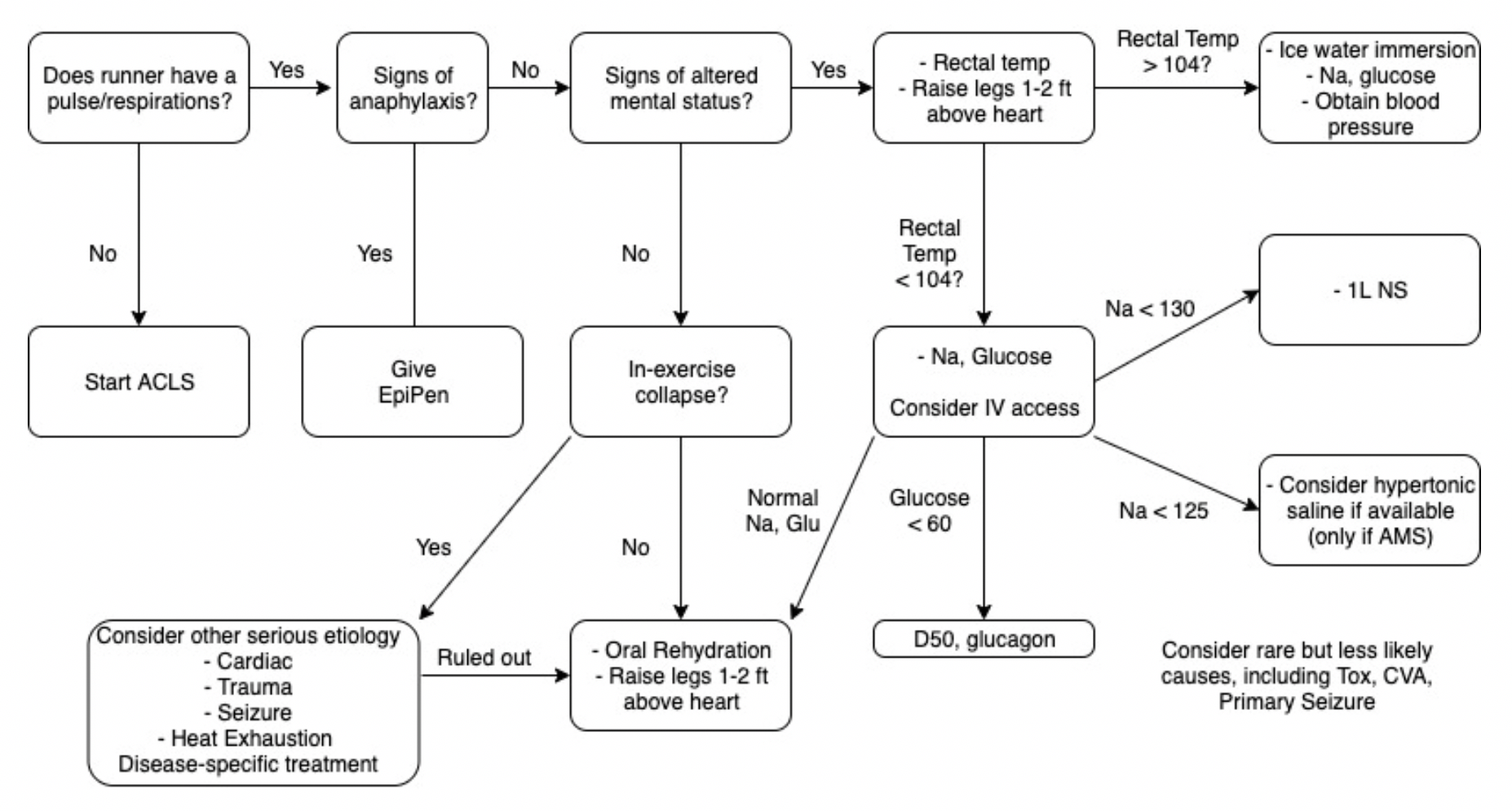

What to rule out first:

Just as with other ED patients, the first thing to do is rule out or intervene on life-threatening causes of runner’s collapse. Collapse during exercise is particularly concerning. There are five main causes of downed runners in that category: Sudden Cardiac Arrest, Exertional Heat Stroke, Anaphylaxis, Hypoglycemia, and Hyponatremia [1]. Below is an approach aimed toward addressing these concerns.

1. Sudden Cardiac Arrest

Suggested by an absent pulse and/or abnormal respirations.

Do not delay treatment. Start ACLS/BLS as your training and equipment allows and transport to a nearby ED.

Extremely rare[2]

2. Anaphylaxis

Suggested by any combination wheezes/stridor, shortness of breath, swelling, skin changes, nausea/vomiting, and altered mental status.

Treatment will likely be limited to IM epinephrine, as antihistamines, H2 blockers, and steroids are not routinely stocked in medical tents.

3. Exertional Heat Stroke

Suggested by altered mental status and a rectal temperature of > 104 degrees F.

These patients should be placed in an ice bucket immediately – any delay will risk permanent neurologic dysfunction.

Ice bucket immersion has been shown to reduce core body temperature 3x faster than ice towels and 15x faster than ice packs over major arteries[3].

Rapid on-site cooling is associated with better outcomes than immediate transfer to an emergency department for cooling. Those on site cooling end-points are controversial, but getting below 102 degrees F consistently leads to a safe transfer.[4]

You have to use rectal temperatures, as other temperature measurements have proven unreliable in a marathon setting.[4}

4. Hypoglycemia

Suggested by a spectrum from tremor, anxiety, diaphoresis, and altered mental status, up to seizure and coma.

Patients should be treated with glucose and transferred to a nearby medical facility.

5. Hyponatremia

Suggested by paresthesias, nausea/vomiting, and altered mental status, up to seizure and coma.

In one study of the Boston Marathon, 13% of runners had sodium values < 130, and 0.6% had critical values < 120. Those with longer race times, weight gain during the race, and those at the extreme ends of the BMI scale were more likely to have problems.[5]

Normal saline should be started for patients with initial Na of 130 or below, and 3% NS may be considered if Na < 125.

Thankfully, the above conditions comprise the minority of visits to medical tents at the marathon (including for downed runners). So what do you do with someone who is down and lightheaded but with a temperature of 99.3, sodium of 138, glucose of 98, and no signs of anaphylaxis? Collapse during exercise is still concerning, even after ruling out the causes above. You’ll want to confirm the patient can tolerate oral rehydration, place in a Trendelenberg position, and likely refer for further testing.

Collapse after exercise is more common, and, fortunately, often benign. Exercise associated collapse is likely to be the most frequent condition you encounter if you are in the final medical tent.

Exercise Associated Collapse (EAC)

Although considered to be more a chief complaint than diagnosis, EAC is defined as “a collapse in conscious athletes who are unable to stand or walk unaided as a result of light headedness, faintness and dizziness or syncope causing a collapse that occurs after completion of an exertional event.”[4] In one study, it accounted for 59% of patient presentations at the final medical tent.[1]

While running, increased oxygen demand by muscle leads to increased cardiac output and decreased peripheral vascular resistance. Skeletal muscle works as “second heart” for the race, overcoming this decrease in PVR to increase venous return. This mechanism is lost when running stops, and blood pools in the lower extremities. Cardiac output cannot be maintained, and perfusion is decreased. Further, the baroreceptor reflex controlling this mechanism is often compromised during long exercise. [6]

It is a fairly simple mechanism to reverse, and therefore a simple condition to treat. Placing the patient in a Trendelenberg position with the legs above the heart will usually achieve a fluid equilibrium in 10-30. Holtzhausen showed that these patients have no different electrolyte concentrations and are no more volume depleted than runners who finished the race without complication, so IV fluids are unnecessary[7]. However, keep in mind these people just ran a marathon, so they could probably use a little oral rehydration.

These patients should prove capable of sitting, then standing, then walking and eating before being discharged from the tent. If they show signs of altered mental status, vital sign abnormalities, or electrolyte imbalances, they should be treated appropriate and then transferred to an emergency department.

The vast majority of runners visiting a marathon medical tent are fully capable of finishing the race and just need help working out a cramp, covering up a blister, or grabbing some gel to cool a sore muscle. However, serious conditions do happen, and it is important to keep them in mind the next time you volunteer at your local marathon.

Take away points:

Life-threatening pathology is certainly possible in this relatively healthy cohort

Sudden cardiac arrest, exertional heat stroke, anaphylaxis, hypoglycemia, and hyponatremia should be considered for every down runner with altered mental status

Approach to the down runner: make sure you don’t need ACLS on scene > transfer to tent for rectal temp > Na, Glucose

If rectal temp is > 104, go directly to ice bath. Fully cool before transferring patient from tent

Although syncope post race can be scary, EAC is likely to resolve with 10-30 minutes of raised legs and oral rehydration

Expert Commentary

This is a great review of managing marathon runners who are acutely ill. It is important to keep in mind the diagnoses pointed out when dealing with a collapsed athlete.

1. Sudden Cardiac Arrest: This should be treated promptly following BLS/ACLS protocols. In this situation, the goal is to get to early defibrillation if possible as the most common cause is going to be a shockable arrhythmia, either ventricular fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia. The resources immediately available to you will vary depending on where on the course the patient goes down. Early activation of EMS is critical as they will bring with them both the means of transportation as well as ACLS supplies to aid in resuscitation.

2. Altered Mental Status: In a marathon athlete, the most important and life-threatening cause of altered mental status that needs to be ruled out is exertional heat stroke. As correctly pointed out, a core rectal temperature should be obtained on any athlete that is altered. Once identified as having a core temp over 103F, the athlete should be immediately cooled in an ice water tub until their temperature is 102F. At this point, the athlete should be removed from the water. Cooling below 102F can cause rebound hypothermia as cool peripheral blood shunts to the core. Avoid starting IV’s in runners prior to cooling, as getting blood into the tubs will contaminate them. If the athlete is normothermic and altered, check for hypoglycemia and treat accordingly.

3. Hyponatremia: Exercise-Induced Hyponatremia (EIN) is a relatively rare but very serious complication of endurance events. It is generally caused by excess sodium loss (sweating) that is often accompanied by excess free water intake. In a patient that is having signs and symptoms of neurologic dysfunction that is normothermic and not hypoglycemic, consider EIN. Common signs and symptoms include paresthesias, confusion, muscle weakness, cramping and seizures. If you have the ability to check a rapid sodium, then you can treat accordingly. If the patient’s sodium level is below 130 WITHOUT neurological symptoms, restrict free water intake and consider oral rehydration with electrolyte solutions. Sparingly administer isotonic IV fluids, no more than 250-500mL at a time and recheck the sodium level after each small bolus. If a patient falls into the category of hypervolemic hyponatremia, they may actually have an excess of ADH hormone and giving fluid may precipitate an even further drop in sodium. If a hyponatremic patient is having any neurological manifestation, especially seizures, the treatment is administration of 3% sodium chloride solution in 50-100mL boluses.

Also, as pointed out, be sure to consider other potential causes of your patient’s symptoms, including but not limited to cardiac pathology, trauma, stroke, and exercise associated collapse. Patients that are undifferentiated will often need to be transported to the nearest Emergency Department, as you are unlikely to have the resources to complete a diagnostic work-up in your course medical tent.

Jacob Stelter, MD

Instructor of Clinical Emergency Medicine

Primary Care Sports Medicine Fellow

University of Cincinnati

Medical Committee - Lead ICU Tent Coordinator

Bank of America Chicago Marathon

How to Cite This Post

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Schmitz Z, Berg, A. (2020, April 20). Marathon: The Collapsed Athlete. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Stelter, J]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/marathon

Other Posts You Might Enjoy:

References

[1] Roberts W, O’connor F, Grayzel J. Preparation and management of mass participation endurance sporting events. UpToDate. May 23 2017. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/preparation-and-management-of-mass-participation-endurance-sporting-events

[2] Roberts W.O., and Maron B.J.: Evidence for decreasing occurrence of sudden cardiac death associated with the marathon. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005; 46: pp. 1373-1374

[3] Casa D et al. Exertional Heat Stroke: New Concepts Regarding Cause and Care. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2012 May-Jun;11(3):115-23.

[4] Childress MA, O'Connor FG, Levine BD. Exertional collapse in the runner: evaluation and management in fieldside and office-based settings. Clin Sports Med. 2010 Jul;29(3):459-76. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2010.03.007.

[5] Almond et al. Hyponatremia among runners in the Boston Marathon. N Engl J Med. 2005 Apr 14;352(15):1550-6.

[6] Asplund CA, O'Connor FG, Noakes TD Exercise-associated collapse: an evidence-based review and primer for clinicians Br J Sports Med 2011;45:1157-1162.

[7] Holtzhausen LM1, Noakes TD, Kroning B, de Klerk M, Roberts M, Emsley R. Clinical and biochemical characteristics of collapsed ultra-marathon runners. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1994 Sep;26(9):1095-101.

[8] Madan S., Chung E., The Syncopal Athlete. American College of Cardiology. http://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2016/04/29/19/06/the-syncopal-athlete. Apr 29 2016. Accessed 10 1 2017.