Written by: Megan Chenworth, MD (NUEM ‘24) Edited by: Abiye Ibiebele, MD (NUEM ‘21) Expert Commentary by: John Bailitz, MD & Shawn Luo, MD (NUEM ‘22)

SonoPro Tips and Tricks

Welcome to the NUEM Sono Pro Tips and Tricks Series where Sono Experts team up to take you scanning from good to great for a problem or procedure! For those new to the probe, we recommend first reviewing the basics in the incredible FOAMed Introduction to Bedside Ultrasound Book and 5 Minute Sono. Once you’ve got the basics beat, then read on to learn how to start scanning like a Pro!

Did you know that focused transthoracic cardiac ultrasound (FOCUS) can help identify PE in tachycardic or hypotensive patients? (It has been shown to have a sensitivity of 92% for PE in patients with an HR>100 or SBP<90, and approaches 100% sensitivity in patients with an HR>110 [1]). Have a hemodynamically stable patient with PE and wondering how to risk stratify? FOCUS can identify right heart strain better than biomarkers or CT [2].

Who to FOCUS on?

Patients presenting with chest pain or dyspnea without a clear explanation, or with a clinical concern for PE. The classic scenario is a patient with pleuritic chest pain with VTE risk factors such as recent travel or surgery, systemic hormones, unilateral leg swelling, personal or family history of blood clots, or known hypercoagulable state (cancer, pregnancy, rheumatologic conditions).

Patients presenting with unexplained tachycardia or dyspnea with VTE risk factors

Unstable patients with undifferentiated shock

When PE is suspected but CT is not feasible: such as when the patient is too hemodynamically unstable to be moved to the scanner, too morbidly obese to fit on the scanner, or in resource-limited settings where scanners aren’t available

One may argue AKI would be another example of when CT is not feasible (though there is some debate over the risk of true contrast nephropathy - that is a discussion for another blog post!)

How to scan like a Pro

Key is to have the patient as supine as possible - this may be difficult in truly dyspneic patients

If difficulty obtaining views arise, the left lateral decubitus position helps bring the heart closer to the chest wall

FOCUS on these findings

You only need one to indicate the presence of right heart strain (RHS).

Right ventricular dilation

Septal flattening: Highly specific for PE (93%) in patients with tachycardia (HR>100) or hypotension (SBP<90) [1]

Tricuspid valve regurgitation

McConnell’s sign

Definition: Akinesis of mid free wall and hypercontractility of apical wall (example below)

The most specific component of FOCUS: 99% specific for patients with HR>100bpm or SBP<90 [1]

Tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE)

The most sensitive single component of FOCUS: TASPE < 2cm is 88% sensitive for PE in tachycardic and hypotensive patients; 93% sensitive when HR > 110 [1]

Where to FOCUS

Apical 4 Chamber (A4C) view: your best shot at seeing it all

Find the A4C view in the 5th intercostal space in the midclavicular line

Optimize your image by sliding up or down rib spaces, sliding more lateral towards the anterior axillary line until you see the apex with the classic 4 chambers - if the TV and MV are out of the plane, rotate the probe until you can see both openings in the same image; if the apex is not in the middle of the screen, slide the probe until the apex is in the middle of the screen. If you are having difficulty with this view, position the patient in the left lateral decubitus.

Important findings:

RV dilation: the normal RV: LV ratio in diastole is 0.6:1. If the RV > LV, it is abnormal. (see in the image below)

Septal flattening/bowing is best seen in this view

McConnell’s sign: akinesis of the free wall with preserved apical contractility

McConnell’s Sign showing akinesis of the free wall with preserved apical contractility

4. Tricuspid regurgitation can be seen with color flow doppler when positioned over the tricuspid valve

Tricuspid regurgitation seen with color doppler flow

5. TAPSE

Only quantitative measurement in FOCUS, making it the least user-dependent measurement of right heart strain [3]

A quantitative measure of how well the RV is squeezing. RV squeeze normally causes the tricuspid annulus to move towards the apex.

Fan to bring the RV as close to the center of the screen as possible

Using M-mode, position the cursor over the lateral tricuspid annulus (as below)

Activate M-mode, obtaining an image as below

Measure from peak to trough of the tracing of the lateral tricuspid annulus

Normal >2cm

How to measure TAPSE using ultrasound

Parasternal long axis (PSLA) view - a good second option if you can’t get A4C

Find the PSLA view in the 4th intercostal space along the sternal border

Optimize your image by sliding up, down, or move laterally through a rib space, by rocking your probe towards or away from the sternum, and by rotating your probe to get all aspects of the anatomy in the plane. The aortic valve and mitral valve should be in plane with each other.

Important findings:

RV dilation: the RV should be roughly the same size as the aorta and LA in this view with a 1:1:1 ratio. If RV>Ao/LA, this indicates RHS.

Septal flattening/bowing of the septum into the LV (though more likely seen in PSSA or A4C views)

Right heart strain demonstrated by right ventricle dilation

Parasternal Short Axis (PSSA) view: the second half of PSLA

Starting in the PSLA view, rotate your probe clockwise by 90 degrees to get PSSA

Optimize your image by fanning through the heart to find the papillary muscles - both papillary muscles should be in-plane - if they are not, rotate your probe to bring them both into view at the same time

Important findings:

Septal flattening/bowing: in PSSA, it is called the “D-sign”.

“D-sign” seen on parasternal short axis view. The LV looks like a “D” in this view, particularly in diastole.

Subxiphoid view: can add extra info to the FOCUS

Start just below the xiphoid process, pointing the probe up and towards the patient’s left shoulder

Optimize your image by sliding towards the patient’s right, using the liver as an echogenic window; rotate your probe so both MV and TV are in view in the same image

Important findings

Can see plethoric IVC if you fan down to IVC from RA (not part of FOCUS; it is sensitive but not specific to PE)

Plethoric IVC that is sensitive to PE

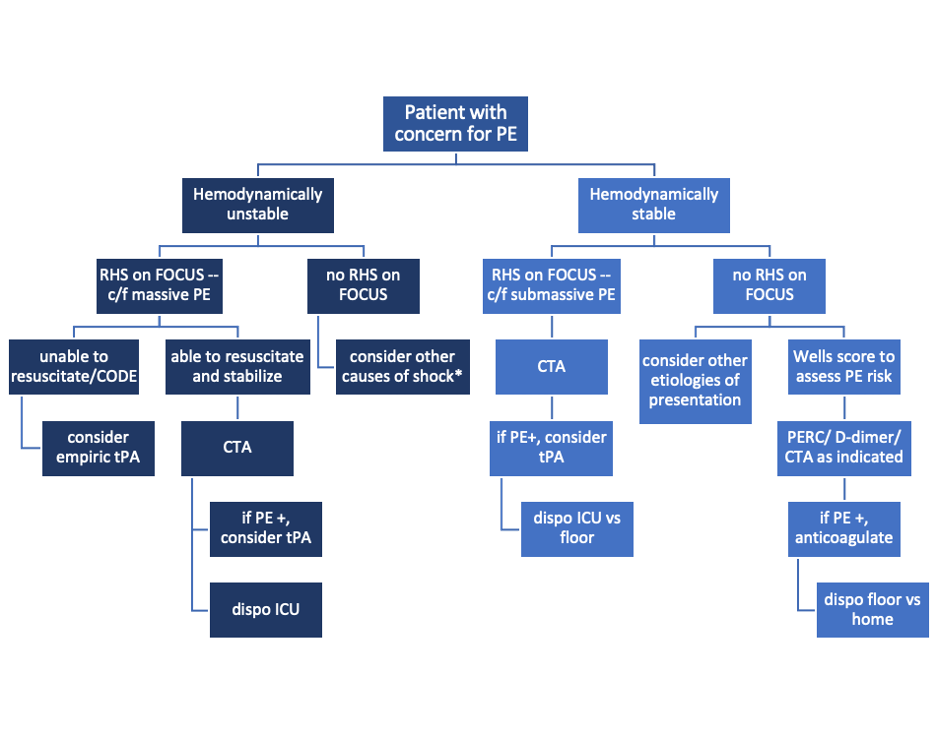

What to do next?

Sample algorithm for using FOCUS to assess patients with possible PE.

*cannot completely rule out PE, but negative FOCUS makes PE less likely

Limitations to keep in mind:

FOCUS is great at finding heart strain, but the lack of right heart strain does not rule out a pulmonary embolism

Systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that the overall sensitivity of FOCUS for PE is 53% (95% CI 45-61%) for all-comers [5]

Total FOCUS exam requires adequate PSLA, PSSA, and A4C views – be careful when interpreting inadequate scans

Can see similar findings in chronic RHS (pHTN, RHF)

Global thickening of RV (>5mm) can help distinguish chronic from acute RHS

McConell’’s sign is also highly specific for acute RHS, whereas chronic RV failure typically appears globally akinetic/hypokinetic

SonoPro Tips - Where to Learn More

Right Heart Strain at 5-Minute Sono: http://5minsono.com/rhs/

Ultrasound GEL for Sono Evidence: https://www.ultrasoundgel.org/posts/EJHu_SYvE4oBT4igNHGBrg, https://www.ultrasoundgel.org/posts/OOWIk1H2dePzf_behpaf-Q

The Pocus Atlas for real examples: https://www.thepocusatlas.com/echocardiography-2

The Evidence Atlas for Sono Evidence: https://www.thepocusatlas.com/ea-echo

References

Daley JI, Dwyer KH, Grunwald Z, Shaw DL, Stone MB, Schick A, Vrablik M, Kennedy Hall M, Hall J, Liteplo AS, Haney RM, Hun N, Liu R, Moore CL. Increased Sensitivity of Focused Cardiac Ultrasound for Pulmonary Embolism in Emergency Department Patients With Abnormal Vital Signs. Acad Emerg Med. 2019 Nov;26(11):1211-1220. doi: 10.1111/acem.13774. Epub 2019 Sep 27. PMID: 31562679.

Weekes AJ, Thacker G, Troha D, Johnson AK, Chanler-Berat J, Norton HJ, Runyon M. Diagnostic Accuracy of Right Ventricular Dysfunction Markers in Normotensive Emergency Department Patients With Acute Pulmonary Embolism. Ann Emerg Med. 2016 Sep;68(3):277-91. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.01.027. Epub 2016 Mar 11. PMID: 26973178.

Kopecna D, Briongos S, Castillo H, Moreno C, Recio M, Navas P, Lobo JL, Alonso-Gomez A, Obieta-Fresnedo I, Fernández-Golfin C, Zamorano JL, Jiménez D; PROTECT investigators. Interobserver reliability of echocardiography for prognostication of normotensive patients with pulmonary embolism. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2014 Aug 4;12:29. doi: 10.1186/1476-7120-12-29. PMID: 25092465; PMCID: PMC4126908.

Hugues T, Gibelin PP. Assessment of right ventricular function using echocardiographic speckle tracking of the tricuspid annular motion: comparison with cardiac magnetic resonance. Echocardiography. 2012 Mar;29(3):375; author reply 376. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2011.01625_1.x. PMID: 22432648.

Fields JM, Davis J, Girson L, et al. Transthoracic echocardiography for diagnosing pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2017;30:714–23.e4.

Expert Commentary

RV function is a frequently overlooked area on POCUS. Excellent post by Megan looking specifically at RV to identify hemodynamically significant PEs. We typically center our image around the LV, so pay particular attention to adjust your views so the RV is optimized. This may mean moving the footprint more laterally and angle more to the patient’s right on the A4C view. RV: LV ratio is often the first thing you will notice. When looking for a D-ring sign, make sure your PSSA is actually in the true short axis, as a diagonal cross-section may give you a false D-ring sign. TAPSE is a great surrogate for RV systolic function as RV contracts longitudinally. Many patients with pulmonary HTN or advanced chronic lung disease can have chronic RV failure, lack of global RV thickening. Lastly remember, that a positive McConnell’s sign is a great way to distinguish acute RHS from chronic RV failure.

John Bailitz, MD

Vice Chair for Academics, Department of Emergency Medicine

Professor of Emergency Medicine, Feinberg School of Medicine

Northwestern Memorial Hospital

Shawn Luo, MD

PGY4 Resident Physician

Northwestern University Emergency Medicine

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Chenworth, M. Ibiebele, A. (2021 Oct 4). SonoPro Tips and Tricks for Pulmonary Embolism. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Bailitz, J. Shawn, L.]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/sonopro-tips-and-tricks-for-pulmonary-embolism