Written by: Jason Chodakowski, MD (NUEM PGY-3) Edited by: Evan Davis, MD (NUEM Alum ‘18) Expert commentary by: Benjamin Schnapp, MD (NUEM Alum ‘16)

Background

Serotonin syndrome is a condition characterized by increased serotonergic activity in the central nervous system. This can result from therapeutic use, inadvertent interactions, or intentional self-poisoning of any combination of drugs that have the net effect of increasing serotonergic neurotransmission. Serotonin syndrome most often causes mental status changes, autonomic and neuromuscular hyperactivity while severe cases may result in DIC, rhabdomyolysis, metabolic acidosis, renal failure, ARDS, and death.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the most commonly implicated group of medications, with other culprits including serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), and recreational drugs like cocaine, ecstacy, and amphetamines. The syndrome classically occurs after the initiation of a single drug, after increasing the dose of an existing medication, or simultaneous administration of two serotonergic agents. Serotonin syndrome involving a monoamine oxidase inhibitor may be especially severe and more likely to result in death. It’s important to keep in mind that antidepressants aren’t the only serotonergic agents, and that many commonly administered medications such as tramadol, meperidine, fentanyl, dextromethorphan, and linezolid among others have serotonergic activity.

Clinical Features

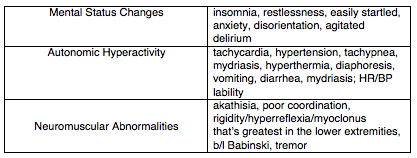

The majority of cases present within 24 hours, and most within 6 hours of a change or initiation of drug. The syndrome is characterized by the triad of mental status changes, autonomic hyperactivity, and neuromuscular abnormalities. The diagnosis, however, can be quite challenging as these three non-specific domains of symptomatology can present with very wide spectrum of severity.

Diagnosis

There is no confirmatory test for serotonin syndrome, the diagnosis is entirely clinical. The best validated diagnostic criteria for serotonin syndrome is the Hunter Toxicity Criteria. To fulfill the Hunter Criteria, a patient must have taken a serotonergic agent and meet one of the following conditions:

Spontaneous clonus

Inducible clonus plus agitation or diaphoresis

Ocular clonus plus agitation or diaphoresis

Tremor plus hyperreflexia

Hypertonia plus temperature above 38ºC plus ocular clonus or inducible clonus

Differential Diagnosis:

Multiple other entities can present with a general sympathomimetic picture and should be considered in the differential diagnosis. These include:

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS)

Anticholinergic toxicity

Malignant hyperthermia

Intoxication from other sympathomimetic agents

Opioid withdrawal

Sepsis

Meningitis/encephalitis

Heat stroke

Delirium tremens

Thyroid storm

Neuromuscular findings, particularly myoclonus is an important distinguishing feature of serotonin syndrome from the above etiologies.

Serotonin syndrome can typically be differentiated from other similar conditions by its characteristic neuromuscular findings of hyperreflexia and clonus. For example, conditions such as NMS, malignant hyperthermia, and sympathomimetic toxicity all typically lack these features.

Labs/Imaging

While serotonin syndrome is a clinical diagnosis labs and imaging can be useful for monitoring complications in severe cases and to help differentiate from other diagnoses in the differential above. The most severe complications of serotonin syndrome include DIC, rhabdomyolysis, metabolic acidosis, renal failure, and ARDS. Thus, you should consider checking the following to evaluate for these:

CBC

BMP

CK

LFTs

Lactic acid

DIC panel

UA

CXR

If the diagnosis is uncertain, you might also consider blood cultures, CT brain, lumbar puncture, urine toxicology screen and/or TSH to evaluate for other things on the differential.

Management

The mainstay of therapy for serotonin syndrome is supportive care. The main hallmarks of management include:

Discontinue the offending agent.

IV fluids to correct hypovolemia

Sedation with benzodiazepines. Options include Lorazepam 2-4mg and Diazepam 5-10mg, which can be repeated every 10 minutes.

Aggressive control of hyperthermia with standard cooling techniques. Since hyperthermia is often due to increased muscle activity in serotonin syndrome, consider early intubation and paralysis in severe hyperthermia.

Management of autonomic instability. Consider esmolol and nitroprusside for hypertension and tachycardia, while avoiding long-acting agent like propranolol. MAOIs can sometimes cause hypotension, treat this with pressors such as phenylephrine, epinephrine, and norepinephrine as necessary.

If benzodiazepines and supportive care fail to improve agitation and correct vital signs, you can consider cyproheptadine, an antidote of sorts with anti-histaminergic and anti-serotonergic activity. Cyproheptadine is only dosed orally, with a recommended initial dose of 12mg, followed by 2 mg every two hours until clinical response is seen. Symptoms from serotonin syndrome typically resolve within 24 hours.

Expert Commentary

Gathering an accurate medication history is the key to making this diagnosis. As mentioned above, this is a clinical entity that generally manifests quite quickly after medication initiation. Checking the medication list in the computer isn’t going to help you here - ask the patient what kinds of new medication they might have been prescribed or they might be taking. Remember - selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are not the only class of medications that can affect serotonin and it may be the interacting agent that you’re looking for. Besides the above, other common medications that can be problematic include triptans, ondansetron, valproic acid, carbamazepine, lithium, cyclobenzaprine, and even herbal supplements like St. John’s wort (patients may not think supplements are worth mentioning!).

One underappreciated aspect of serotonin syndrome is the extent to which it occurs on a spectrum. Studying for the boards and looking at the Hunter Criteria can leave one with the impression that clonus is necessary to make the diagnosis of serotonin syndrome. This is not the case, and it has been suggested that many milder cases, presenting with only symptoms such as tachycardia, diarrhea, and restlessness, may be going missed. Again, medication history is essential here.

Benjamin Schnapp, MD

Assistant Residency Program Director, University of Wisconsin-Madison Emergency Medicine

How To Cite This Post

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Chodakowski J, Davis E (2018, November 19). Serotonin Syndrome [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Schnapp B]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/serotonin-syndrome

Other Posts You May Enjoy

References

Boyer, Edward W., and Michael Shannon. "The serotonin syndrome." New England Journal of Medicine 352.11 (2005): 1112-1120.

LoVecchio, Frank, and Erik Mattison.. "Atypical and Serotonergic Antidepressants." Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 8e Eds. Judith E. Tintinalli, et al. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2016,

Mason, Peter J., Victor A. Morris, and Thomas J. Balcezak. "Serotonin Syndrome Presentation of 2 Cases and Review of the Literature." Medicine 79.4 (2000): 201-209.