Written by: Evelyn Huang, MD (NUEM ‘24) Edited by: Julian Richardson (NUEM ‘21)

Expert Commentary by: Tyler Black, MD, FRCPC

COVID-19 has been difficult for everyone. Deaths, isolation, loss of work, and countless other hardships abound. With this, comes the concern for mental health crises. In a survey from June 2020, 11% of adults reported thoughts of suicide in the past 30 days [1]. It can be hypothesized that the pandemic has increased suicide rates. However, does this bear out in the literature? As frontline workers, and oftentimes the only interaction that patients have with the healthcare system, it is particularly important that we identify the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of the patients that we see every day.

In Japan, researcher used a cross-sectional study to analyze national suicide rates during the COVID-19 pandemic. They found that suicide rates in 2020 were increased in October and November for men and in July through November for women when compared to 2016-2019. Increases in suicide rates were more pronounced with men and women that are younger than 30 [2]. This supports the idea that suicide rates increased as a result of the pandemic, especially with the younger population.

However, the trends in the United States are different. A study conducted in the US looked at suicide rates in Massachusetts from March to May 2020. Excluding data from pending death investigations, they found that the incident rate for suicide death was 0.67 per 100,000 person-months for the pandemic period as compared to 0.80 in the corresponding period in 2019. The researchers point to a sense of shared purpose, connections via video platforms, anticipated government aid, and mental health awareness campaigns as possible explanations for the stable rate of suicide deaths [3]. Another study looked at United States suicide related searches during the beginning of the pandemic. Researchers found that internet searches for suicide decreased during the early stages of the COVID pandemic (March to July 2020). While this may be surprising, there is literature that shows that catastrophic events can be associated with increased social support and reduce suicidal outcomes [4]. However, as the pandemic lengthens, more research is needed to see the trends in the data.

The next question is whether the same trend of decreased suicidality also applies to the pediatric population. A pediatric emergency department in Texas looked at the resulted of their routine suicide risk screenings for patients aged 11-21. They found a significantly higher rate of suicidal ideation in March and July 2020 and a higher rate of suicide attempts in February, March, April, and July 2020 when compared to the same months in 2019 [5]. It has also been cited that prior to the pandemic, suicide was the 10th leading cause of death in the United States, but the 2nd leading cause of death among people aged 12-17 [1]. This makes our interactions with the pediatric population even more important and argues for suicide risk screening for every patient.

Looking historically, there are differing trends for different global catastrophes. One researcher found that World War I did not influence United States suicide rates, whereas the great Influenza Epidemic increased suicide rates [6]. Another study looked at suicide rates in Hong Kong during the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 2003. They found an increase in older adult suicide in April 2003 when compared to 2002. These researchers cited loneliness and disconnectedness in the older community as a possible explanation [7]. While there are many different factors that go into increased suicidality, trends seen in the past can help guide policy and actions today.

Research is still needed to look at the current trends of suicide rates. The question is whether suicide rates will change as the pandemic continues to lengthen and the sense of shared purpose wanes and social isolation continues. The mental health of our patients is likely to be impacted long after the pandemic ends.

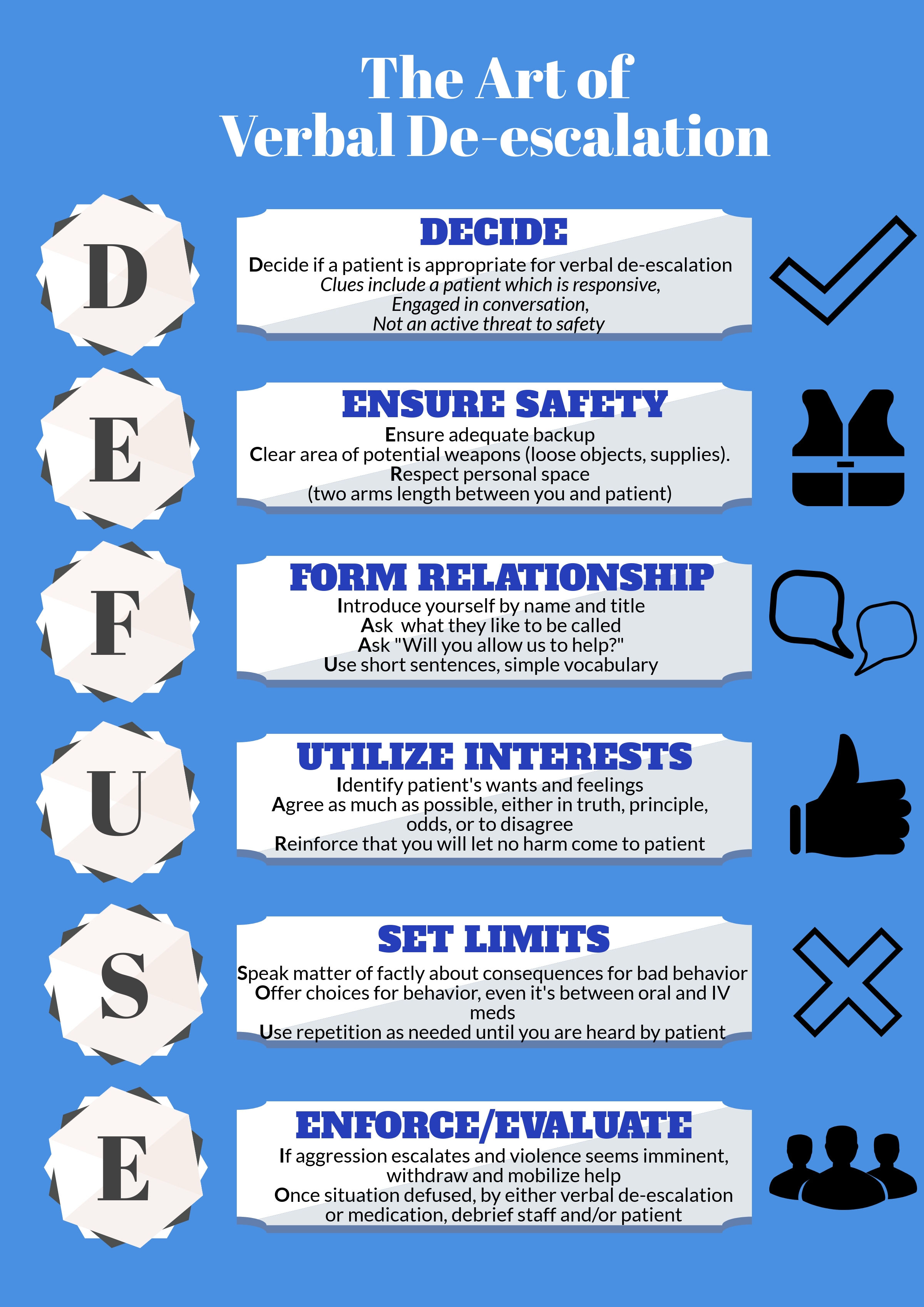

A study conducted in California found that emergency department patients presenting with deliberate self-harm or suicidal ideation had an increased risk of suicide or other mortality during the first year after their initial presentation in the emergency department [8]. This is a troubling trend, but also presents an opportunity for improvement. As emergency physicians, it is also important that we keep vigilant and take the time to talk about mental health. A common fear is that asking about suicide will prompt suicidal ideation, but research has shown that this is not the case [9]. There are several suicide screening tools that can be used in the ED, such as the Suicide Assessment 5‐step Evaluation and Triage (SAFE‐T) and American College of Emergency Physicians ICAR2E [9]. What is important is to ask, because patients will often reveal things to us that they do not mention to their loved ones. Build suicide screenings into your general practice, watch out for risk factors, and support those that are seek help.

References

1. Panchal, Nirmita, et al. The Implications of COVID-19 for Mental Health and Substance Use. Kaiser Family Foundation, 10 Feb. 2021, www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/the-implications-of-covid-19-for-mental-health-and-substance-use/.

2. Sakamoto H, Ishikane M, Ghaznavi C, Ueda P. Assessment of Suicide in Japan During the COVID-19 Pandemic vs Previous Years. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e2037378. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.37378

3. Faust JS, Shah SB, Du C, Li S, Lin Z, Krumholz HM. Suicide Deaths During the COVID-19 Stay-at-Home Advisory in Massachusetts, March to May 2020. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2034273. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.34273

4. Ayers JW, Poliak A, Johnson DC, et al. Suicide-Related Internet Searches During the Early Stages of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2034261. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.34261

5. Hill RM, Rufino K, Kurian S, Saxena J, Saxena K, Williams L. Suicide ideation and attempts in a pediatric emergency department before and during COVID-19. Pediatrics. 2020; doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-029280

6. Wasserman IM. The impact of epidemic, war, prohibition and media on suicide: United States, 1910-1920. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1992 Summer;22(2):240-54. PMID: 1626335.

7. Cheung YT, Chau PH, Yip PS. A revisit on older adults suicides and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) epidemic in Hong Kong. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008 Dec;23(12):1231-8. doi: 10.1002/gps.2056. PMID: 18500689.

8. Goldman-Mellor S, Olfson M, Lidon-Moyano C, Schoenbaum M. Association of Suicide and Other Mortality With Emergency Department Presentation. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(12):e1917571. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.17571

9. Brenner, J. M., Marco, C. A., Kluesner, N. H., Schears, R. M., & Martin, D. R. (2020). Assessing psychiatric safety in suicidal emergency department patients. Journal of the American College of Emergency Physicians Open, 1(1), 30-37.

Expert Commentary

This review is a comprehensive summary of the challenges and nuances of suicide epidemiology. Though it goes against the narrative many hold, in the United States we have preliminary but reliable data for suicides two years into the pandemic, we have not seen an increase in suicide rate in any age group (Figure 1) [1,2]. This reassuring news is tempered by the knowledge that prior to the pandemic, a decade-long trend of increasing suicide rates has maintained, and children, adults, and older adults are much more likely to die of suicide now in America than they were in 2010 [3].

Figure 1. Odds ratio for suicide, by age groups (A = under 18 years; B = 18 to 64 years; C = above 64 years). Years are grouped to match with the onset of the pandemic (March 2020), such that each data point represents April of that year to the following March (instead of the typical January to December presentation). The comparator for each year’s odds of suicide is a sum of the odds between April 2017 and March 2020. The shaded vertical lines represent the 95% confidence interval for odds ratio, and they are hidden behind the markers for the adult group due to the small confidence interval.

Whenever considering suicide risk, it is crucial to remember that there are not direct links between suicidal thinking, suicide attempts or visits to the emergency department, and deaths by suicide. Up to 60% of people die of suicide on their first attempt, and the vast majority (95%) of people who attempt suicide do not die of suicide, so while it is important to see the danger in suicidal presentations to emergency department, it is crucial to be aware of the challenges in predicting who will live and who will die by suicide and focus on a person-centered approach to understanding an individual’s risk and protective factors[4, 5].

I applaud the authors for encouraging all clinicians to consider suicide risk in all patients and to become comfortable with routine screening. This may never demonstrate a reduction in suicide rates in rigorous research, but we have ample evidence that having open, genuine discussions about psychological, social, and health problems regarding suicide risk is beneficial to the patients we care for [6].

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 1999-2020 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2021. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999-2020, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. Accessed at http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html on Dec 1, 2022.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Provisional Mortality on CDC WONDER Online Database. Data are from the final Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2020, and from provisional data for years 2021-2022, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. Accessed at http://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd-icd10-provisional.html on Dec 1, 2022

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, June 28). Suicide data and statistics. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved December 1, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/suicide-data-statistics.html

4. Bostwick, J. M., Pabbati, C., Geske, J. R., & McKean, A. J. (2016). Suicide attempt as a risk factor for completed suicide: Even more lethal than we knew. American Journal of Psychiatry, 173(11), 1094–1100.

5. Hawton, K., Lascelles, K., Pitman, A., Gilbert, S., & Silverman, M. (2022). Assessment of suicide risk in mental health practice: shifting from prediction to therapeutic assessment, formulation, and risk management. The Lancet Psychiatry.

6. Dazzi, T., Gribble, R., Wessely, S., & Fear, N. T. (2014). Does asking about suicide and related behaviours induce suicidal ideation? What is the evidence?. Psychological medicine, 44(16), 3361-3363.

Tyler Black, MD, FRCPC

Assistant Clinical Professor

Department of Psychiatry

The University of British Columbia

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Huang, E. Richardson, J. (2023, Jan 2). COVID-19 and Mental Health. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Black, T]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/covid-mental-health