Written by: Saabir Kaskar, MD (NUEM ‘23) Edited by: Nick Wleklinski (NUEM ‘22)

Expert Commentary by: Fan Caprio, MD

Neurology Scores: LVO, NIHSS, and ICH

As first line providers, being able to effectively communicate with ancillary services and specialties is key to advancing patient care within the emergency department. When patients present with symptoms concerning for ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, there are a variety of clinical decision tools available to help direct interventions and predict patient outcomes. Having a basic understanding of these scoring systems helps ED providers communicate more effectively with our neurology colleagues. This post highlights indications, strengths, and limitations of common stroke assessment scales used in the prehospital and hospital setting.

Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale (CPSS)

The Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale is a simple, easy to teach, three-part evaluation and is the most cited scale in statewide EMS protocols. Patients with one of these three findings, as a new event, will have 72% probability of ischemic stroke. If they have three of these deficits, that probability increases to 85%. Further, those scoring higher on this scale are more likely to have a large vessel occlusion (LVO) and warrant transfer to a comprehensive stroke center. One major limitation is that the CPSS does not identify features of posterior circulation strokes.

Figure 1: Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale components

Predicting Large Vessel Occlusion

There are many stroke severity scales that are useful in predicting large vessel occlusion (LVO) in the pre-hospital setting. Early LVO detection is useful as these patients have better outcomes if transported to comprehensive stroke centers (CSCs) which have endovascular interventions, such as thrombectomy, readily available. Such interventions are not available at primary stroke centers (PSC). LVO screening tools include the Rapid Arterial Occlusion Evaluation Scale (RACE), the Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Severity Scale (CP-SSS/C-STAT), the Los Angeles Motor Scale (LAMS), and the Emergent Large Vessel Occlusion Scale (ELVO). While these scales are good, none have achieved an optimal sensitivity/specificity combination which is why there is no “gold standard” test per the most recent 2019 AHA guidelines (Powers et al. Guidelines for Early Mgmt of Patients with AIS. Stroke 2019).

The Rapid Arterial Occlusion Evaluation Scale (RACE), for example, is one of these severity scales that predicts stroke caused by large vessel occlusion. It is based on the NIHSS but provides quicker assessment in the pre-hospital environment. It focuses on facial palsy, extremity motor function, head deviation, gaze deviation and aphasia or agnosia. The scale ranges from 0-9 with scores ≥ 5 being associated with detection of an LVO. RACE has a sensitivity of 85% and specificity of 68% for LVO at scores ≥ 5.

Another example of a LVO screening tool is the Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Severity Scale (CP-SSS/CSTAT) which is important to differentiate from the CPSS outlined above. CSTAT focuses on gaze deviation, level of consciousness and arm weakness. Both RACE and CSTAT are validated in the prehospital setting and with external data sets. However, CSTAT is more convenient with fewer items to score.

EMS protocol in Chicago (Region XI), utilizes a two-tier system that first involves the Cincinnati Stroke Scale and finger to nose test. If either aspect is abnormal, then stroke severity is assessed with the 3-Item Stroke Scale (3I-SS) which assesses level of consciousness, gaze preference and motor function, scored from 0-6. If the 3I-SS score is ≥4 and the last known normal is ≤6 hours ago then the patient is transported to the closest CSC instead of the closest primary stroke center (PSC), as long as the added transport time is not >15 minutes.

National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS)

The NIHSS is a 11-part scoring tool and is the gold standard when assessing stroke patients in hospital (figure 3). Higher scores indicate a more severe stroke and usually correlate with infarct size on CT and MRI. Taken within the first 48 hours of acute stroke, the NIHSS helps predict three month and one-year clinical outcomes. For example, patients with a NIHSS of 1-4 have a high likelihood of functional independence and favorable outcome regardless of treatment. The NIHSS does not serve as the primary clinical guide in determining tPA administration. However, given that higher scores correlate with larger infarct size, caution is advised when considering tPA in patients with a NIHSS >22 as there is a higher risk of hemorrhagic conversion (see figure 2 for full tPA exclusion criteria). Analysis from subjects of the NINDS trials show that a NIHSS of >20 was associated with a 17% rate of intracranial hemorrhage with tPA when compared to 3% hemorrhage rate in patients with a score of <10.

Figure 2: Contraindications for tPA administration

Overall, the NIHSS is a reliable scoring tool to quicky assess the effects of stroke. Medical providers and nurses have been shown to have similar levels of accuracy when trained. Limitations include assessing posterior circulation stroke that involve gait abnormality, dizziness, or diplopia.

Figure 3: NIHSS, adopted from the American Stroke Association

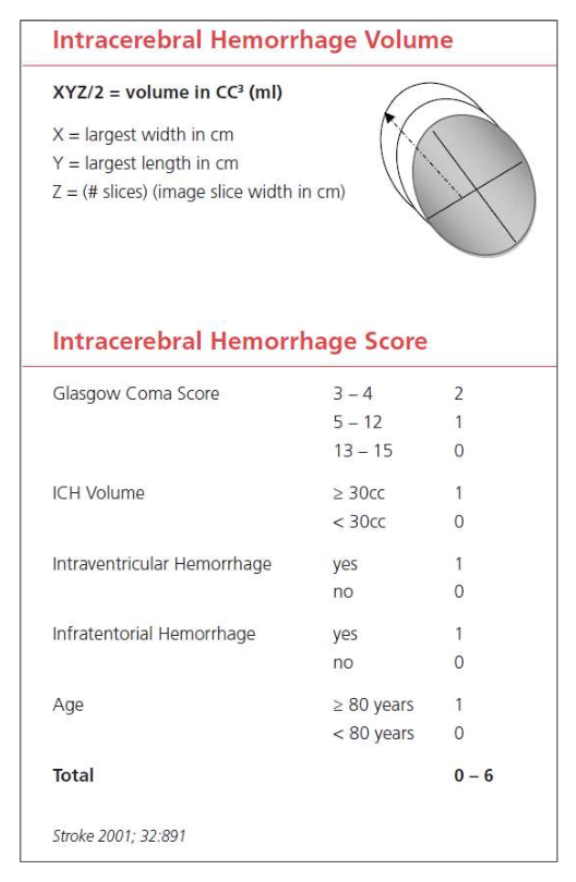

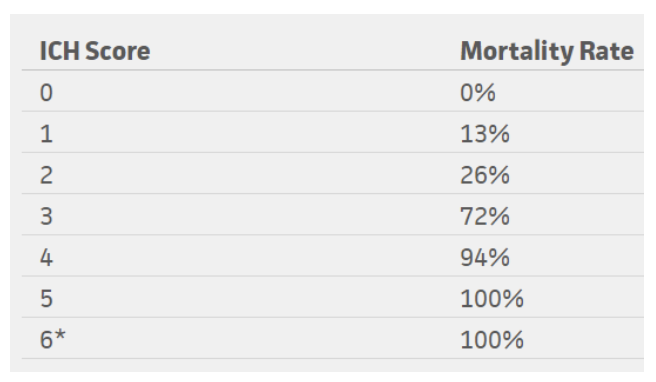

Intracerebral Hemorrhage Score (ICH Score)

The ICH score is an important tool when evaluating a hemorrhagic stroke. This score was developed to standardize clinical grading of ICH and to improve communication between providers. This five-component scoring system (Figure 4) helps quantify ICH severity and subsequently 30-day mortality (Figure 6) with a sensitivity of 66%. It is not used to determine treatment modality. This score helps universalize the grading of ICH severity, providing a standardized language that can be used between EM providers, neurologists, and neurosurgeons. Further, this score can help providers guide goals of care conversations with patient’s families and determine appropriate level of care or transfer.

Figure 4: ICH score, adapted from the American Stroke Association

Figure 5: Mortality rates based on ICH score

*No patients in the study scored 6, but estimated 100% mortality

Conclusion

In summary, it is important to understand how to utilize these scoring tools for ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. Knowing how to interpret pre-hospital stroke scores and how to calculate a NIHSS score accurately and quickly is helpful in not only quantifying severity but also in improving communication between providers. Improved understanding and effective use of these tools can help better advance care of our stroke patients efficiently. These tools can also remind us of the severity of the neurologic deficit we observe on clinical exam. Subsequently, this can be helpful in guiding discussions with patients and their families regarding the severity of their condition.

References

Adams HP Jr, Davis PH, Leira EC, et al. Baseline NIH Stroke Scale score strongly predicts outcome after stroke: A report of the Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST). Neurology 1999; 53:126.

Goldstein, L. (2019). Use and utility of stroke scales and grading systems. Up To Date

Goldstein L, Bertels C, Davis JN. Interrater reliability of the NIH stroke scale. Arch Neurol 1989; 46:660.

Generalized efficacy of t-PA for acute stroke. Subgroup analysis of the NINDS t-PA Stroke Trial. Stroke 1997; 28:2119.

Hemphill JC 3rd, Bonovich DC, Besmertis L, Manley GT, Johnston SC. The ICH score: a simple, reliable grading scale for intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2001 Apr;32(4):891-7. PubMed PMID: 11283388.

Kothari RU, Pancioli A, Liu T, et al. Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale: reproducibility and validity. Ann Emerg Med 1999; 33:373.

Pérez de la Ossa N, Carrera D, Gorchs M, et al. Design and validation of a prehospital stroke scale to predict large arterial occlusion: the rapid arterial occlusion evaluation scale. Stroke 2014; 45:87.

Schlemm L, Ebinger M, Nolte CH, Endres M. Impact of Prehospital Triage Scales to Detect Large Vessel Occlusion on Resource Utilization and Time to Treatment. Stroke 2018; 49:439.

Expert Commentary

Thanks for writing this comprehensive summary of common screening tools used in stroke patients. Having a good handle on these tools will allow you to quickly and effectively communicate with comanaging care providers. It is also important to understand how and why each scale was developed, so they can be used in the appropriate setting to expedite care in extremely time-sensitive neurologic emergencies.

Keep in mind that scales are merely screening tools and are not meant to give a definitive diagnosis. No scale is perfect, but you have highlighted some that yield the highest sensitivity and specificity for identifying a potential stroke patient. In addition to leaning on these scales as decision support tools, always use your clinical judgement. A few things to remember in addition to the neurologic symptoms:

* Strokes are potentially intervenable within the first 24 hours:

1. Up to 4.5 hours – IV-TPA / tenecteplase.

2. Up to 6 hours – Thrombectomy with LVO on vessel imaging.

3. Up to 24 hours – Thrombectomy with LVO + favorable penumbra on perfusion imaging.

* Last known normal (LKN) starts the timer to when stroke patients are eligible for intervention (not to be confused with time of symptom discovery!)

* Strokes typically cause a sudden loss of function (in contrast to positive phenomena such as convulsive movements, tingling sensation, sparkling vision, which can point away from a stroke diagnosis)

* In patients with prior deficits, ask which symptoms are new or different in comparison to their baseline.

The NIHSS is widely accepted as THE stroke severity scale, and it has many strengths and some pitfalls. The NIHSS was initially developed to be used in research, and, as mentioned here, was designed to be reproducible between various groups – physicians, nurses, research staff. Higher scores correlate with bigger infarct volume. The NIHSS is not an accurate scale in that it does not necessarily capture each patient’s deficits, omitting brain functions such as gait, distal limb dexterity, and cognition. It also scores higher for dominant (L) hemispheric functions as many points depend on language function.

When screening for large vessel occlusion, remember key brain structures and functions from the L MCA, R MCA, and posterior circulation. Looking for cortical signs can be very helpful to identify larger stroke syndromes: aphasia, neglect, gaze deviation, visual field deficit.

Last but not least, keep in mind that hemorrhagic strokes (intracerebral hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage) account for about 15% of all strokes. The same screening tools for acute neurologic symptoms can be used to identify these patients, though they more often have concurrent headache or LOC than ischemic strokes (due to increased ICP and irritation from blood products). For SAH, two scales are commonly used to describe the clinical and radiographic severities: Hunt-Hess (surgical risk index) and modified Fisher scales (risk index for developing vasospasm).

Figure 1: Hunt-Hess Scale

Figure 2: Modified Fisher Scale

Fan Caprio, MD

Assistant Professor of Neurology (Stroke)

Department of Neurology

Northwestern Memorial Hospital

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Kaskar, S. Wleklinski, N. (2021, Oct 25). How to Talk Like a Neurologist. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Caprio, F]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/neuro-scores