Written by: Niki Patel, MD, MD (NUEM ‘22) Edited by: Luke Neill, MD (NUEM ‘20) Expert Commentary by: Gabby Ahlzadeh, MD

Expert Commentary

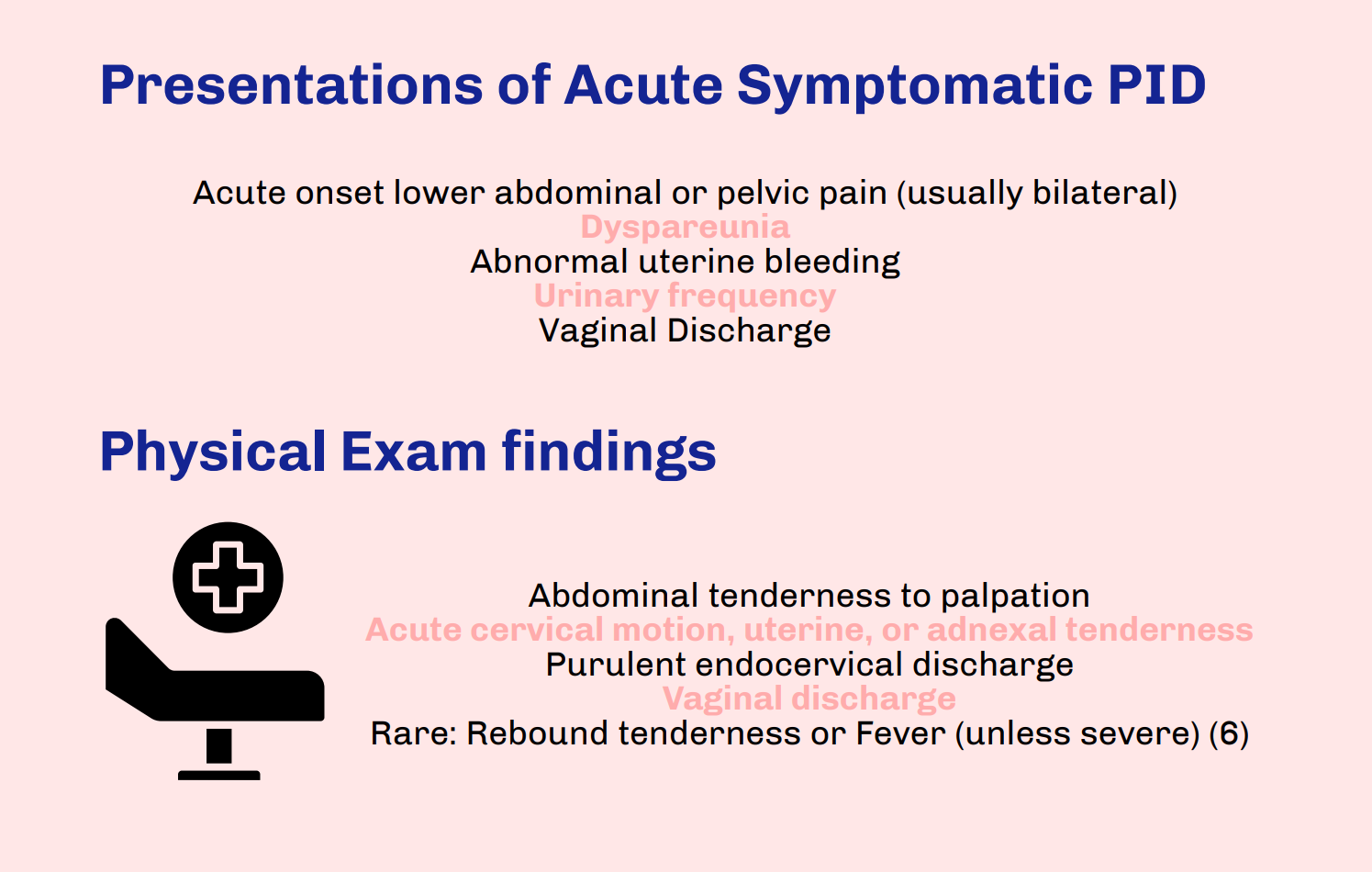

Thanks for this clear and succinct post. The differential diagnosis of lower abdominal and pelvic pain is extremely broad in both premenopausal and post-menopausal women. This is when the sexual history becomes important. A question we often overlook as part of the sexual history is asking about dyspareunia, which may help differentiate gynecological from intra-abdominal causes of abdominal pain, specifically in the case of PID.

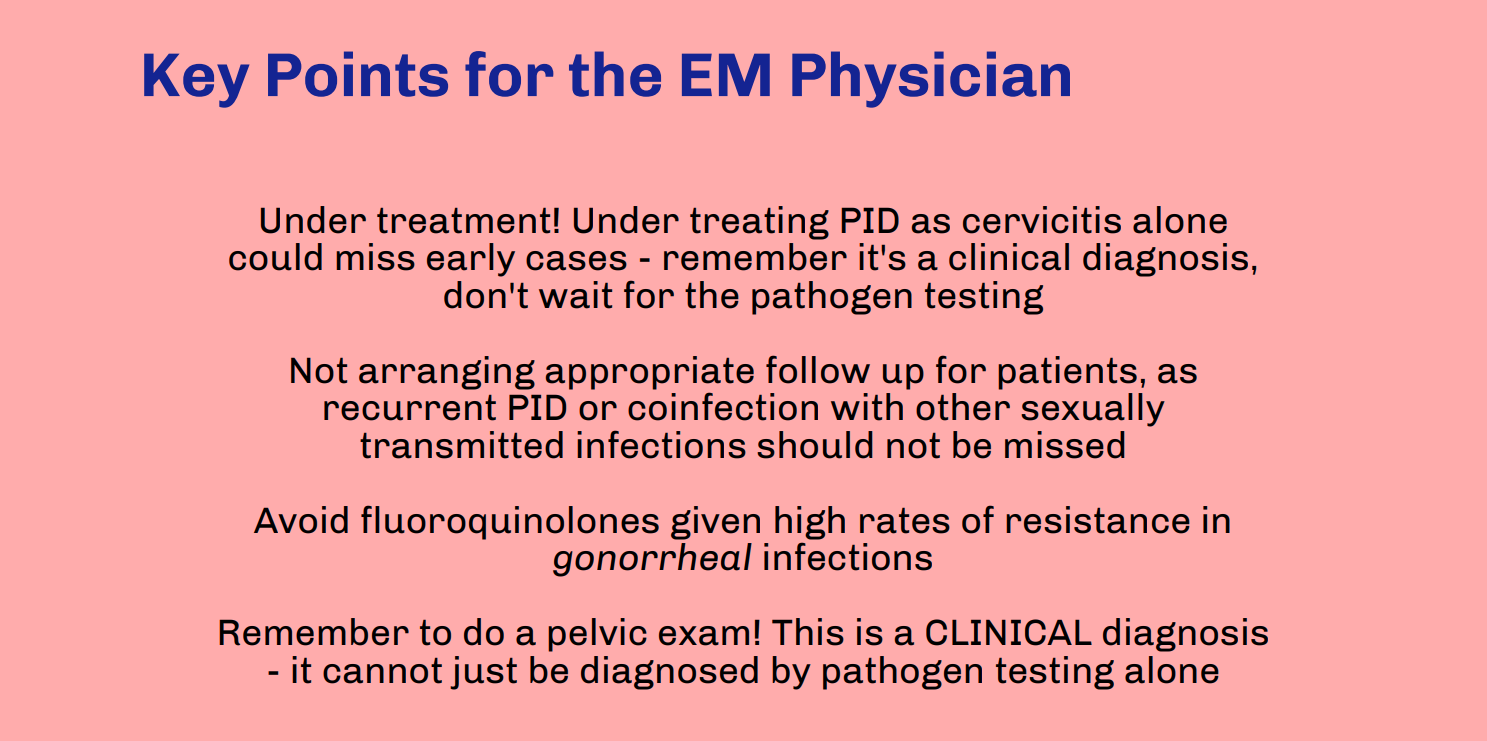

Patients with PID are frequently misdiagnosed with a urinary tract infection because they may have urinary symptoms, but the urinalysis often shows sterile pyuria, which should raise your suspicion for PID.

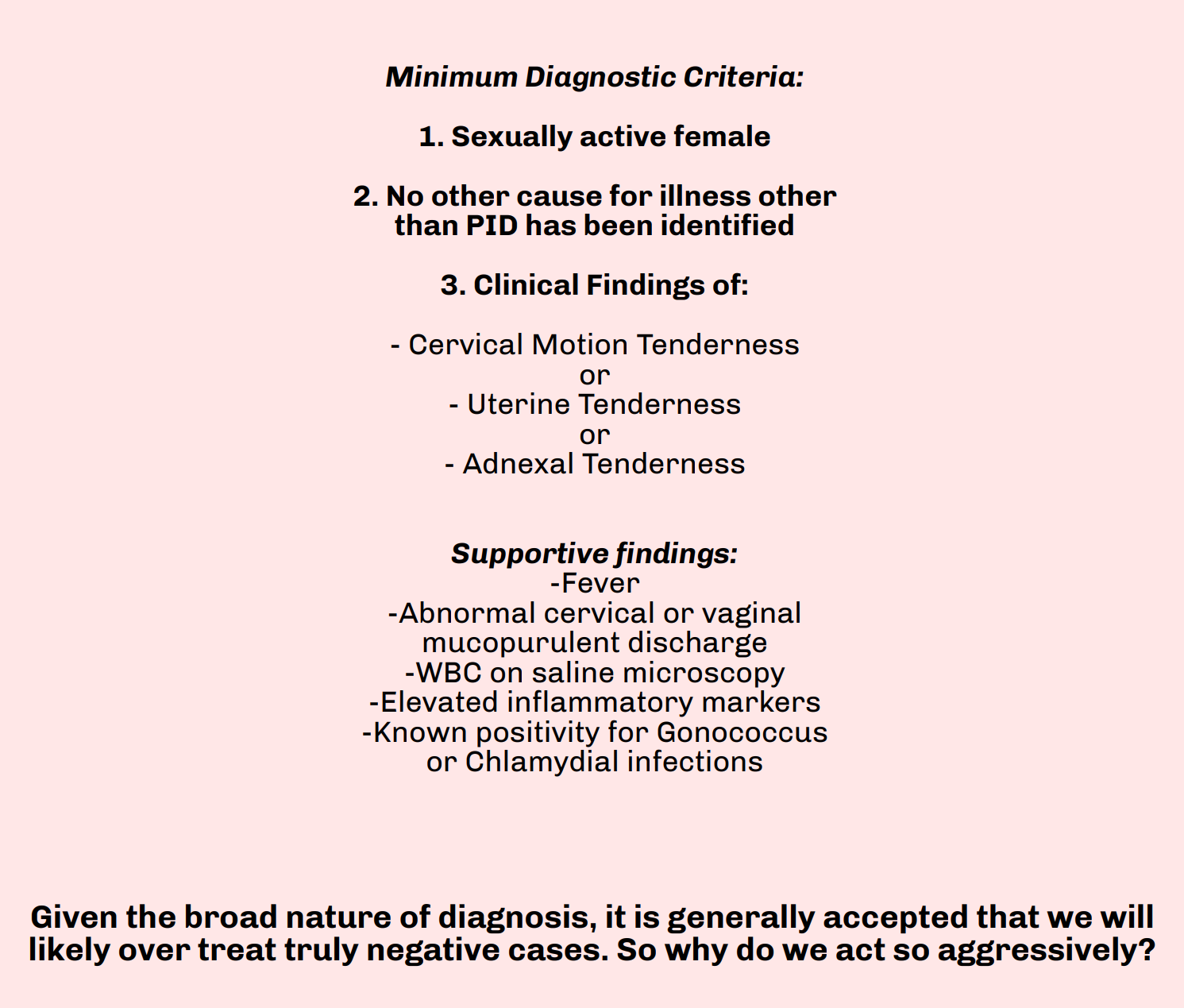

And while the utility of the pelvic exam is constantly scrutinized and questioned in patients with vaginal bleeding, it is impossible to diagnose PID without it. Having said that, the clinical diagnosis is only 65-90% specific so even minimal symptoms with no other explanation warrant antibiotic therapy to reduce further complications.

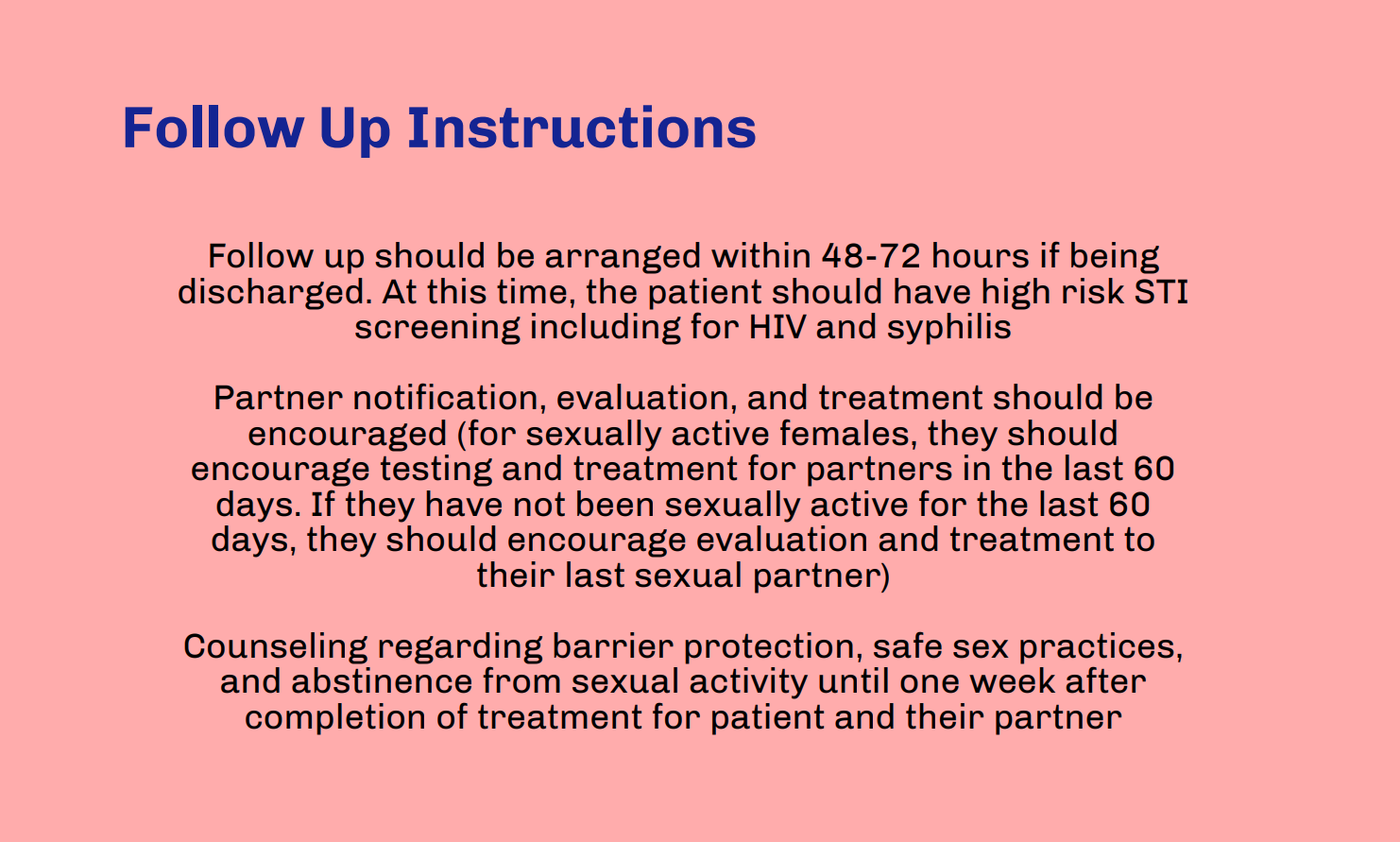

Underdiagnosis is even more significant in the adolescent patient population, who are at highest risk for developing PID. Over 70% of PID diagnoses among adolescents are made in the ED, with approximately 200,000 adolescents diagnosed annually. If the patient is accompanied by a family member or friend, having them step out to better elicit a sexual history is essential. HIV and syphilis testing should also be considered while these patients are in the ED.

Ensuring follow-up for these patients within 48-72 hours is essential and must be emphasized. Patients should understand the complications of PID and the importance of antibiotic compliance prior to discharge, especially in younger patients.

Gabrielle Ahlzadeh, MD

Clinical Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine

University of Southern California

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Patel, N. Neill, L. (2021, Apr 5). Pelvic Inflammatory Disease. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Ahlzadeh, G]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/pelvic-inflammatory-disease