Written by: Trish O’Connell, MD (PGY-2) Edited by: Jacob Stelter, MD (PGY-3) Expert commentary by: Matt Levine, MD

Expert Commentary

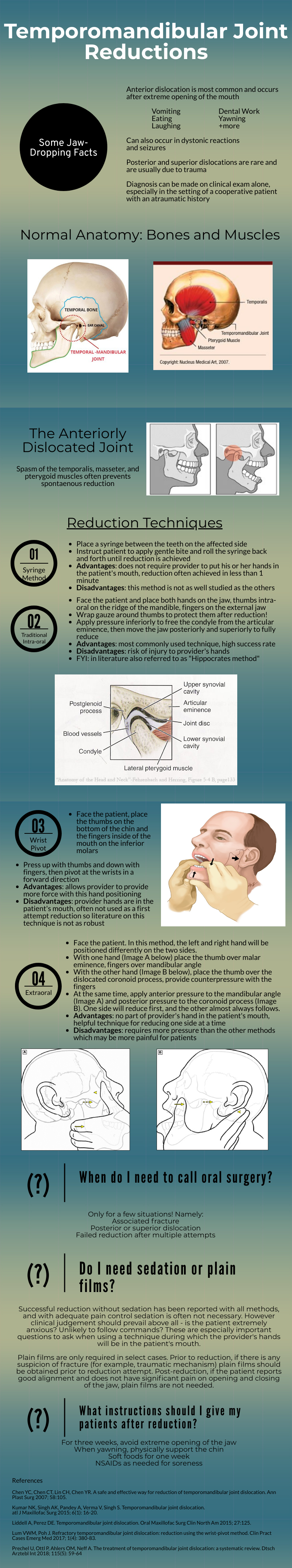

That was a high yield visual guide to TMJ reductions. Earlier in my career I was often frustrated by these cases. I was taught the traditional reduction method. I found myself having to sedate the patient and stand on the bed to generate enough downward force. This was awkward and I was still usually unsuccessful. The wrist pivot method really changed my practice. I found it required less sedation, easier to generate force without awkward positioning, required less physical strength, and led to higher success rates for me. My current practice is to have a patient roll a 10mL syringe in their mouth while I am setting up, which usually doesn’t work, and to proceed with the wrist pivot technique if still dislocated.

While procedural sedation has evolved away from versed and more towards agents such as ketamine, etomidate, and propofol, versed remains an ideal agent for TMJ reduction. It provides good anxiolysis and is a better muscle relaxant than etomidate and ketamine. The deep sedation of propofol is unnecessary.

When the sedated patient awakens, beware of “the yawn”! I’ve had patients dislocate again that way, to the chagrin of the patient (and the benefit of the procedure-seeking resident). Wrapping Kerlex gauze under the chin and around the top of the head until the patient is alert enough to avoid full yawning will prevent “the yawn.”

The main role of imaging is to rule out associated fracture. Plain films are generally inadequate to confirm or rule out TMJ dislocation. If you really need imaging, CT is the best test. If the patient had no trauma but their mouth is stuck open, you usually won’t need imaging.

Matthew R. Levine, MD

Assistant Professor

Department of Emergency Medicine

Northwestern University

How to Cite this Post

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] O’Connell, T, Stelter, J. (2020, Mar 2). Temporomandibular Joint Reductions. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Levine M]. Retrieved from https://www.nuemblog.com/blog/tmj-reduction

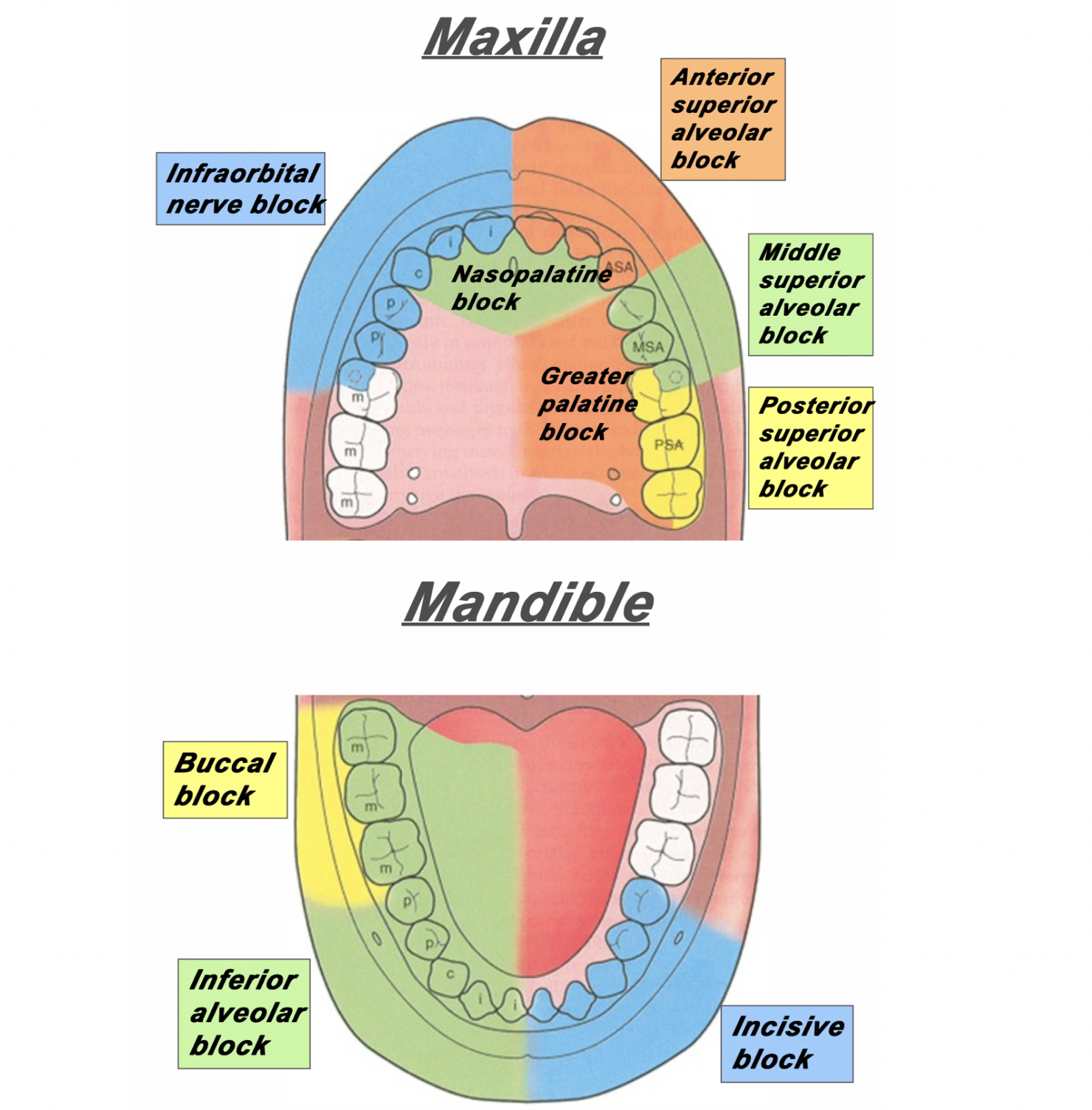

![Figure 2: For the posterior superior alveolar nerve, enter just posterior to the root of the second molar. [1]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/549b0d5fe4b031a76584e558/1579525643429-1EWBG1XTA7ZHHJ5PSYYT/PosteriorSuperiorAlveolarBlock.png)

![Figure 3: For the middle superior alveolar nerve, enter between the first molar and second premolar. [1]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/549b0d5fe4b031a76584e558/1579525901957-HQGE6VTL16IGCXYIHRTV/Screen+Shot+2020-01-20+at+7.10.54+AM.png)

![Figure 4: For the anterior superior alveolar nerve, enter just above the canine tooth. [1]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/549b0d5fe4b031a76584e558/1579527033350-0S15C2ABWP6RQIMEVBDD/AnteriorSuperiorAlveolarNerve.png)

![Figure 5: The approach and anatomy of the alveolar nerve block. [1]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/549b0d5fe4b031a76584e558/1579196433624-MHAVFNTG93XWF0PB1K45/blogpost10.png)