Written by: Nick Wleklinski, MD (NUEM ‘22) Edited by: Kumar Gandhi, MD, MPH (NUEM '20) Expert Commentary by: Scott Dresden, MD, MS

Oh How the Older Adults Fall

Introduction:

Older adults (>65yrs old) fall. In 2006, older adult patients who fell made up approximately 2.1 million of ED visits totaling $6.1 billion in health care dollars [1]. Falls are the most common cause of unintentional injury for older folks, accounting for 13% of all ED visits from 2008-2010 [2]. These numbers are only increasing as our population ages and it is predicted to double by 2030 [3]. The injuries incurred wildly vary, but these patients tend to fall into two buckets: Major injury/organic etiology à admit vs. simple mechanical fall à Discharge.

Common injuries requiring hospitalization:

Falls resulting in major injury carry significant morbidity and mortality. Hip fractures lead to deterioration in function and carry ~27% mortality at 1 year [4]. Head injuries account for a significant amount of fall-related deaths, making CT brain imagining imperative in most fall patients. Add a CT C-spine as these injuries are more common in the older adults, the Canadian and Nexus C-spine rules don’t work well for these patients [5]. Additionally, rib fractures are common and require significant analgesia to prevent splinting and subsequent complications. Be sure to consider blunt cardiac injury and pulmonary contusion! Given that falls are a frequent cause of trauma in older adult patients, it is important to keep the effects of aging in mind when running the ABC’s (Table 1) [6].

Table 1: Further considerations for ABC’s in older adult trauma patients.

The tougher scenario: Those without any injuries:

Patients without any major injuries deserve more thought than simply ruling out organic etiologies (i.e. CVA, ACS, arrythmia, etc.) and major trauma. These patients are at high risk for subsequent falls and may even have underlying physiologic injuries. Using the term “mechanical fall” is risky as it can anchor providers into comfort. Therefore, having a more regimented approach can help better risk stratify these patients.

The fall itself:

Where did it happen?

Those in nursing homes/institutional setting fall more frequently than those in the community (60% vs ~33%, respectively) [7]

Falls at home should trigger need for home safety evaluation

Have you fallen before?

History tends to repeat itself, with nearly 50% of fallers falling again within 1 year [8]

Witnessed vs Unwitnessed?

Collateral information can provide key details if a patient is a fall risk and requires further evaluation by physical therapy

How long where you on the ground? [9, 10]

Figure 1: Increased time on the ground leads to worsening fall anxiety and increased risk of rhabdomyolysis and subsequent kidney injury

Evaluating the patient:

Outside of the obvious (CVA, ACS, etc.), it is important to also consider other common etiologies:

Hypotension

Arrythmias

Infection (PNA, UTI, pressure ulcers)

Vestibular dysfunction (i.e. BPPV)

Anemia

Ask about melena as this is a commonly not investigated [11]

Delirium

Malignancy

Medications: Polypharmacy is a known issue in older adults, but there are certain medications to take note of. Antidepressants and antipsychotics are associated with the highest risk of falls while diuretics and narcotics didn’t have as much of a risk (Table 2) [12]. Additionally, who manages the meds and how are they organized at home?

Table 2: Common medications associated with falls

What is their baseline? This is the meat and potatoes of the evaluation and where future risk factors can be identified and addressed.

How steady do they feel on their feet?

Decreased cognition (Dementia, Alzheimer’s, etc.) incurs increase fall risk [13]

Do they have arthritis/chronic pain?

Can result in unsteady gait from favoring certain part of body, increasing risk

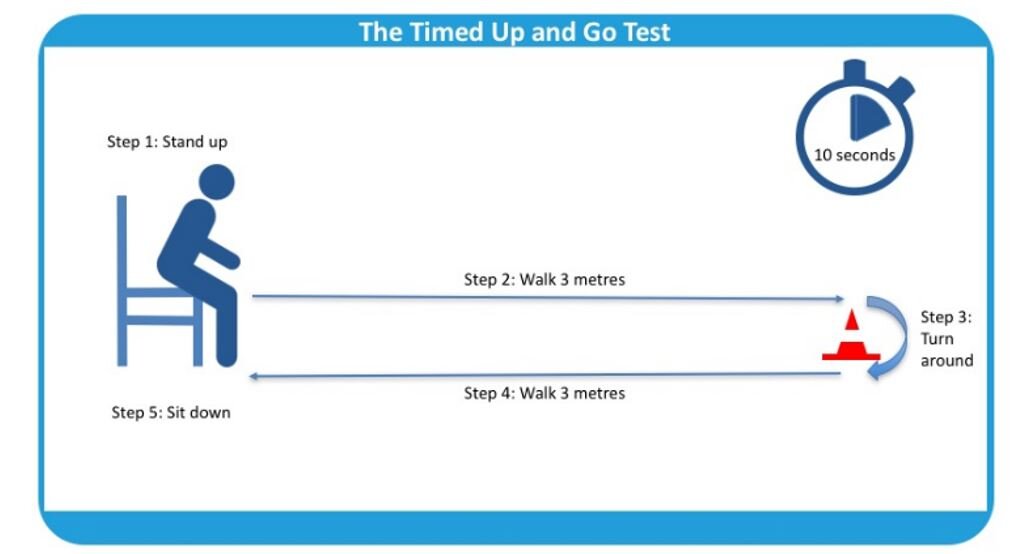

Timed Up and Go Test:

A great way to evaluate lower extremity strength and balance (figure 2)

Visual and auditory impairment: Visual acuity should be addressed. Look at their eyewear as multifocal lenses increase fall risk [14].

Feet: check for neuropathy and ask about footwear.

Assist devices used for ambulation? Do they use these devices regularly and correctly?

Delirium screening

The Confusion Assessment Method is used in triage [15]

Figure 2: The Timed Up and Go Test.

Things we can do:

Although continuity is not generally part of the EM specialty, we can help address future fall risk for these patients who we discharge after their fall evaluation. Recommending supplements such as vitamin D and calcium are helpful for reducing risk for fall-related injuries [7]. Balance training through outpatient physical therapy referrals can further help reduce fall risk. Follow up is imperative and these patients should see their PMD or a geriatrician soon after their discharge from the ER to continue their fall evaluation.

Conclusion:

While major trauma from falls is exciting and straight forward, it is important to give more thought to those older adult patients deemed to have a “mechanical fall”. Gathering information about the fall and determining the patient’s baseline can help stratify future risk. The incidence of falls is only going to increase as our population ages, so having a regimented approach to these patients is imperative.

Expert Commentary

As was expertly described, falls in older adults lead to significant morbidity and mortality. Unfortunately, in the ED they are often dismissed as “mechanical,” the injuries are treated, but the causes are never identified. The term mechanical fall is ambiguous and unhelpful and should not be used in the ED. Some mean that the fall was not a result of seizure or syncope, but it is not a clear term. Additionally, it does not help with prognosis. There are no differences in adverse events at 6 months between “mechanical” and non-mechanical faller. For a great discussion of the Myth of the Mechanical Fall see Shan Liu’s presentation at IGNITE presentation at SAEM18 (https://saem-ondemand.echo360.org/media-player.aspx/5/13/431/1608).

Even if injuries are minor, patients often do poorly. Between 36% and 50% of patients have an adverse event such as a recurrent fall, emergency department revisit, or death within 1 year after a fall, including 25% who die within 1 year. As the CDC likes to remind us, every 20 minutes someone dies from a fall (https://www.cdc.gov/steadi/index.html).

So what do we do with this medical problem that has a 25% 1-year mortality? As with many problems in geriatrics, falls are a sentinel event, and deserve a sentinel response. It is our job to prevent the next fall. The Geriatric Emergency Department Guidelines provide a framework for a risk assessment after a fall. One might think that the cause of the fall is obvious (e.g. tripped over a crack in the sidewalk). However a thoughtful assessment begins by asking “if this patient was a health 20-year-old, would he or she have fallen? “ If the answer is no, then the assessment of the underlying cause of the fall should be more comprehensive and should include a thorough history of the fall and risk factors such as ability to perform Activities of Daily Living (ADLs), appropriate footwear, and medications. Physical exam should include orthostatic blood pressure, a head to toe exam even for patients with seemingly isolated injuries, a neurologic exam with special attention to neuropathy and proximal motor strength, and a safety assessment. Patients should be able to rise from the bed or chair, turn, and steadily ambulate in the ED before considering discharge (not while the nurse is handing the patient his or her discharge paperwork). For patients who are unable to safely ambulate, consideration of an assist device such as a cane or walker should be given, physical therapy (PT) and occupational therapy (OT) consultation, and possibly hospital admission. All patients who are admitted after a fall should be admitted by PT and OT. Additionally, patients who fell should have home safety assessments which may be arranged through occupational therapy.

In addition to the GED guidelines, the CDC has developed the Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths & Injuries (STEADI) program. This program includes an algorithm for fall risk screening, assessment and intervention. For screening they recommend patients answer the Stay Independent screening (a 12 question tool), however if the patient is in the ED for a fall, this step can be omitted because the patient has already declared themselves as high risk for falls. To evaluate gait, strength, and balance, the Timed Up & Go, 30-Second Chair Stand, or 4-Stage Balance Test are recommended. In addition, to the assessments mentioned previously (medications, orthostatics), asking about potential hazards such as throw rugs or slippery floors, and a visual acuity check are advised. Once risk factors are identified they should be addressed through physical therapy, exercise of fall prevention programs, medication optimization, home safety evaluation, discussion with outpatient clinicians regarding orthostatic hypotension, referral to a podiatrist for proper footwear, recommending a vitamin D supplement. Finally, ensuring close and enduring followup is important. Consider a referral to a geriatrician if the patient doesn’t already see one.

Scott Dresden, MD, MS

Associated Professor of Emergency Medicine

Director of Geriatric Emergency Department Innovations (GEDI)

Northwestern Memorial Hospital

How To Cite This Post:

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Wleklinski, N. Gandhi, G. (2020, Nov 23). Elderly Fallers. [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Dresden, D]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/elderly-falls.

Other Posts You May Enjoy

References

Owens, P.L., et al., Emergency Department Visits for Injurious Falls among the Elderly, 2006: Statistical Brief #80, in Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. 2006, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US): Rockville (MD).

Sapiro, A.L., et al., Rapid recombination mapping for high-throughput genetic screens in Drosophila. G3 (Bethesda), 2013. 3(12): p. 2313-9.

Foundation, C.f.D.C.a.P.a.T.M.C. The State of Aging and Health in America 2007. 2007 [cited 2019.

Cenzer, I.S., et al., One-Year Mortality After Hip Fracture: Development and Validation of a Prognostic Index. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2016. 64(9): p. 1863-8.

Goode, T., et al., Evaluation of cervical spine fracture in the elderly: can we trust our physical examination? Am Surg, 2014. 80(2): p. 182-4.

Carpenter, C.R., et al., Major trauma in the older patient: Evolving trauma care beyond management of bumps and bruises. Emerg Med Australas, 2017. 29(4): p. 450-455.

Nagaraj, G., et al., Avoiding anchoring bias by moving beyond 'mechanical falls' in geriatric emergency medicine. Emerg Med Australas, 2018. 30(6): p. 843-850.

Liu, S.W., et al., Frequency of ED revisits and death among older adults after a fall. Am J Emerg Med, 2015. 33(8): p. 1012-8.

Austin, N., et al., Fear of falling in older women: a longitudinal study of incidence, persistence, and predictors. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2007. 55(10): p. 1598-603.

Deshpande, N., et al., Activity restriction induced by fear of falling and objective and subjective measures of physical function: a prospective cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2008. 56(4): p. 615-20.

Tirrell, G., et al., Evaluation of older adult patients with falls in the emergency department: discordance with national guidelines. Acad Emerg Med, 2015. 22(4): p. 461-7.

Woolcott, J.C., et al., Meta-analysis of the impact of 9 medication classes on falls in elderly persons. Arch Intern Med, 2009. 169(21): p. 1952-60.

Muir, S.W., K. Gopaul, and M.M. Montero Odasso, The role of cognitive impairment in fall risk among older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing, 2012. 41(3): p. 299-308.

Lord, S.R., J. Dayhew, and A. Howland, Multifocal glasses impair edge-contrast sensitivity and depth perception and increase the risk of falls in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2002. 50(11): p. 1760-6.

Han, J.H., et al., Diagnosing delirium in older emergency department patients: validity and reliability of the delirium triage screen and the brief confusion assessment method. Ann Emerg Med, 2013. 62(5): p. 457-465.