Written by: Sarah Sanders, MD (NUEM PGY-4) Edited by: Alison Marshall, MD (NUEM Alum ‘17) Expert commentary by: Steve Hodges, MD

Fractures of the cervical spine are injuries that must be approached with caution. Some are stable, some are unstable, and mismanagement can lead to life-altering sequelae. Remembering which fractures fit into which category is imperative for optimum emergency department care.

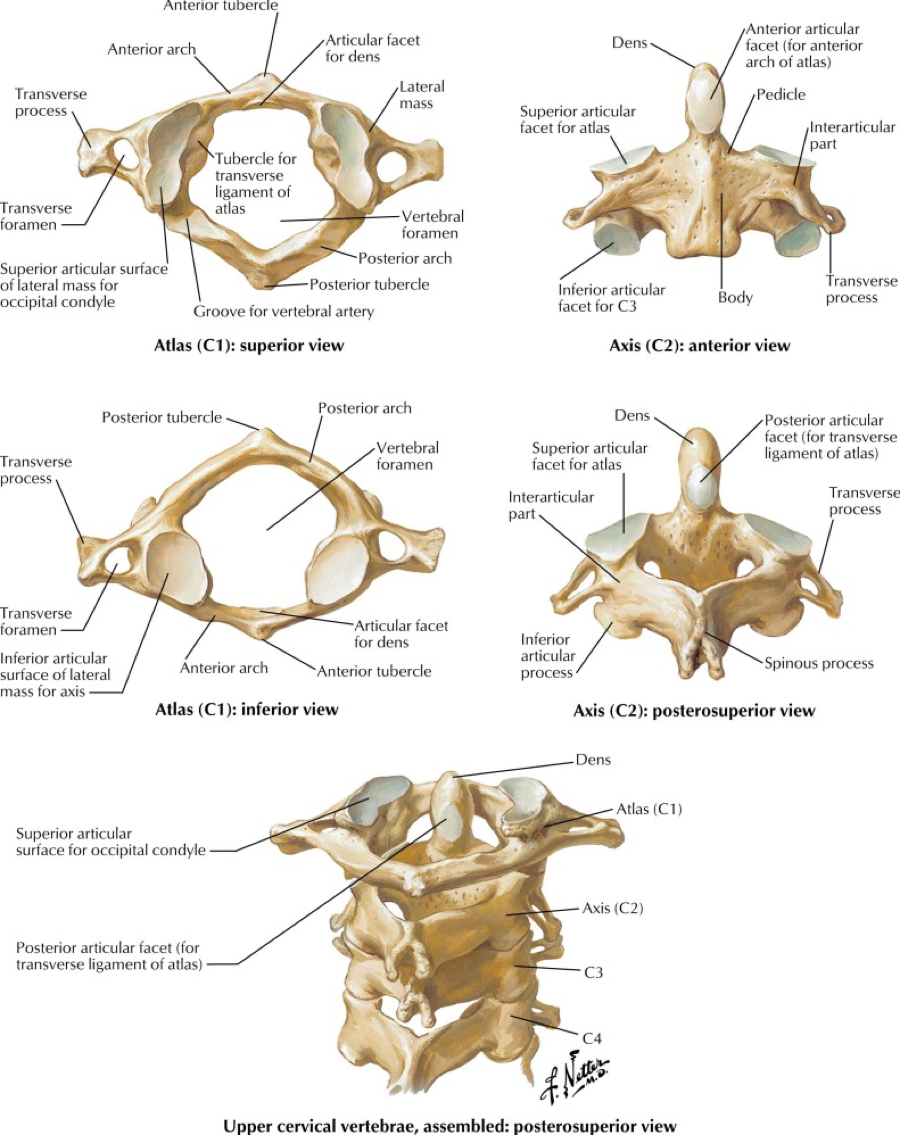

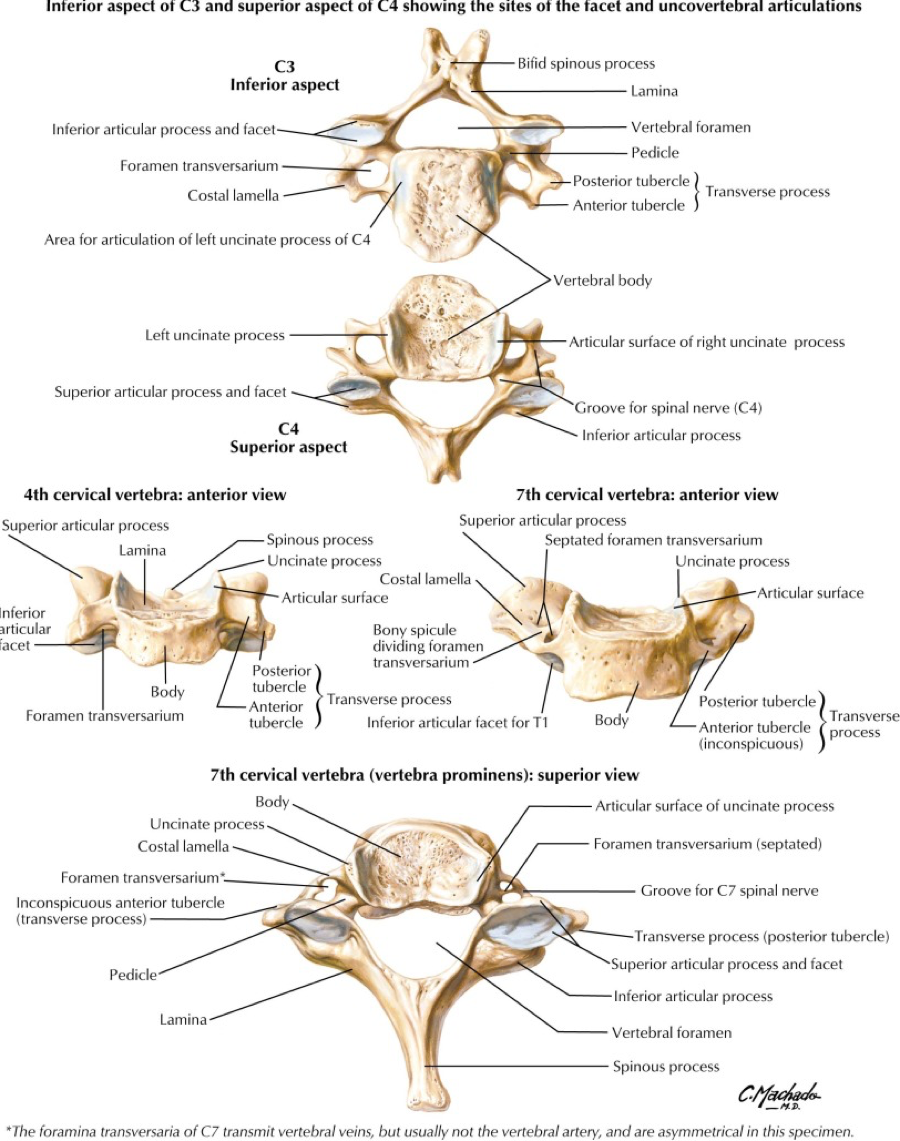

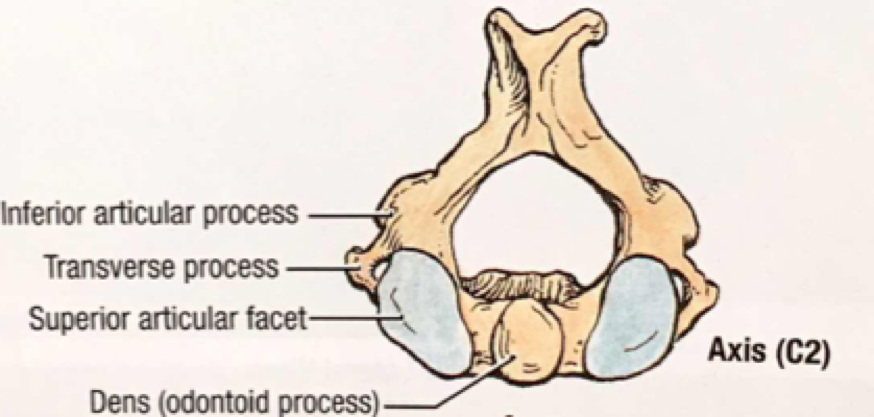

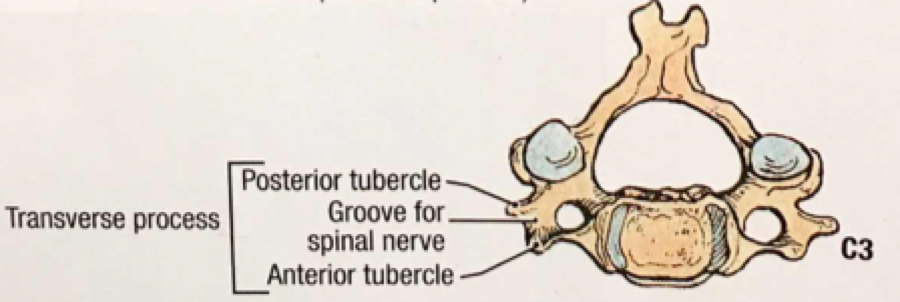

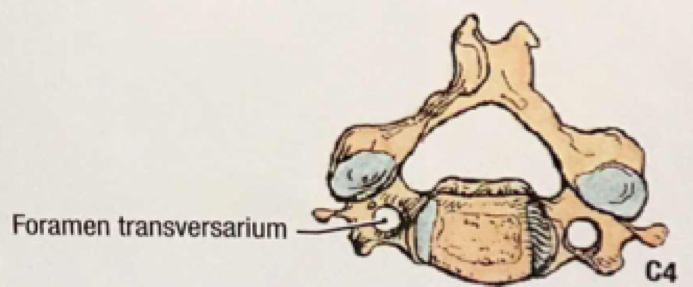

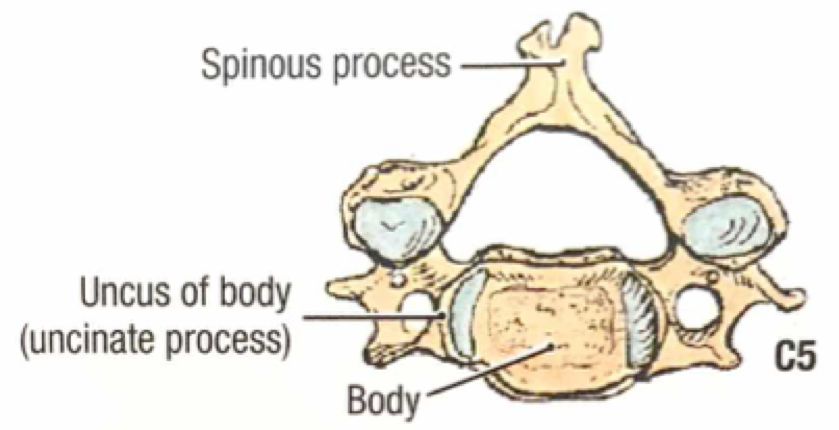

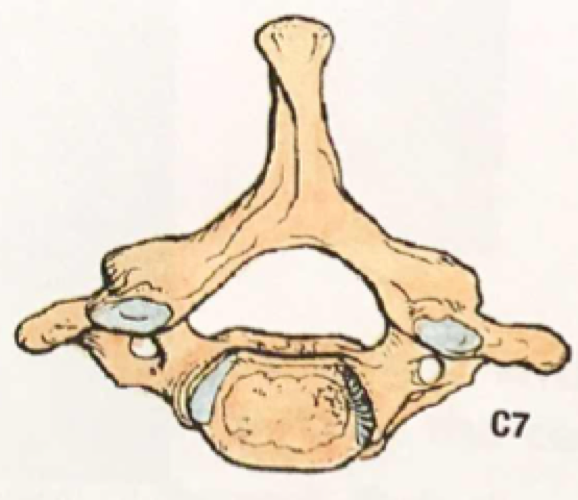

A quick review of cervical spine anatomy is a helpful starting point:

All the cervical spine anatomy images are credited to Netter, FH Atlas of Human Anatomy, Sixth Edition.

All the cervical spine anatomy diagrams are credited to Agur, AMR & Dalley, AF of Grant’s Atlas of Anatomy: Twelfth Edition.

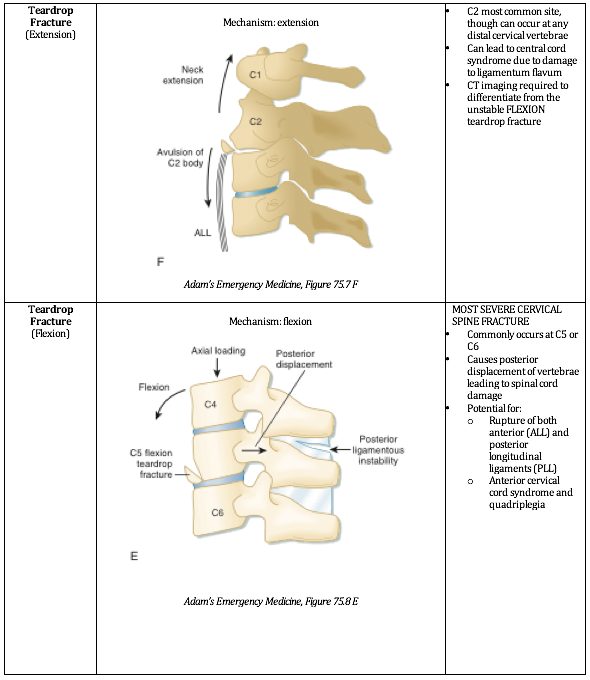

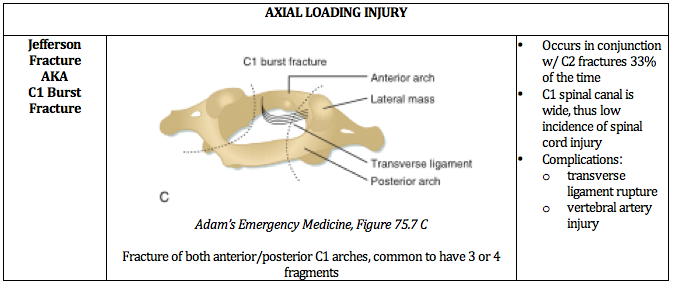

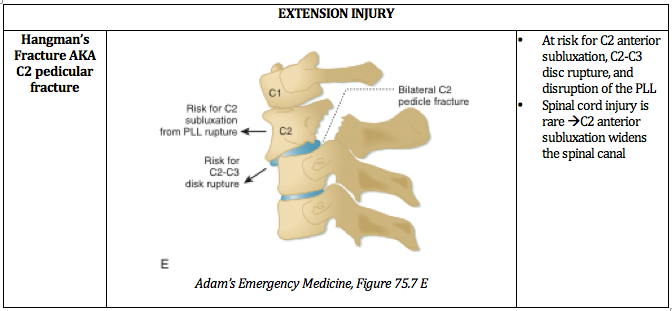

The common mnemonic “Jefferson Bit Off A Hangman’s Thumb,” is used to remember the unstable fractures, which will be reviewed in this post.

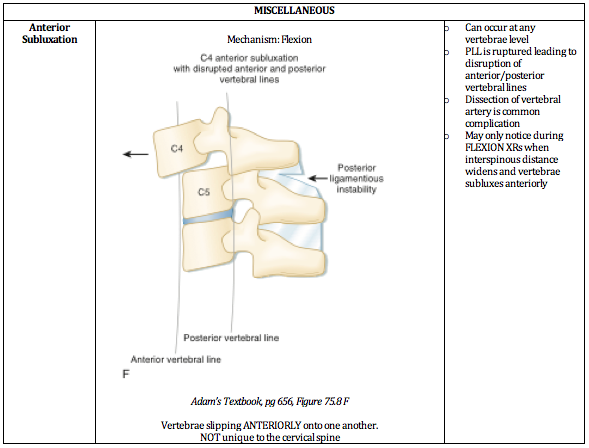

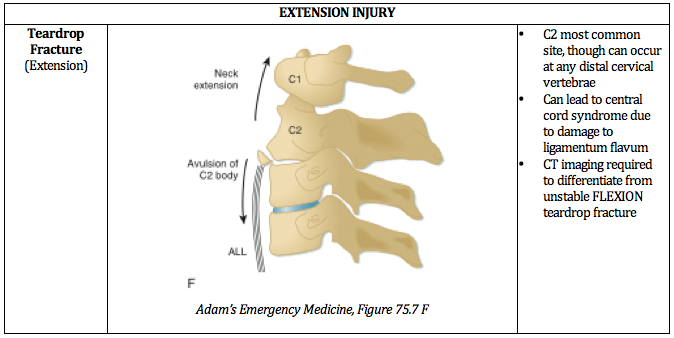

Ultimately, understanding the mechanism of injury is crucial in identifying and accurately managing these injuries. The below PV cards are organized by mechanism and tailored down to be an on-shift reference.

In conclusion, cervical spine injuries required a high index of suspicion and caution by the emergency medicine physician as their variability and potential for neurological impairment is high. Hopefully this review can provide you with additional insight and ease of memory when the next Level 1 trauma rolls through the door.

Expert Commentary

Thanks for this insightful post. You've done a really nice job in laying out the most salient points. It is important to have an understanding of the anatomy and this is a great review. Knowing the factors that put people a high risk for injury is also paramount. Certain chronic disease states and anatomic variances, as you note, do put select patient populations at risk for specific injury. The mechanism of injury is something we always talk about, but when it comes to neck trauma we need to really pay attention to all available history including paramedic reports, or even cell phone video, to get the best possible picture or the mechanism of injury. I can not stress enough the importance of a detailed neurological exam including sensation(s) and reflexes. Any asymmetric finding should raise your level of suspicion for severe injury. Moving to advanced imaging is especially important if there is a complaint of a focal neurological deficit; be that transient, subjective or blatantly obvious.

Athletes or motorcyclist who have suspected cervical spine injury, who have protective shoulder pads and/or helmets pose a unique challenge. Eventually the protective devices are going to need to be removed. There are many opinions on how best to do this and whether an x-ray should be done before attempting the removal of protective gear. From personal experience; it can be difficult to remove protective gear; I recommend getting "all hands on deck" and using an methodical slow organized approach. More recent thought is that cervical spine imaging should incorporate procedures for removal of equipment before initial radiographic evaluation.[1] Once the gear is removed a c-collar should then be applied and you can proceed with imaging.

Recommendations for imaging the cervical spine for trauma has changed quit a lot over the last several years. The National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study (NEXUS) and the Canadian C-Spine Rule (CCR) have been validated and have allowed our practice to advance such that we can effectively practice clinical medicine. However, a word of caution on using these criteria with patients who could be impaired. Sometimes the mild dementia, delirium or subtle drug, alcohol intoxication can lead us astray when we rely solely on these criteria. The cross table lateral films and specifically flexion/extension views have fallen out of favor. Most patients without focal neurological complaint or deficit are imaged with plain CT. If your patient has a focal neurological complaint or deficit, a suspected ligamentous or disc injury an MRI should be done. Depending on the exam and risk factors I would consider either a CTA or and MRA to evaluate for vascular injury.

You asked about c-collars specifically. What is available to you will be somewhat hospital - vendor specific. I prefer the Aspen or the Miami collar, they are very similar in function overall and superior to the pre-hospital EMS ones. When a patient has to be transported to another facility; make sure that the patient has full immobilization with back board and head-side blocks with the collar and head secured to the side blocks. An immobilized patient that requires intubation can make an easy air way difficult and a difficult airway terrifying. Make sure you have all your equipment prepared, including a surgical method, before you intubate. The person holding c spine immobilization needs to knows their role.....don't let go and don't move. This is the time when a video assisted intubation should be used. Use either the intubating bronchoscope or a video laryngoscope. This article talks a bit about managing airway in cervical spine injury and is a nice reference.[2]

Closing thoughts: maintain a high level of suspicion for injury in the setting of a focal neurological deficit, immobilize early immobilize often and don't be shy about intubating before transferring.

https://doi.org/10.1067/mem.2001.116333 Annals of Emergency Medicine; Baldwin et. al., "Football protective gear and cervical spine imaging" July 2001 Volume 38, Issue 1, Pages 26–30

10.4103/2229-5151.128013 International Journal of Critical Illness and Injury Science; Austin et. al., "Airway management in cervical spine injury" Jan-Mar; 4(1): 50–56

Steven W. Hodges, MD, FACEP

Assistant Medical Director

Northwestern Lake Forest Hospital

How To Cite This Post

[Peer-Reviewed, Web Publication] Sanders S, Marshall A (2019, January 21). Unstable Cervical Spine Fractures [NUEM Blog. Expert Commentary by Hodges S]. Retrieved from http://www.nuemblog.com/blog/cervical-spine-fractures.

Other Posts You May Enjoy

References

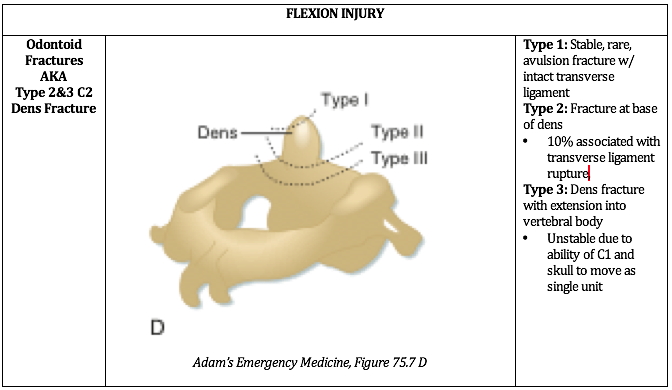

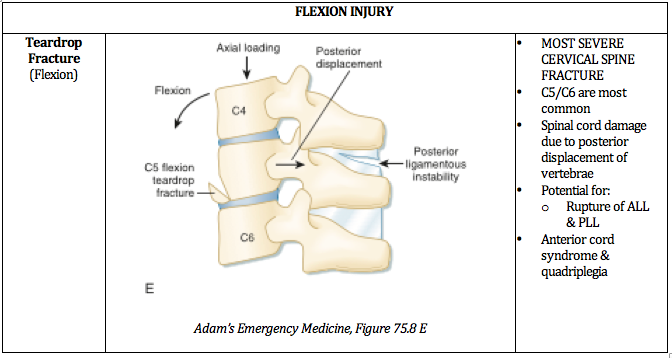

Adams, J. Lin, M. Mahadevan, SV. “Spine Trauma and Spinal Cord Injury.” Section VIII, Chapter 75. Emergency Medicine: Clinical Essentials. Second Edition. P652 - 657.

Agur, AMR; Dalley AF. Grant’s Atlas of Anatomy. Twelfth Edition. Chapter 4: Back. 2009.

Bergenheim, AT, Forssell, A. “Vertical Odontoid Fracture. Case Report.” Journal of Neurosurgery. Vol 74 (4) p665-667. 1991.

Netter, F. Atlas of Human Anatomy. Section Head & Neck. Sixth Edition. 2014.

Wheeless, CR. “Cervical Spine.” Wheeless Textbook of Orthopedics by Duke University. April 26 2016. 2 Jan 2017. http://www.wheelessonline.com/ortho/cervical_spine